Stale Incumbents Perpetuate Distrust

Low trust levels in America benefit groups like “stale incumbents,” who maintain their positions by fostering distrust and resisting change.

In a society where trust levels are low and have been falling for decades, have you ever wondered who stands to gain from this pervasive and persistent distrust?

My hypothesis is this: low trust isn’t just a social ill—it’s a profitable venture for some. Over the years, I’ve noticed different groups that seem to benefit from distrust, both within organizations and across our culture. In this post, I’ll share my observations and explore who profits from distrust. If you have your own observations or data, please share them as we delve into this critical issue together.

Adversaries

The first group that benefits from low trust is straightforward: our adversaries. Distrust and infighting often go hand in hand. It’s much easier to defeat a rival, whether in the market, in an election, in a war, or in a race for positioning, when they are busy fighting among themselves and imploding from within.

Brokers

Another group that profits from distrust are brokers. Though they often don’t have bad intentions, brokers make a living by filling the gap that distrust creates. By “broker,” I mean someone who advocates on our behalf in an untrusting or uncertain environment. This could be a real estate agent, someone who vouches for us as a business partner, a friend who sets people up on blind dates, or someone whose endorsement wins us favor with others.

Mercenaries

Mercenaries are a less well-intentioned version of brokers. These people paint a dark picture of a distrustful world and then offer to fight for us or provide protection—for a price. Mercenaries never portray themselves as such, even if that’s what they really are.

Aggregators

Aggregators are people or organizations that build a reputation for being consistently trustworthy, especially when their rivals are not. Essentially, they aggregate trust and communicate it as a symbol of value. A good example of aggregators are fast food brands. When traveling abroad, people trust an American fast food chain to be clean, consistent, and reasonably priced. Many brands across industries thrive because they’ve built a trustworthy reputation.

These groups are fairly straightforward, and many of you might find these categories intuitive and relatable. However, they didn’t seem to cover enough ground to explain the persistent low trust levels in our culture. As I thought more about it, I realized that the largest group benefiting from distrust might be hidden in plain sight…

Stale Incumbents

Now, let’s consider the largest group that might be benefiting from distrust: stale incumbents.

Imagine someone you’ve worked with who always slows down projects. They resist learning new things and believe in sticking to the old ways. They’re nice, but their team never meets deadlines or finishes projects—they always have a believable excuse. This person is a stale incumbent.

More specifically, a stale incumbent is someone in a position who is out of ideas or motivation to innovate. Their ability to keep their job depends on everyone being stuck in the status quo. Here’s how it works:

They get into a comfortable position.

They stop learning and trying new things.

They run out of ideas because they stopped learning.

They try to hide and let new ideas fade.

They allow distrust and low standards to settle in.

When new people ask questions, they blame distrust: “It’s not my fault; others aren’t cooperating.”

They make the status quo seem inevitable, doing the minimum to keep their position and discourage change.

They repeat steps 4-7.

Stale incumbents need distrust to hide behind. They want to keep their comfortable position but have no new ideas because they stopped learning. A culture of distrust is the perfect scapegoat: it can’t argue back, and people think it can’t be changed, so they stop asking questions and give up. The distrust also makes it harder for new people to show up, innovate, annd expose the stale incumbent.

Ultimately, stale incumbents can keep their jobs while delivering mediocre results. This staleness spreads, making the culture of distrust harder to reverse because more stale incumbents depend on it. It’s a cycle of mediocrity, not anger and fear.

I don’t have experimental data, but I do have decades of regular observation draw from. I believe stale incumbents help explain the persistent low trust in America. Many people started with energy but never found allies, and the stale culture assimilated them.

The good news is there’s hope. If distrust is due to stale incumbents rather than malicious actors, we may not face much resistance in bringing about change. The path to change is clear: bring in energetic people and help them bring others along. It’s hard, but not complicated. By fostering a culture of learning, innovation, and trust, we can break the cycle of mediocrity and create a more trusting and dynamic society.

My Dream: Bringing CX to State and Local Government

Bringing CX to State and Local Government would be a game-changer for everyday people.

My number one mission for my professional life is to help government organizations become high performing. If every government were high performing, I think it would change the trajectory of human history for the better in a big way.

One way to do that is to bring customer experience (CX) principles pioneered in the private sector and some forward thinking places (like the US Federal Government, the UK Government, or the Government of Estonia) and bring them to State and Local Government.

It is my dream to create CX capabilities in City and State Government in Michigan and have our state be a model for how CX can work at the State and Local level across the country.

Dreams don’t come true unless you talk about them. So I’m talking about it.

If you have the same mission or the same dream, I want to meet you. If you have friends or colleagues who have similar missions or dream, I want to meet them too. We who care about high performing, citizen-centric government want to make this happen. I want to play the role that I can play to bring CX to State and Local Government and I want to help you on your journey. Full stop.

I have so much more to say about what this could be, but I had to start somewhere. I had ChatGPT help me take some thoughts in my head and convert them into a Team Charter and a Job Description for the head of that team.

What do you think? Have you seen this? What would work? What’s missing? Maybe we can make something happen together, which is exactly why I’m putting a tiny morsel of this idea out there for those who care to react to.

The country and world are already moving to more responsive, networked, citizen-centric models of how government can work. Let’s hasten that transformation by bringing CX principles to the work our City and State Governments do every day.

I can’t wait to hear from you.

-Neil

—

Team Charter for Customer Experience (CX) Improvement in City or State Government

Purpose (Why?)

To transform and enhance the quality of government services and citizens’ daily life through CX methodologies. High impact domains include touchpoints with significant impact for the citizens who are engaged (e.g., support for impoverished families obtaining benefits) and those touchpoints affecting all citizens (e.g., tax payments, vehicular transportation), and touchpoints with high community interest.

Objectives (What Result Are We Trying to Create?)

Increase citizen satisfaction

Strengthen trust in government

Elevate the quality of life for residents, visitors, and businesses

Scope (What?)

This initiative will focus on the top 5-7 stakeholders personas driving the most value to start:

Improve how citizens experience government services, daily life, and vital community aspects

Drive change cross-functionally and at scale across interaction channels

Foster tangible improvements in the quality of life

Create and align KPIs with community priorities and establish ways to measure and communicate success

Activities (How?)

Segment residents, visitors, businesses, and identify top personas and touchpoints

Develop customer personas, journey maps, and choose highest-value problem areas to focus on for each persona

Prioritize and create an improvement roadmap

Partner with various stakeholders to drive change

Measure results, gather feedback, and align with community priorities

Share progress regularly and communicate value to stakeholders to gain momentum and support

Team and Key Stakeholders (Who?)

Leadership: A head with experience in leadership, CX methods, data, technology, innovation, and intrapreneurship

Department Liaisons: Individuals driving CX within different governmental departments

External Partners: Collaboration with other government agencies, citizen groups, foundations, the business community, and vendors

Core Team: A mix of professionals with expertise in relationship management, digital, innovation, leadership, and related fields

Timeline and Next Steps (When?)

0-6 Months: Segmentation, personas, and journey mapping

6-12 Months: Problem analysis and a prioritized roadmap creation

9-18 Months: Tangible improvements and iterative changes in focus areas

Ongoing: Continual refinement and adaptation to changing needs and priorities

—

Job Description: CX Improvement Team Leader

Position Overview:

As the CX Improvement Team Leader for City or State Government, you will drive transformative change to enhance citizens’ experience with government services and improve quality of life for citizens in this community. You will guide a cross-functional team to create innovative solutions, aligning with community priorities and creating tangible improvements in quality of life.

Responsibilities:

Lead and inspire a diverse team to achieve objectives

Create and align KPIs, establish methods for measurement

Develop and execute an improvement roadmap

Engage with stakeholders across government agencies, citizen groups, businesses, and more

Regularly share progress and communicate the value of initiatives to gain momentum and support

Collaborate with external partners and vendors as needed

Foster an innovative and responsive culture within the team

Qualifications:

Minimum of 10 years of experience in customer experience, leadership, technology, innovation, or related fields

Proven ability to drive change at scale across various channels

Strong communication and relationship management skills

Experience in government, public policy, or community engagement is preferred

A visionary leader with a passion for improving lives and a commitment to public service

Photo by NordWood Themes on Unsplash

Maximizing Organizational Performance: 7 Key Questions

Making organizations better is hard, but it doesn’t have to be complicated.

Leaders are often charged with "making the organization perform better." That's an incredibly difficult mission unless we understand what an organization, especially ours, is and how it works. Only then can we diagnose organizational problems and make improvements.

This is a pretty long, nerdy post, so here's the tl;dr for those in a hurry, and for those who need a little taste to prove the read is worth it.

If you're trying to make an organization perform better, start by asking (just) seven questions. I think you'll make sense of your biggest problems pretty quickly:

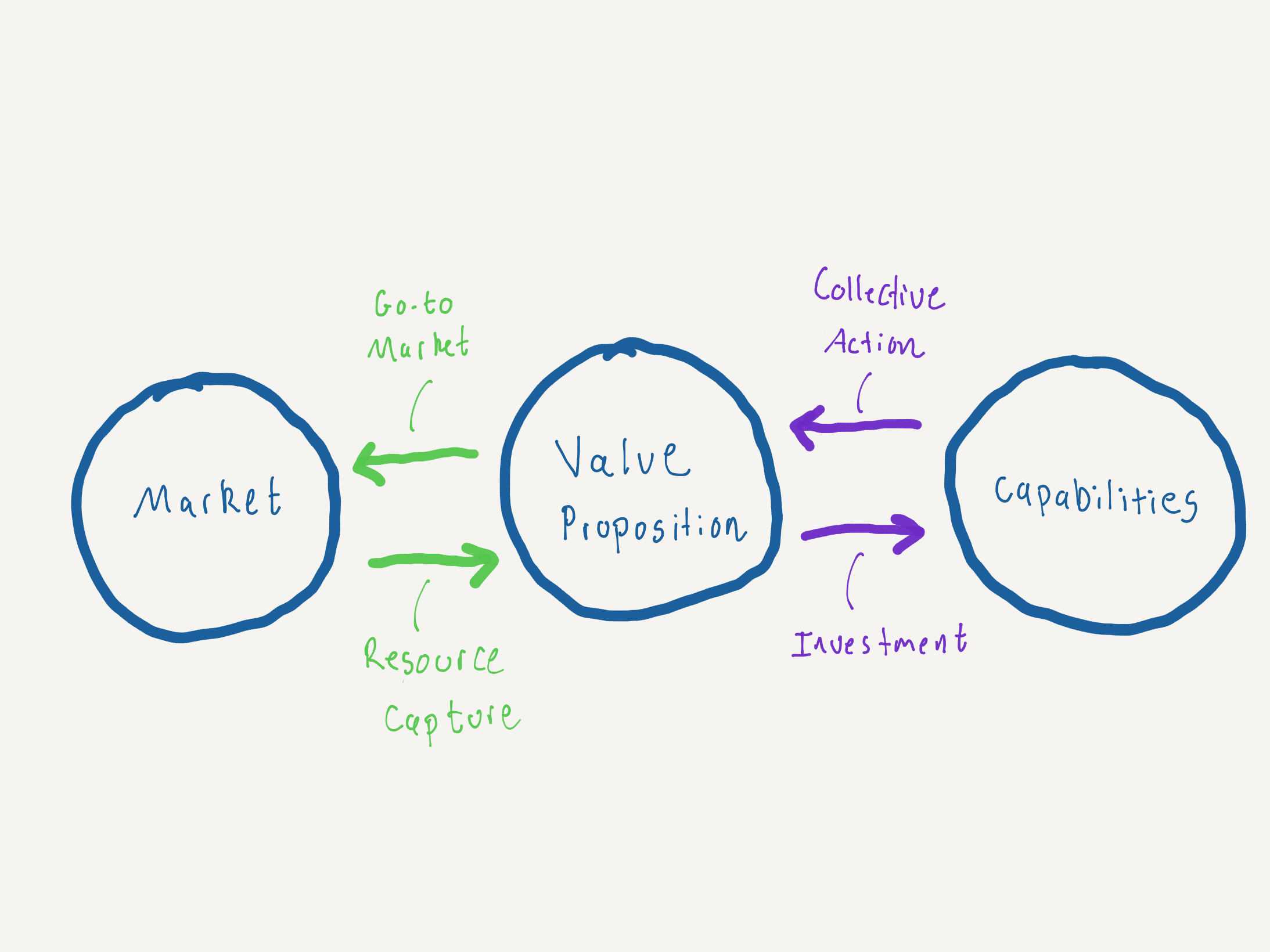

Value Proposition: What do we create that other people are willing to sacrifice something (i.e., pay) for?

Market: Who cares about what we have to offer?

Capabilities: What are the handful of things we really need to be good at to create something of value?

Go-to-Market Systems: How will we engage with our market?

Resource Capture Systems: How does the organization get the resources it needs?

Collective Action Systems: How will we work together to turn our capabilities into something of value?

Investment Systems: How will we develop the capabilities that matter most?

Making organizations better is hard, but it doesn't have to be complicated.

Leaders are often charged to “make the organization perform better”. That’s an incredibly difficult mission unless we understand what an organizations, especially ours, is and how it works. Only then can we diagnose organizational problems and make improvements.

This is a pretty long, nerdy, post so here’s the tl;dr for those in a hurry, and for those that need a little taste to prove the read is worth it.

If you’re trying to make understand and organization and help it perform better, start with asking (just) seven questions. I think you’ll make sense of your biggest problems pretty quickly:

Value Proposition: What do we create that other people are willing to sacrifice something (i.e., pay) for?

Market: Who cares about what we have to offer?

Capabilities: What are the handful of things we really need to be good at to create something of value?

Go-to-Market Systems: How will we engage with our market?

Resource Capture Systems: How does the organization get the resources it needs?

Collective Action Systems: How will we work together to turn our capabilities into something of value?

Investment Systems: How will fwe develop the capabilities that matter most?

Making organizations better is hard, but it doesn’t have to be complicated.

The Seven-Part Model of Organizations

So, what is an organization?

I'd propose that an organization, at its simplest, is only made up of seven components:

Value Proposition

Market

Capabilities

Go-to-Market Systems

Resource Capture Systems

Collective Action Systems

Investment Systems

If we can understand these seven things about an organization, we can understand how it works and consequently make it perform better. There are certainly other models and frameworks for understanding organizations (e.g., McKinsey 7-S, Business Model Canvas, Afuah Business Model Innovation Framework) which serve specific purposes - and I do like those.

This seven-part model of organizations is the best I've been able to produce which maintains simplicity while still having broad explanatory power for any organization, not just businesses. Each component of the model answers an important question that an organization leader should understand.

The seven parts (Detail)

The first three parts of the model are what I think of as the outputs - they're the core foundation of what an organization is: a Value Proposition, a Market, and a set of Capabilities.

Value Proposition: What do we create that other people are willing to sacrifice something (i.e., pay) for?

The Value Proposition is the core of an organization. What do they produce or achieve? What is the good or the service? What makes them unique and different relative to other alternatives? This is the bedrock from which everything else can be understood. Why? Because the Value Prop is where the internal and external view of the organization come together - it's where the rubber meets the road.

It's worth noting that every stakeholder of the organization has to be satisfied by the Value Proposition if they are to engage with the organization: customers, constituents, shareholders, funders, donors, employees, suppliers, communities, etc.

Market: Who cares about what we have to offer?

Understanding the Market is also core to an organization because any organization needs to find product-market fit to survive. This question really has two subcomponents to understand: who the people are and what job they need to be done or need that they have that they're willing to sacrifice for.

It's not just businesses that need to clearly understand their Markets - governments, non-profits, and even families need to understand their Market. Why? Because no organization has unlimited resources, and if the Value Proposition doesn't match the Market the organization is trying to serve, the organization won't be able to convince the Market to part with resources that the organization needs to survive - whether that's sales, time, donations, tax revenues, or in the case of a family, love and attention from family members.

Capabilities: What are the handful of things we really need to be good at to create something of value?

Thus far, we've talked about what business nerd types call "product-market fit," which really takes the view that the way to understand an organization is to look at how it relates to its external environment.

But there's also another school of thought that believes a firm is best understood from the inside out - which is where Capabilities come in.

Capabilities are the stuff that the organization has or is able to do which they need to be able to produce their Value Proposition. These could be things like intellectual property or knowledge, skills, brand equity, technologies, or information.

Of course, not all Capabilities are created equal. When I talk about Capabilities, I'm probably closer to what the legendary CK Prahalad describes as "core competence." Let's assume our organization is a shoe manufacturer. Some of the most important Capabilities probably are things like designing shoes, recruiting brand ambassadors, and manufacturing and shipping cheaply.

The shoe company probably also has to do things like buy pens and pencils - so sure, buying office supplies is a Capability of the firm, but it's not a core Capability to its Value Proposition of producing shoes. When I say "Capabilities," I'm talking about the "core" stuff that's essential for delivering the Value Proposition.

Finally, we can think of how Capabilities interact with the Value Proposition as an analog to product-market fit, let's call it "product-capability fit." Aligning the organization with its external environment is just as important as aligning it to its internal environment.

When all three core outputs - Value Proposition, Market, and Capabilities - are in sync, that's when an organization can really perform and do something quite special.

In addition to the three core outputs, Organizations also have systems to actually do things. These are the last four components of the model. I think of it like the four things that make up an organization's "operating system."

Go-to-Market Systems: How will we engage with our Market?

How an organization "goes to market" is a core part of how an organization operates. Because after all, if the product or service never meets the Market, no value can ever be exchanged. The Market never gets the value it needs, and the organization never gets the resources it needs. A good framework for this is the classic marketing framework called the 4Ps: Price, Product, Place, and Promotion.

But this part of the organization's "operating system" need not be derived from private sector practice. Governments, nonprofits, faith-based organizations, and others all have a system for engaging with their Market; they might just call it something like "service delivery model," "logic model," "engagement model," or something else similar.

The key to remember here is that go-to-market systems are not how parties within the organization work together; it's how the organization engages with its Market.

Resource Capture Systems: How will the organization get the resources it needs?

Just like a plant or an animal, organizations need resources to survive. But instead of things like food, sunlight, water, and oxygen, and carbon dioxide, organizations need things like money, materials, talent, user feedback, information, attention, and more.

So if you're an organizational leader, it's critical to understand what resources the organization needs most, and having a solid plan to get them. Maybe it's a sales process or levying of a tax. Maybe it's donations and fundraising. Maybe for resources like talent, it's employer branding or a culture that makes people want to work for the organization.

This list of examples isn't meant to be comprehensive, of course. The point is that organizations need lots of resources (not just money) and should have a solid plan for securing the most important resources they need.

Collective Action Systems: How will we work together to turn our capabilities into something of value?

Teamwork makes the dream work, right? I'd argue that's even an understatement. The third aspect of the organization's operating system is collective action.

This includes things like operations, organization structure, objective setting, project management approaches, and other common topics that fall into the realm of management, leadership, and "culture."

But I think it's more comprehensive than this - concepts like mission, purpose, and values, decision chartering, strategic communications, to name a few, are of growing importance and fall into the broad realm of collective action, too.

Why? Two reasons: 1) organizations need to move faster and therefore need people to make decisions without asking permission from their manager, and, 2) organizations increasingly have to work with an entire network of partners across many different platforms to produce their Value Proposition. These less-common aspects of an organization's collective action systems help especially with these challenges born of agility.

So all in all, it's essential to understand how an organization takes all its Capabilities and works as a collective to deliver its Value Proposition - and it's much deeper than just what's on an org chart or process map.

Investment Systems: How do we develop the capabilities that matter most?

It's obvious to say this, but the world changes. The Market changes. Expectations of talent change. Lots of things change, all the time. And as a result, our organizations need to adapt themselves to survive - again, just like Darwin's finches.

But what does that really mean? What it means more specifically is that over time the Capabilities an organization needs to deliver its Value Proposition to its Market changes over time. And as we all know, enhanced Capabilities don't grow on trees - it takes work and investment, of time, effort, money, and more.

That's where the final aspect of an organization's operating system comes in - the organization needs systems to figure out what Capabilities they need and then develop them. In a business, this could mean things like "capital allocation," "leadership development," "operations improvement," or "technology deployment."

But the need for Investment Systems applies broadly across the organizational world, too, not just companies.

As parents, for example, my wife and I realized that we needed to invest in our Capabilities to help our son, who was having a hard time with feelings and emotional control. We had never needed this "capability" before - our "market" had changed, and our Value Proposition as parents wasn't cutting it anymore.

So we read a ton of material from Dr. Becky and started working with a child and family-focused therapist. We put in the time and money to enhance our "capabilities" as a family organization - and it worked.

Again, because the world changes, all organizations need systems to invest in themselves to improve their capabilities.

My Pitch for Why This Matters

At the end of the day, most of us don't need or even want fancy frameworks. We want and need something that works.

I wanted to share this framework because this is what I'm starting to use as a practitioner - and it's helped me make sense of lots of organizations I've been involved with, from the company I work for to my family.

If you're someone - in any type of organization, large or small - I hope you find this very simple set of seven questions to help your organization perform better.

Making organizations better is hard, but it doesn't have to be complicated.

The potential of Government CX to improve social trust

Government CX is a huge opportunity that we should pursue.

Several times last week, while traveling in India, people cut in front of my family in line. And not slyly or apologetically, but gratuitously and completely obliviously, as if no norms around queuing even exist.

In this way, India reminds me of New York City. There are oodles and oodles of people, that seem to all behave aggressively - trying to get their needs met, elbowing and jockey their way through if they need to. It’s exhausting and it frays my Midwestern nerves, but I must admit that it’s rational: it’s a dog eat dog world out there, so eat or be eaten.

What I realized this trip, is that even after a few days I found myself meshing into the culture. Contrary to other trips to India, I now have children to protect. After just days, I began to armor up, ready to elbow and jockey if needed. I felt like a different person, more like a “papa bear” than merely a “papa”. like a local perhaps.

I even growled a papa bear growl - very much unlike my normal disposition. Bo, our oldest, had to go to the bathroom on our flight home so I took him. We waited in line, patiently, for the two folks ahead of us to complete their business. Then as soon as we were up, a man who joined the line a few minutes after us just moved toward the bathroom as if we had never been there waiting ahead of him

Then the papa bear in me kicked in. This is what transpired in Hindi, translated below. My tone was definitely not warm and friendly:

Me: Sir, we were here first weren’t we?

Man: I have to go to the bathroom.

Me: [I gesture toward my son and give an exasperated look]. So does he.

And then I just shuffled Bo and I into the bathroom. Elbow dropped.

But this protective instinct came at a cost. Usually, in public, I’m observant of others, ready to smile, show courteousness, and navigate through space kindly and warmly. But all the energy and attention I spent armoring up, after just days in India, left me no mind-space to think about others.

This chap who tried to cut us in line, maybe he had a stomach problem. Maybe he had been waiting to venture to the lavatory until an elderly lady sitting next to him awoke from a nap. I have no idea, because I didn’t ask or even consider the fact that this man may have had good intentions - I just assumed he was trying to selfishly cut in line.

Reflecting on this throughout the rest of the 15 hour plane ride, it clicked that this toy example of social trust that took place in the queue of an airplane bathroom reflects a broader pattern of behavior. Social distrust can have a vicious cycle:

Someone acts aggressively toward me

I feel distrust in strangers and start to armor up so that I don’t get screwed and steamrolled in public interactions

I spend less time thinking about, listening to, and observing the needs of others around me

I act even more aggressively towards strangers in public interactions, because I’m thinking less about others

And now, I’ve ratcheted up the distrust, ever so slightly, but tangibly.

The natural response to this ratcheting of social distrust is to create more rules, regulations, and centralize power in institutions. The idea being, of course, that institutions can mediate day to day interactions between people so the ratcheting of social distrust has some guardrails put upon it. When social norms can’t regulate behavior, authority steps in.

The problem with institutional power, of course, is that it’s corruptible and undermines human agency and freedom. Ratcheting up institutional power has tradeoffs of its own.

—

Later during our journey home, we were waiting in another line. This time we were in a queue for processing at US Customs and Border patrol. This time, I witnessed something completely different.

A couple was coming through the line and they asked us:

Couple: Our connecting flight is boarding right now. I’m so sorry to ask this, but is it okay if we go ahead of you in line?

Us: Of course, we have much more time before our connecting flight boards. Go ahead.

Couple: [Proceeds ahead, and makes the same request to the party ahead of us].

Party ahead of us: Sorry, we’re in the same boat - our flight is boarding now. So we can’t let you cut ahead.

Couple: Okay, we totally understand.

The first interaction in line at the airplane bathroom made me feel like everyone out there was unreasonable and selfish. It undermined the trust I had in strangers.

This interaction in the customs line had the opposite effect, it left me hopeful and more trusting in strangers because everyone involved behaved considerately and reasonably.

First, the couple acknowledged the existence of a social norm and were sincerely sorry for asking us to cut the line. We were happy to break the norm since we were unaffected by a delay of an extra three minutes. And finally, when the couple ahead said no, they abided by the norm.

We were all observing, listening, and trying to help each other the best we could. In my head, I was relieved and I thought, “thank goodness not everyone’s an a**hole.

It seems to me that just as there’s a cycle that perpetuates distrust, there is also a cycle which perpetuates trust:

Listen and seek to understand others around you

Do something kind that helps them out without being self-destructive of your own needs

The person you were kind toward feels higher trust in strangers because of your kindness

The person you were kind to can now armor down ever so slightly and can listen for and observe the needs of others

And now, instead of a ratchet of distrust, we have a ratchet of more trust. Instead of being exhausting like distrust, this increase in trust is relieving and energy creating.

—

At the end of the day, I want to live in a free and trusting society. If there was to be one metric that I’m trying to bend the trajectory on in my vocational life - it’s trust. I want to live in a world that’s more trusting.

This desire to increase trust in society is why I care so much about applying customer experience practices to Government. Government can disrupt the cycle of distrust and start the flywheel of trust in a big way - and not just between citizens and government but across broader culture and society.

Imagine this: a government agency, say the National Parks Service, listens to its constituents and redesigns its digital experience. Now more and more people feel excited about visiting a National Park and are more able to easily book reservations and be prepared for a great trip into one of our nation’s natural treasures.

So now, park visitors have more trust in the National Park Service going into their trip and are more receptive to safety alerts and preservation requests from Park Rangers. This leads to a better trip for the visitor, a better ability for Rangers to maintain the park, and a higher likelihood of referral by visitors who have a great trip. This generates new visitors and adds momentum to the flywheel.

I’m a dataset of one, but this is exactly what happened for me and my family when we’ve interacted with the National Parks’ Service new digital experience. And there’s even some data from Bill Eggers and Deloitte that is consistent with this anecdote: CX is a strong predictor of citizens’ trust in government.

And now imagine if this sort of flywheel of trust took place across every single interaction we had with local, state, and federal government. Imagine the mental load, tension, and exhaustion that would be averted and the positive affect that might replace it.

It could be truly transformational, not just with what we believe about government, but what we believe about the trustworthiness of other citizens we interact with in public settings. If we believe our democratic government - by the people and for the people - is trustworthy, that will likely help us believe that “the people” themselves are also more trustworthy. After all, Government does shape more of our. daily interactions than probably any other institution, but Government also has an outsized role in mediating our interactions with others.

Government CX is a huge opportunity that we should pursue, not only because of the improvement to delivery of government service or the improvement of trust in government. Improvement to government CX at the local, state, and federal levels could also have spillover effects which increase social trust overall. No institution has the reach and intimate relationship with people to start the flywheel of trust like customer-centric government could, at least that I can see.

Photo by George Stackpole on Unsplash

Measuring the American Dream

If you set the top 15 metrics, that the country committed to for several decades, what would they be?

In America, during elections, we talk a lot about policies. Which candidate is for this or against that, and so on.

But policies are not a vision for a country. Policies are tools for achieving the dream, not the American Dream itself. Policies are means, not ends.

I’m desperate for political leaders at every level - neighborhood, city, county, state, country, planet - to articulate a vision, a vivid description of the sort of community they want to create, rather than merely describing a set of policies during elections.

This is hard. I know because I’ve tried. Even at the neighborhood level, the level where I engage in politics, it’s hard to articulate a vision for what we want the neighborhood to look like, feel like, and be like 10-15 years from now.

Ideally, political leaders could describe this vision and what a typical day in the community would be like in excruciating detail, like a great novelist sets the scene at the beginning of a book to make the reader feel like they’ve transported into the text.

What are you envisioning an average Monday to be like in 2053? I need to feel it in my bones.

Admittedly, this is really hard. So what’s an alternative?

Metrics.

I’m a big fan of metrics to help run enterprises, because choosing what to measure makes teams get specific about their dreams and what they’re willing to sacrifice.

Imagine if the Congress and the White House came up with a non-partisan set of metrics that we were going to set targets for and measure progress against for decades at a time? That would provide the beginnings of a common vision across party, geography, and agency that everyone could focus on relentlessly.

This is the sort of government management I want, so I took a shot at it. If I was a player in setting the vision for the country, this would be a pretty close set of my top 15 metrics to measure and commit to making progress on as a country.

This was a challenging exercise, here are a few interesting learnings:

It’s hard to pick just 15. But it creates a lot of clarity. Setting a limit forces real talk and hard choices.

It pays to to be clever. If you go to narrow, you don’t have spillover effects. It’s more impactful to pick metrics that if solved, would have lots of other externalities and problems that would be solved along the way. For example, if we committed to reducing gun deaths, we’d necessarily have to make an impact in other areas, such as: community relationships, trust with law enforcement, healthcare costs, and access to mental health services.

You have to think about everybody. Making tough choices on metrics for everyone, makes the architect think about our common issues, needs, and dreams. It’s an exercise that can’t be finished unless it’s inclusive.

You have to think BIG. Metrics that are too narrow, are more easily hijacked by special interests. Metrics that are big, hairy, and audacious make it more difficult to politicize the metric and the target.

Setting up a scorecard, with current state measures and future targets would be a transformative exercise to do at any level of government: from neighborhood to state to nation to planet.

It’s not so important whether my metrics are “right” or if yours are, per se. What matters is we co-create the metrics and are committed to them.

Let’s do it.