The Thief of Joy

In a world wired for comparison, I’m learning that joy isn’t found by avoiding it—but by choosing to start with presence.

One of my colleagues often reminds our team that “comparison is the thief of joy.” He’s right.

At work, we compare the software fixes we actually delivered versus the ideal. I compare myself to more professionally successful friends. I compare my tantrumming toddler to a calmer child—or even to a calmer version of himself. I may compare one colleague to a so-called “higher performer,” whatever that means.

A common kind of comparison many of us make—one that still steals from us—is comparing ourselves to someone less fortunate. “Appreciate the dinner you have; there are kids all over the world who are starving,” we might say to our picky-eating kids. But even this steals something—maybe our humanity—because to make the comparison, we must place ourselves above someone else.

All these comparisons steal joy.

But just as comparison is the thief of joy, it’s also the propellant of progress. To improve, comparison can be a useful tool and powerful motivator. We make change when we measure where we are against where we want to be or a competitor. Companies do this with financial statements. Patients do it with weight and body fat percentage. Our whole society is engineered to compare—and that leads to progress.

So we are in a bind, because two things at odds are true: comparison is the thief of joy, and also the propellant of progress.

Even if would rather it be otherwise, my brain is rigorously trained—yours may be too—to compare. I need a replacement behavior when I catch myself comparing. I can’t just “not compare.” I need to do something else instead.

It seems to me that the replacement behavior to train myself in is simply observing. Paying attention to what’s here, soaking it in, being present, meditating, noticing. These are all flavors of the same root behavior: observation.

We’re forced to compare our youngest son’s height and weight because he has been underweight his entire first year of life. I’m constantly fighting the urge to compare his milestones—crawling, sitting, teething—to children without Down syndrome. With him, the thief of joy is always near.

But so is the opportunity to observe and find joy. Griffin has a spark in his smile I can’t explain. He pulls me into observing him—soaking in the gift of who he is every time I see him. He is truly magnetic. And even though it’s so easy to slip into comparison with him, the joy he brings to my heart feels limitless. Because when I’m with him, I am fully there. Fully appreciating. Fully observing.

To me, this act—of observing long enough to outlast the temptation of comparison—feels like an act of defiance. That joy with Griffin feels like the most hard earned of all the joy we have in our lives. It is as much an act of desperation as it is an act of triumph.

I raise him skyward when I need to get back to the moment I am in. When I lift him above my head—he starts to lift his legs, and he smiles and giggles. And then I smile. And then I remember: he’s here. There is something to celebrate exactly in what he is. There is something unique and special in this lad. I don’t have to travel in my mind to an alternate time or an alternate universe where Griffin’s life wouldn’t be as hard as I know it’s going to be.

There is joy. Right here. Right now.

The way out of this bind is in the order of operations. We may not be able to function without comparison, but we can choose when we do it. The key is to start with observation. We can begin by soaking in what we have—by noticing assets and having gratitude. Then, after we’ve practiced observation, sure—we can compare.

So before I compare my kid to their calmer friend, I can observe their humor and sense of wonder. Before I compare my job to an easier one I could have, I can observe the chance I have to make a difference alongside amazing colleagues. I can observe the joy that’s already here—before I compare my life to what it could have been.

Comparison may be the thief of joy. But we can experience joy before we even open the door to that conniving thief.

My colleague reminded us that comparison is the thief of joy earlier this week because we had a software release. And at first, it ate at me. Because deep down, I have known this for a long time, but have been helpless to stop it. I know comparison steals my joy—and I’ve known it since I was a kid, when adults would compare me to other kids and the comparison would burn my childhood innocence.

But now, after reflecting more, I feel agency. And we should feel agency, rather than seeing comparison as an inevitability. Because even if we fall into the trap of comparison, we don’t have to start with it.

Time Isn’t Just Precious. It’s Freedom.

If someone else dictates of the rhythm of the day, they control us.

If you want to dominate someone—really dominate them—control their clock.

Not just how many hours they have, but the rhythm of their life. Interrupt their mornings. Hijack their focus. Scramble their sense of flow. Make their time unpredictable, reactive, chaotic. Do that long enough, and they’ll lose track of themselves.

This isn’t advice. It’s a warning.

Because this is happening to us. Every day.

We talk about money as a form of power—and it is. But we rarely talk about time that way. And we should. Because time is where character is built. How we use it shapes who we become—for better or worse.

When someone else controls our time, they start shaping our character.

Some people respect our time. They show up when they say they will. They ask for our attention instead of grabbing it. They give us room to say no. Others? They drop things on us last minute, run meetings long, change plans on a whim, manufacture urgency. They don’t just steal our time—they steal our pace. And some of them know exactly what they’re doing.

This can be casual. It can be unconscious. Or it can be a form of deliberate mind control.

Either way, it’s on us to protect ourselves. After a few months of having a newborn mixed with a toxic news cycle, I finally realized what was happening—and that we can choose differently. Here’s how I’ve started to do that.

First, set your default rhythm.

Pre-block the calendar for deep work. Guard time for meals. Protect a few slow moments in the day. We need to build our rhythm before the bids on our time roll in. Otherwise, we’ll only ever react to the world.

Second, audit your rhythm-breakers.

This was the big one for me.

Who or what is constantly pulling you out of flow? It’s worth naming them—because once we name them, we can decide what kind of access they deserve.

Here’s my list right now:

• Me (when I don’t protect my own time)

• My wife

• My kids

• Work—especially senior leaders

• Soccer practice

• The weather and seasons

• My dog

• My kids’ school

• Illness

• Bills

• Entertainers and influencers

• Marketers and advertisers

• Telemarketers

• Sports broadcasts

• Political actors, speeches, and announcements

• My dietary choices

• Appointments (doctors, dentists, shops, government agencies)

Some of these we choose. Some we don’t. Some we want to give more access to—others, we need firmer boundaries with. But the act of reflecting, listing, noticing? That’s the first defense. Rhythm starts with awareness.

I’m fine having my time hijacked by a kid who wants to kick a soccer ball after dinner. I’m not fine giving that same access to a blustering politician or a LinkedIn influencer trying to amp me up about salary and status. One interruption builds relationship. The other creates chaos and anxiety. That difference matters.

Because this isn’t just time management. Our character is at stake.

In Character by Choice, I explored how character isn’t built in the big, heroic moments—it’s built in the margins. In the pauses. In the slowness of ordinary life. That’s where curiosity, love, and listening grow. That’s where we cultivate goodness.

But if we’re always hurried and hijacked, we don’t get to those margins. We don’t reflect. We don’t hear. We don’t connect. We just react.

Seedlings don’t grow well when sunshine and water are erratic and unpredictable. Neither do we.

This might sound like a small thing. Saying no. Blocking time. Holding a rhythm. But I don’t think it is.

It’s a lever. A quiet one. But powerful.

Because time is where character is built. If someone else owns our time, they start to control our intention. And if our days are always frantic and fractured, the kindest parts of us—the curious, generous, loving parts—are suppressed.

So here’s a suggested first step: take an honest look at your rhythm. Who controls your clock? Who deserves to? And what boundaries—loving, firm, deliberate—do you need to put in place to protect the part of you that’s trying to be good?

That’s the work ahead for us. It’s small. But it’s sacred.

Why I'm a Part-Time Capitalist

We can choose which game we want to play.

I’ve come to the conclusion that I want to be a part-time capitalist.

What I mean by this is that I want to create enough material wealth for my family and society to live a good life, but I don’t want capitalism to dominate my identity or values. I want to earn a living, but my goal in life isn’t to be a good producer or consumer. I’ll engage with capitalism where it serves me—maybe the equivalent of two days a week—but I won’t live and breathe it as though it’s my religion.

This realization didn’t come to me overnight. It simmered for years, as I wrestled with the game society handed me: capitalism. From an early age, we’re taught to measure success by wealth, status, and accumulation. For a long time, I felt like I was failing at it—even though my family and I were doing just fine. Capitalism has a way of making you feel like nothing is ever enough. It whispers that you’re not climbing the ladder fast enough, not maximizing your earnings the way you could.

But at some point, I started to ask myself: Why am I even playing this game? What if I don’t want to “win” capitalism? What if I’d rather play a different game altogether?

That’s where my sons come in. They love soccer. They play with an abandon and joy that makes me envious. Watching them, I realized they’ve found a game that suits them—one they’ve chosen for themselves. Soccer has creativity, fluidity, and rhythm. It’s nothing like football, the sport I played for years growing up.

I chose football because that’s what my friends were doing. As a Michigander, it felt natural to play, and I enjoyed being part of a team. But looking back, I see that it didn’t suit me. I wasn’t built for it—physically or mentally. It was someone else’s game, and I just happened to be good enough at it to get by.

That’s how capitalism has felt for me as an adult: the default game I got pulled into. Like football, it has its virtues. It provides structure and can even be exhilarating at times. But it’s not the primary model for how I want to live.

I’m never going to “win” at capitalism, and I don’t want to. I’m not willing to make the sacrifices required to maximize my earnings or climb higher, because I value other things more. I love being a father. I’m drawn to public service. I care about relationships, creativity, and dignity far more than accumulation.

For years, though, I struggled under capitalism’s invisible grip. People told me I had talent and potential, which I heard as: You could be doing more. This latent anxiety followed me everywhere. Could I provide enough for my family? Could I live up to everyone’s expectations? That sense of “not enough” became like a chronic cold I couldn’t quite shake.

But then came my a-ha moment: I don’t have to play this game—not fully, anyway. I realized I could be a subscriber to capitalism part-time and play my own game for the rest of my life.

For me, this shift has been about aligning my life with my values. It’s why I’ve embraced a nonlinear career, oscillating between government and corporate roles to find balance. It’s why Robyn and I have crafted a marriage that works for us, breaking free from traditional gender roles. She works a flexible schedule, and I’ve leaned into an unconventional path as a husband and father. We’ve structured our lives around fairness and teamwork rather than default societal expectations.

It’s also why we’ve chosen to raise our family in the city instead of a suburb. The city challenges us, inspires us, and aligns with the cultural and inter-religious values we’re navigating as a couple. Every one of these decisions reflects a conscious choice to reject the "default game" and build something that works for us.

This path isn’t easy. Freedom is exhilarating, but it’s also daunting. Choosing your own game requires courage. It means setting boundaries, risking judgment, and often swimming upstream. That means being willing to be a little weird or out on a ledge, at least some of the time.

But it’s worth it. Recently, I’ve started to feel the effects of this mindset as I’ve entered a new job. Do I have to be the best at work and think about it constantly? No. Do we need an excess of money to complete every home renovation we want this year? No. Do I need to loudly reject capitalism or evangelize my alternative path? No. I’ve chosen my line in the sand, and I’m okay with where it puts me.

While I wish I’d started sooner, I’m grateful to be starting now. Better late than never.

So here’s my question for you: What’s the game you’ve been playing? Is it one you chose, or was it handed to you? What would it look like to redefine the rules and build a life that fits you?

The process isn’t easy. It’s challenging, peculiar, and sometimes lonely. But it’s also liberating. It’s your life, after all—why not make the rules yourself?

The Irony of Intention: My Accidental Phone Fast

The problem isn’t that my phone is distracting, it’s that my intentions are weak.

The Unintended Experiment

Just like everyone else, I spend many bullshit hours on my phone every week and a few more loathing myself for it. I know it affects my mood, my body, and my relationships negatively. It’s terrible, and such a waste of time and energy. Every week, I tell myself, “this is the week” and yet, I do it again. It’s maddening.

Oddly, I forgot my phone at the office on Thursday. I didn’t think the two hour round trip was worth it to retrieve it, which meant I would be without a phone until Tuesday - my next in-office day. This created a natural experiment: what happens when I literally can’t be on my phone because it’s not here? All the usual tropes were true…I can get by without it, I’m so less distracted, I sleep better, social media is so addictive, yadda yadda yadda.

But there was one big surprise. I used to blame my phone and social media for all these distractions and toxic influences. But really, it’s not the phone or social media that’s the problem - it’s that my intentions are weak.

A strong intention is an intention that you care about enough to follow through, even if it requires substantial discomfort. For me, running and exercising is a strong intention. A weak intention is an intention that fizzles away even under minor duress. Mowing the lawn and raking the leaves is one of those for me. I’ve been saying I’m going to do it for weeks, but here I am and another weekend has passed without it happening. That’s a weak intention.

I realized this weekend that my phone is not really a distraction, it’s just the easiest thing to do when I’m not exactly sure what I want to be doing. The problem, really, is that within the ebbs and flows of the day, I don’t really have intentions of how I want things to go. And when I don’t have a clear, strong intention I don’t sit idle - I bullshit.

Because when I bullshit, I can feel comfortable and feel like I’m doing something useful, without having to go through the struggle of figuring out something better and actually doing it. It’s a perfect trap.

The real solution isn’t limiting the phone, it’s forming stronger intentions for the part of the day I’m in. If I had stronger intentions, I wouldn’t be on my phone as much because I’d be spending my time doing things I care more about.

The Parallel: Resisting Yummy Bacon

Here’s another way to think about it, let’s talk about bacon.

I like bacon. It’s really delicious. When I smell it, I still crave it. Same thing with pepperoni and chicken wings. They’re SO good.

But I haven’t eaten those foods in years, I went solidly pescetarian about 10 years ago and haven’t looked back. I don’t even eat much fish anymore. Even when there’s delicious bacon, pepperoni, or chicken wings on a restaurant menu I don’t flinch any more. Why? Because I feel much stronger of an intention about not eating meat than I used to. Now, I have a strong intention because I’ve decided that I don’t want to take an animal’s life to avoid starvation if I don’t have to, especially because there are many delicious alternatives that are better for my health and the environment.

In high school, I used to waffle because I didn’t really have strong intentions about vegetarianism - I kind of just flirted with it and was a vegetarian when it was convenient, more than anything else. So I caved and flip-flopped on my dietary restrictions often.

My phone is the same way, because I don’t have a strong intention of what I want to do or focus on today, I jump to my phone because it’s an easy mechanism to give myself something to do.

The Rub: Making Intention Tangible

I will get my phone from the office when I head in on Tuesday. But this experiment has taught me a valuable lesson, it’s important to make short-term, intra-day intentions strong and explicit. Luckily, I do this already for longer time horizons of my life:

What do I intend to contribute to that’s bigger than just me?

I’m good on this one. I intend to be a loving husband, father, and citizen. Beyond unconditional love to my family, I want to help the world become a free and trusting place.

What do I intend for this phase of my life?

I’m good on this one too, but it’s a bit more scattered.

Right now, I intend to help our family take root, form a cohesive bond, and be ready to flourish once we’re out of diapers. Professionally, I intend to do a lot of experiments to understand the different paths I can take to influence the things I care about most: trust in government, social trust, morality and character, leadership on every block, and issues like homicide, suicide, parks, and the literacy rate.

What do I intend for this season within this phase?

I don’t think about this a ton, but I think about it enough.

I intend to help get our home life running efficiently and with less friction. I also intend to get back to connecting with friends and our extended family. Finally, I intend to bring energy to my teams at work and figure out where I want to pivot. Oh, and publish this book I’ve been working on for seven years.

This is where I get stuck. I get caught up in the motions and don’t translate these longer-term and loftier intentions into our daily grind.

What do intend for the next week or two?

Generally, I wouldn’t think like this. But if I took the time to , I would probably say, “Get our lingering house projects and yardwork done before the holidays hit. Take more time to have fun and make eye contact with my sons. Go on a date with Robyn. Get my edits done so I can hire a proofreader and cover designer for this book project.”

What do I intend for this part of the day (i.e., between now and our next meal)?

Generally, I wouldn’t think like this. But if I took the time for it, I’d say - get the minimum cleaning done so we can take a family walk and play a game together.

Because I don’t get specific at this granular, intra-day level, and set an explicit intention for the next few hours before I eat the next meal, I bullshit. Usually on my phone.

If I don’t set specific intentions for the immediate few hours, It’s like my brain says, “I don’t know exactly what comes next. Do I want to make a plan that’s in line with my favorite hobbies and long-term plans? Do I want to make the most of my workday afternoon? Uhhh, naw. I’ll just look at videos of college kids doing trick shots with golf balls bouncing off of cookware and check my e-mail instead.”

The Takeaway: Intention in the Immediate

This is the big lesson. We have to have clear, strong intentions for the long-term but also for the time that’s right in front of our face. This is true at home, in our work, and in our community organizations. Some people are good at setting longer-term intentions. Others are better at setting immediate, short-term, intentions. But the truth is, we really need strong intentions for both.

If we don’t set clear intentions, especially at the level of the next few hours, we bullshit. And for me that usually means bullshitting on my phone.

But it could manifest as something more subtle than scrolling on a smartphone. At home, it could be cleaning stuff I don’t really have to clean, or just turning on the TV in the background while I wash dishes - both are comfortable, but aren’t in line my strongest intentions.

At work, it could be attending useless meetings to feel busy without actually having to work, or doing mundane tasks which nobody cares too much about - both are comfortable, but they’re usually not what the best use of our time is.

All in all, I’m really glad I forgot my phone at the office for a weekend. It was good to have a reason to reflect on it. My test will be to set stronger intra-day intentions so I bullshit less and pay attention to my family more. I don’t have to be addicted to my phone, none of us do. If we take the time to set clear intentions in the immediate-term that ladder up to our longest-term intentions, we can minimize our bullshit hours and spend that time doing things we really love, things that really matter, and things to connect with the people we care about deeply.

Coaching Requires Dedicated, intensely Focused Time

The biggest error of coaching - not being intentional about it - can be avoided by dedicating real time to it.

People develop faster when they are coached well, but coaching doesn’t happen without intent. To be a better coach, start with making actual “coaching time” that is intentional and intensely focused.

First, as a manager, we must dedicate one-to-one time with whomever we are trying to coach. 30 minutes per week, used well, is enough.

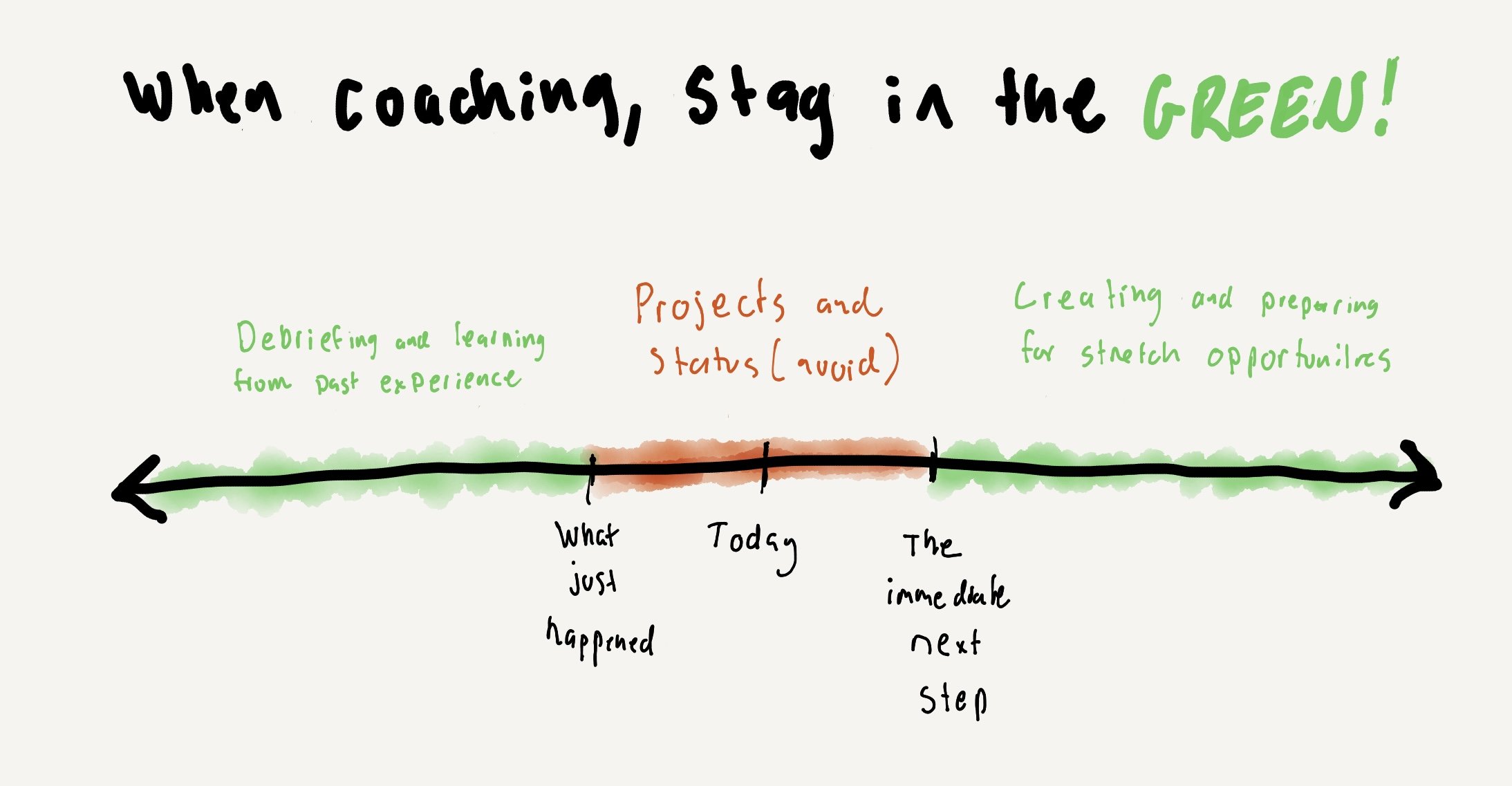

Second, that time can’t be about projects or status. It has to be spent on debriefing to glean learnings from past performance, or on how to create and prepare for future stretch opportunities.

Find a better way to manage status and project work than during a 1-1 and dedicate that time too and use it with intense focus. Personally, I like daily stand-ups from Agile/Scrum methodology and a once weekly full project review with the whole team.

Then, set a rule that during the dedicated time you will not talk about project status or the daily grind of work. If you dedicate time and hold firm to that rule, you’ll end up having a productive coaching conversation. Here are four questions that I’ve found work well to structure a 30-minute coaching conversation.

On a scale of 1 to 100, what percent of the impact you think you could be making are you actually making? (2-4 minutes)

Compared to last week, is your rate of growth accelerating, decelerating, or about the same? (2-4 minutes)

What do you want to talk about? (20-25 minutes)

What’s something I can do to help you feel respected and supported? (2-4 minutes)

This concept applies broadly: whether it’s coaching our team at work, our kids, our students, a volunteer group we’re part of, or co-coaching our marriage together with our partner, we must dedicate and focus the time. In my experience, the results of that dedicated time are exponential after just a few weeks.