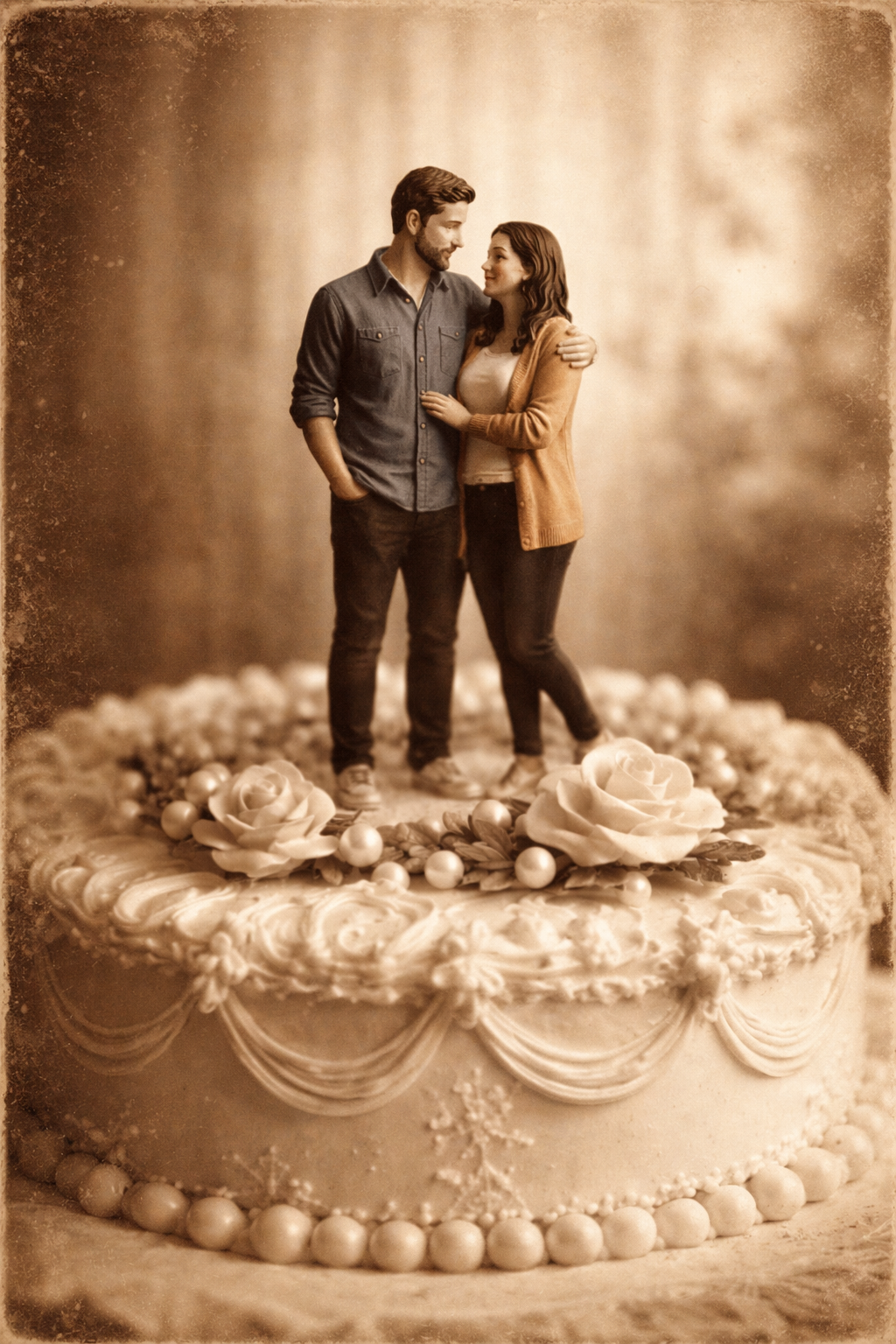

Life’s biggest decision: who you marry

Holding down a job is only a small part of a successful marriage.

Let’s stop pretending the biggest decision in life is what college you go to or what job you land. The real make-or-break decision? Who you marry.

In our family, this isn’t just a saying—it’s a foundational belief. Marriage isn’t one big day. It’s a lifelong choice that shapes your character, your children, your capacity to thrive, and your joy.

That means preparing our kids to answer four questions—really well:

Can they be a good spouse?

Do they act with integrity, love unconditionally, and make real sacrifices when it counts?Can they choose a good partner?

Do they know how to recognize integrity, unconditional love, and sacrificial character in someone else?Can they build a strong marriage?

When adversity hits, will they turn toward their partner instead of away—and grow stronger together?Can they support a family?

Can they generate enough income to meet their needs—and live with humble tastes, rather than chase status or excess?

Our entire education system is built around Question #4—economic self-sufficiency. Ironically, I’d argue it’s the least important trait when it comes to marrying well. So for the most important decision of their lives, our kids are left to learn from us, extended family, or maybe their friends—if they’re lucky.

That means the real curriculum—the one that actually shapes their future—is what we model and teach at home:

Things like integrity, love, and sacrifice. Like courage. Also self-awareness, discernment, communication, understanding, and leadership.

And yes—literacy. Because reading is how they’ll keep teaching themselves long after we’re done.

We do our kids a disservice in America because we act like holding down a job is the most important thing a person should be prepared to do. It’s not.

Believing that sells life short—and discounts the value of love, meaning, and human connection.

What we emphasize in America misses the point and leaves our kids unprepared to make the most important decision of their lives well.

A Mantra For Those Who Feel Squeezed

The only way this totally squeezed life works is if we help each other.

I think I’m at least 80% accepting of the fact, finally, that I won’t be a wealthy man. We’re blessed, and affluent by most standards, but our base budget is certainly humbled by the fact that we have four kids.

And this tension—between feeling like we’re making it but still feeling stretched—also exists with our time.

We show up for our kids and help out our family, friends, and neighbors as much as we can. But we also always feel like we’re drowning—the laundry, dishes, and daily grind are never stable. Despite the fact that we’d admit we’re doing our best and doing a decent job, it never feels like enough.

And despite all this, I still feel so much selfish guilt.

I don’t serve anyone in need whom I don’t already know, in any meaningful way, though my faith and my own moral sensibility demand it. I have let down friends—all the time, lately—it takes me months to call someone back or set up lunch, catch up over drinks, or deliver a meal to help out friends who are new parents.

We are part of the squeezed middle—we’re not living month to month with our money or time—but we don’t have enough time or money to easily trade one for the other. We’re squeezed.

And I don’t mean this as a “middle class” issue, per se, because there are plenty of families wealthier and poorer than ours, both in time and money, who feel squeezed. From investment bankers to blue-collar workers, I know families across the spectrum who feel this same pressure.

The squeezed are a surprisingly large cohort who feel stuck because they can’t trade time for money or money for time.

Leaving a Penny

I think the only way out of this is to help each other—even when it feels like no more than a penny’s worth. Little things matter. I’ve seen it in my own life.

There are a few families on our soccer team that carpool to practice. Freeing up one night per family, per week makes a difference. When other families at our school keep an eye out for our kids and we keep an eye out for theirs, it makes a difference. When someone comes with their pickup truck to help move some furniture, it makes a difference.

All these little things are like those old cups at grocery stores that said, “Have a penny, leave a penny. Need a penny, take a penny.” Little things that show up where you’re squeezed matter a great deal.

And something that feels small to us—like just giving a penny—can feel like receiving a gold coin to someone else.

For example, me shoveling my older neighbors’ snow barely registers as 20 minutes of extra work for me, but it’s unbelievably helpful to them so they aren’t beholden to unreliable help when they need their driveway clear to go to a doctor’s appointment.

Similarly, it felt very small to her when a good friend and neighbor came over to watch our kids for 20 minutes when Griffin was born and Robyn was conveyed by ambulance from the living room to the hospital—but to us, it was worth more than a bag of gold.

When we leave and take pennies, it relieves the squeeze. These little pennies are hardly worth just one cent—they’re often worth their weight in gold. “One cent” can feel like salvation when you’re being crushed.

I feel squeezed every single day of my life.

If I could afford to throw more money at problems, I would. But most of my problems wouldn’t get that much better with more money—grocery delivery doesn’t save me a trip because it’s never right, and I’d never be willing to outsource going to my sons’ soccer games, even if we could afford it.

And I’m unwilling to detach either. I’d rather live with the guilt of not meeting my commitments to my friends and people in need, rather than pretending like it doesn’t matter. Because it does. I don’t want to be less squeezed just for me, I want to also be there to stick up for those who have no penny to give.

I don’t think changing laws can help us, in the immediate anyway. I don’t think AI will save us either. The financial windfall that will allow me to gain hours of my time back is never going to come. And I’m tired of waiting for a hero to save me. We are the only heroes we’ll ever get.

The only way this works is if we help each other.

It’s good enough for it to be in small ways. These small acts of support are the only real alchemy I’ve ever seen work. Because when we leave a penny, it’s not one cent we’re leaving—we’re leaving something for someone else that’s worth its weight in gold.

So if you’re feeling squeezed, we need to stick together. Remember this mantra: take a penny, leave a penny. We are all we’ve got, and we are enough to get through this.

Witnessing our kids’ suffering

The path between ignoring suffering and taking control of it.

Witnessing the suffering of others—and how we react when it happens—is a skill.

Unfortunately, it’s a skill that’s underrated—and perhaps not even named—for how important it is, especially for us as parents.

I’ll give this skill we need a name: witnessing.

Let’s imagine a simple example: our child is upset because their favorite flavor of potato chips is out of stock at the grocery store.

An obviously damaging response would be:

“Screw you, stop complaining. You have no idea how small this is or how good you have it. Shut up, go sit alone in the corner, and feel stupid until you figure it out.”

A seemingly more considerate—but equally damaging—response would be:

“Oh my goodness, I’m so sorry. Let me do whatever I can to help you deal with this. Should I drive 15 minutes right now to find that flavor for you?”

The first response makes them feel valueless.

The second infantilizes them, giving them evidence to believe they’re incapable of enduring anything hard.

The problem is, both of these approaches absolve us—as parents—of the horrific feeling we get when our kids suffer.

The first allows us to disconnect from the feeling.

The second allows us to solve the problem and make it go away.

Both prevent growth. Both delay the issue of suffering and compound it.

Because instead of helping them deal with suffering now, we displace it—until we’re gone.

The urge we have, as parents, is to end suffering as quickly as possible.

But we can’t. We have to let it run its course.

Of course, like with any other human being, if someone is in mortal danger, we must intervene.

But as parents, we do this too quickly. Or at least I do.

I end the suffering—not because my kids can’t deal with it, but because I can’t.

So what do we do instead?

If we don’t tell them to suck it up, and we don’t cater to their every need, what do we do?

I think the answer is hard, but not complicated.

Just show up and listen. That’s the balm.

Be next to them. Listen.

Offer comfort, ideas, and—if they’re open to it—stories about our own mistakes. I think all wr need to do is be there and stew in that suffering with them.

Unfortunately, this prolongs our discomfort and stifles our sense of control as parents.

But it’s the better, third way: to let them live their lives—a little more with each passing day.

Letting go, without disappearing.

That’s the delicate ballet we dance as parents: to witness their suffering without taking it on as our own.

When we witness—not control, and not ignore—our kids’ suffering, we find a delicate place we can occupy.

That’s both the place where our kids learn. And where we grow our character and mettle as parents.

The cost is our sadness, and sometimes our sanity.

But if witnessing—not ignoring and not controlling—allows our kids to grow in courage, and forces us to strengthen and purify our own souls, that is a price worth paying.

We are hybrid dads, and we GOT THIS

Men today are living through a reset in gender roles. Fair Play by Eve Rodsky is a great book to help navigate this change.

In this post, I’ve also include a Fair Play PDF template you can use on Remarkable or another writing tablet.

If you’re a dad like me, juggling work, home life, and your role as a partner, let me tell you—you’re not alone. We’re the first generation of dads stepping into this new space, trying to figure out what it means to be fully present as fathers and equal partners in our relationships. It’s not easy, but it’s ours to own.

We’re hybrid dads. We’re building something new, something better—and it’s time we talked about how to get there together.

A hybrid dad isn’t defined by tradition or rebellion—it’s about creating a role that works for your family. It’s part breadwinner, part partner, part parent—and 100% intentional.

Why Men Should Read Fair Play

If you’re a millennial husband or father, I think you should read Fair Play by Eve Rodsky. Or, if you know a millennial husband or father—especially one who’s quietly trying to balance home life, work life, and being a good, equitable partner—gift them this book. Even if it doesn’t seem like it’s “for them,” it just might be what they need.

It was a game changer for me personally, and also for our marriage.

The book offers both a mental model for what a fair balance of domestic responsibility can look like in a partnership and a practical system to manage those responsibilities with clarity and efficiency. It’s dramatically reduced the friction Robyn and I used to experience while running our household and managing our family system.

For example, cooking and meal planning used to be a source of endless improvisation and frustration. We’d either figure everything out together or constantly reset our schedules on the fly. It wasn’t working. Now, we’ve set roles: I’m the weekend chef, and Robyn’s the weekday chef. I used to handle groceries, but it made more sense for her to take over, and we adjusted intentionally. Knowing exactly what ingredients she needs and when has made the process seamless, thanks to concepts we learned in Fair Play like the “minimum standard of care.” These ideas helped us have conversations about fairness and efficiency without resentment.

This shift gave us more than just better logistics—it gave us peace.

And that’s what we need in this reset—peace of mind, clarity, and confidence. Because this isn’t just about household chores; it’s about redefining what it means to show up as dads and partners in a way that works for us.

A Reset for Men

There’s been a lot of talk about how men are struggling. The data is there, and the anecdotes are everywhere. To me, all of this is true—but I see it more as a practical and personal phenomenon than an abstract crisis.

As a man, I think of it as a reset.

Here’s why I hate the “crisis” framing: It feels emasculating. When people talk about us as a lost generation of men, it’s hard to engage with that narrative—it feels like a judgment, like we’re failing somehow just by existing in this moment of change.

That’s not helpful, and frankly, it’s a turn-off. It makes me want to disengage.

I don’t see us as victims, and I’m not interested in crisis rhetoric. What I see is an opportunity to reset and redefine what it means to be a husband and father.

A generation ago, gender roles were simpler—though not necessarily better. The man worked outside the home, often as the breadwinner, and there were plenty of examples (good and bad) of what that looked like. Today, it’s different. Many men aren’t the sole earners anymore, and many of us are leaning into home life and parenting in ways our fathers didn’t.

The problem? Most of us don’t have a blueprint.

Few of us had dads who split domestic responsibilities equitably. Fewer still had dads who volunteered at the PTA or took paternity leave. We’re making this up as we go because we’re the first generation actively navigating pluralistic gender roles.

And that’s the beauty of it: There’s no one way to be a good husband or father anymore. Traditional roles can work, but so can new hybrids. What matters is that we’re intentional about creating a family system that works for us.

We are hybrid dads—we’ve got each other’s backs, and we GOT THIS.

How Fair Play Helps

Fair Play gave Robyn and me a language to talk about our family system and decide how we wanted it to work. By breaking responsibilities into categories—from chores to self-care to parenting—we could set standards for our household and adjust as life changed.

For us, this meant defining who “owned” which tasks. For example, when my work schedule changed, we switched roles for groceries.

In addition to the book, we also bought Rodsky’s flashcards and found it helpful to “redeal” physical cards every few months.

I also created a PDF template to keep track of all this and reset my focus weekly on my Remarkable.

You can download my PDF template here.

The results? Less tension at home. Less self-doubt about whether I’m doing the right thing as a husband or father. And something even more meaningful: more joy.

By being more involved at home, I’ve gained something many men in previous generations didn’t have—deep, priceless time with my kids and my wife. The joy that comes from being fully present, from knowing I’m not just managing but thriving as a dad and partner, is worth every effort.

Why Men Should Read This Book

If you’re a man in this “reset” generation, Fair Play is a godsend. It’s not just about managing tasks; it’s about finding confidence in the type of husband and father you want to be.

We may not have role models for this new way of being a man, but we don’t need to feel lost. Fair Play gives us a framework to build our own hybrid roles—ones that work for our families, bring us closer to our partners, and let us embrace the joy of being present.

I recommend this book to any man navigating this shift. Read it. Try the system and the cards. Download the template. See how it changes your home life.

It sure as hell changed mine.

Parenting is an act of faith

My costliest mistake as a parent was trying to make my sons’ world more like mine.

Friends,

It’s a joyous time for us. Not only are we getting ready to welcome our fourth child, but many close friends and family are either having children themselves or moving out of the newborn phase of life.

When you’re expecting, love starts pouring in from all directions. The fraternity of caregivers—parents, grandparents, aunts, uncles, “aunts,” and “uncles”—is built on love. And when others join that fellowship, all you want to do is pay that love forward.

I feel that deeply right now.

As we all know, there’s no foolproof playbook or universal script for parenting—no single piece of sage wisdom we can all rely on. But what we can do is share our biggest mistakes in the hope that others might avoid them. After all, mistakes tend to be more universal than we’d like to admit.

Mine was this: I was a colonizer.

When my kids invited me into their world, I tried to reshape it—imposing adult order with schedules, tasks, and structure. I thought I was helping. But that approach cost me years of connection during our older kids’ youngest years.

This week’s episode of the Muscle Memory Podcast is about that very mistake—and what I’ve learned since. I hope you enjoy it.

With love from Detroit,

Neil

Days Like These: A Father’s Wish

I wish for another day where we celebrate at a table more crowded than the year before.

I forget sometimes how large I loom in their world. But on this Father’s Day, I am reminded of it, and it’s something I don’t want to forget.

All my sons put so much effort and care into my Father’s Day present. It helped me remember that, no matter who you are, as a young kid, the people who raise you are your whole world. Mothers and fathers are just…giants to a kid. All children explore this, fascinated and in awe. That’s why all kids put on their parents’ shoes and mittens and walk around in them.

“Maybe someday,” we wish, “these will fit and I’ll get the chance to be like them.”

Mothers and fathers are giants to a kid.

This is such a gift of love, not just for our joy and hearts but for the people we will become in the future.

I’ve been thinking about how this year, on my birthday, my perception of age changed. When we’re young, the first change comes when you realize how awesome it will be to be older: bigger, stronger, and more free. Then you hit the invincibility years of your twenties, wishing to stay 27 or 28 forever.

Next come the years of control—or lack thereof, I suppose. There’s not enough money, not a good enough job, the kids grow up too quickly, and you find yourself nervously joking about the increasing gray in your hair or talking about revisiting old haunts to recapture fleeting youth.

Then my 37th birthday hit, and my perception of age changed again. It was a birthday where I thought, “Damn, I’m just glad to be here for it.”

Why? Because I became very conscious of how our table grew more crowded this year, not less. This year, we’ve added children, brothers, and sisters to our table of friends and family. And we lost almost nobody. I’m old enough now to realize how rare and precious birthdays like this one will be from here on out.

So yes, when I blew out the candles on my pineapple birthday cake this year, my wish was: “Thank you, God, for letting me celebrate this birthday. My wish is for my next birthday to be like this one, with our table more crowded, not less.”

One of my greatest fears about death now is not the pain, suffering, and uncertainty that surrounds it—though that’s still a real fear. I have started to fear that a birthday will come—especially if my friends and family are gone, and I’m the last one standing—where I won’t wish for another one.

That’s the final change in our perception of age: moving from a place of peace and gratitude for our life—where we’re just happy to be here—to hoping for death to come peacefully, but also soon. I don’t want to ever slip into that last phase of age. I hope this last birthday, where I was just happy to be here and hoped for another birthday, is the last time my perception of age meaningfully changes.

No matter what happens, I know today that I have mattered to my sons. Days like these, marked by little celebrations and small gestures of love, remind us that we mattered to someone—whether it was our kids, friends, family, colleagues, or neighbors—that we loomed large.

These little Father’s Day gifts, like the ones I received today, are more than just presents. They are symbols we can hold onto as we age, reminders that we loved and were loved. These symbols of love will always give me hope and a feeling of worth, a reason to keep wishing for more birthdays. Because we were loved once, there’s always hope that each day we wake up, there will be that light of love again—whether it comes to us or is the light we carry and gift to others.

The Steady Years: Strengthening Marriage in Comfortable Times

How do we strengthen our marriage, when our week-to-week is steady and consistent?

There are no existential threats to our marriage, and maybe that’s why I feel like this phase is so dangerous.

We are no longer newlyweds. We are no longer new homeowners. We are no longer new parents (or dog-parents). We aren’t going to be sending our kids to a new school for at least 8 years. We aren’t new anythings, and if everything goes to plan, we won’t be new anythings for a while.

Our life is in a spot where it’s pretty settled in as “parents of young children”. We won’t have kids that are either into high school or have all of them into kindergarten for 4 to 6 years. Neither of us are in a place where we’re likely to have rapid career growth - partly by choice.

Our marriage is feeling really settled in, with very little that may rock the boat unless something tragic happens in our extended family, God forbid. The water ahead isn’t placid, but we’re aren’t in stormy waters either. It feels like we’re just in a place of “keep the chains moving” or “one foot in front of the other” or “turn the crank.”

In a way, our lives are so stable. After the past decade with tons of change, it feels so bizarre to think that a season of sustainability and relative peace could be dangerous to our marriage. But I think it is. This seems like a time where it could be so easy to just do what we’ve always done. For things to get boring. For things to get not just comfortable, but so comfortable that we float and drift, without even realizing that our marriage isn’t anchored.

I worry that it would be so easy to mindlessly go through the motions for the next 4-6 years. That we get to 2030 and our marriage is stiff or slightly zombie-like, because we’ve gone half a decade getting so in the groove that we no longer have to give 100% attention to our marriage and family life.

I don’t think the way out of this is to seek crises. All the crises we’ve had have certainly made our marriage stronger, starting with my father’s passingly nearly 8 years ago. Even though that season, and other difficult seasons, have made us stronger - it came at high price: sadness, suffering, anxiety, and wounds. Looking for crises is an option, but that can’t be the best way to keep deepening and strengthening our marriage.

At the same time, I don’t think the full solution is to amp up novelty either. We could go on lots of fancy trips. We could eat out and go to the theater a lot more. We could move to a new house, just to liven things up. We could do any number of things to spice daily life up. But would that really lead to strength?

Sure, novelty is fun, and if we’re laughing and having fun it’ll make things feel good and positive. We’ll be able to keep things from getting stale. We definitely need some level of new and fresh - we’re only human.

But our time and money have constraints - it’s not unlimited. We can’t buy novelty indefinitely.

And moreover, how much can novelty strengthen our marriage? Surely, there are diminishing returns after a certain point. After a certain point, have we really deepened our connection or brought something more of ourselves to the marriage? At what point does novelty become a crutch or a stopgap?

I think there is a third way to strengthen marriages in these stable-but-could-be-dangerous years without entirely depending on crises or novelty: little sparks.

I figure, maybe I could try to just dial in extra deep for little moments of our days and weeks. You know, just throw in a little extra. Maybe when I’m making a pizza, I try some black pepper on the crust in addition to garlic salt. Maybe, it’s a little “I love you” post-it note I could hide in Robyn’s sock drawer every once in awhile. Maybe I try just a little bit harder to be extra specific when Robyn asks me, “how was your day, Honey?” It could even be just remembering to make real, genuine, loving eye contact at least once after the kids go to bed and we’re talking.

I really mean little sparks as just that: little. Nothing grand or flashy. Just little, intentional, things that lock me back to a state of attentiveness. Little sparks that say to Robyn, “I know our lives feel pretty similar every week, but I’m not daydreaming through it, I’m here with you in it.”

These little sparks are probably even me just proving to myself that I’m not mailing it in and that I’m digging deeper. That I’m paying attention. That 100% of me is still here.

These years, God willing, will be stable and not riddled with crises, grief, or existential threats to our marriage. But there’s no free lunch. If we have stability, it means we have to fight against the calcification that these stable-but-could-be-dangerous years could catalyze.

These years, where our kids are little, will certainly be some of the sweetest that we will have, and they already are. But we can’t let our marriage atrophy through it. That’s not a price I’m willing to pay. I want to make these little sparks so that once these years are over, we’re not going through the motions of our marriage for the rest of our days, relegated to reminiscing about the good ol’ days where our kids were little.

No, I want to be stronger and deeper in love and marriage than we were when we started this season of our life. This time doesn’t have to be dangerous, it can be a time of renewal if that’s what we make it. We can renew our marriage if we ride out the crises, add a dose of novelty, and stay committed to making those little sparks in our daily life.

2023: The Year of ‘Not Helpless’

2023 taught me a powerful lesson: facing fears and owning up to my choices proves that, really, we're never helpless.

My biggest regret this year was not attending a memorial service for someone I knew who died unexpectedly.

Despite our distant connection, my grief was real, but fear held me back. I worried about navigating the unfamiliar customs of their faith and feared saying the wrong thing to their family, whom I had never met before. Additionally, I was concerned about how others would perceive my attendance, given our weak ties.

Upon reflection, none of these fears justify my absence, and this regret has been a poignant lesson for me. It seems so obvious now, but I actually have some control over how I react to fear. Nothing but myself was stopping me from making a different choice.

I am glad that even though I feel regret, I have learned something from it: My ignorance is my responsibility and under my control. My irrational fears are my responsibility and under my control. My boundaries and response to social anxiety is my responsibility and under my control. These are all hard, to be sure, but I am not helpless.

—

I’ve now proven to myself that I can do better. This is my greatest accomplishment of the year.

On vacation, where work stress dissolves into the Gulf of Mexico's salt, I find myself more patient with my sons. In the last two months, gratitude journaling helped me realize that I was unfairly expecting my sons to manage my frustrations. This insight has made me a better listener, helping me see them as they need to be seen - closer to how God sees them.

On vacation, when the stress of work dissolves into the Gulf of Mexico’s salt, I am more patient with my sons. In the last 2 months of the year, when some gratitude journaling I did finally made it click that I’m expecting my sons to help me manage my own frustrations, I am better. I am a better listener and I finally see them in the way they need me to - closer to how God sees them.

Now, I know, I can do better - I just have to do it when the world around me feels chaotic and when we’re out of our little paradise and back into our beautiful, but very real, life. This will be extremely difficult, but I know I can do it, because I’ve already done it.

Once I am better - as a listener, as a father, and as a husband when Robyn and I work through this together - I start to talk to them different. I’m curious. I’m asking questions. I’m taking pauses. I’m no longer trying to control and react, I am the powerful wave of the rising tide that is firm but gentle, enveloping them and their sandy toes until they are anchored again.

I change how I talk. Instead of saying - “stop it, now!” I start to say, with a full, palpable, sense of love and confidence in them - “you are not helpless.”

—

Over the years, Robyn and I have taken exactly one walk on the beach together during our Christmas vacation.

We saunter away for 30 minutes at nap time, letting the masks we so reluctantly maintain as parents and professionals fully drop. It's just us, speaking to no one except three young girls who earnestly and eagerly approach us, asking, “Excuse us, but would you like a beautiful sea shell?“

Some years, one of us is weeping as our grief and frustration finally is allowed to boil over. This year though, we are incisive and contemplative. I am honestly curious. We struggled so much this year, how is it that we aren’t more frustrated with each other?

By the end of our walk and our conversation, I see her differently. She is more beautiful, but that’s how I feel everyday. Today, I also feel the depth of her soul and resolve more strongly. Her gravity pulls me in closer.

We have fought hard to get here. All the hard conversations we’ve had and all the conflict resolution techniques we’ve studied and applied have made a big difference. Yes, we have put in the work.

But at the root of it, is something much deeper and strategic. We have seeds of resilience that we have planted consistently with every season of our marriage that passes. We plant and reap, over and over, not a fruit but a mindset. We have vowed to be in union. We are dialed into a single vision that is bigger than both of us. We are committed to make it it there and we have jettisoned our escape pods, figuratively speaking, we have left ourselves no choice but to figure it out.

And with every crisis, we feel more and more that we can figure it out. With each year that passes, the difficulty of our problems increases, but so does our capacity to manage them. More than ever, as the clock strikes the bottom of the hour and we end our saunter, I remember - we are not helpless.

This year was hard. But the silver lining was that I finally internalized something so simple, but so important.

When the going gets tough - whether it’s because of death, our children growing up, or external factors adding stress to our marriage - nobody is coming to save us. We are on our own. But that’s okay, because we are not helpless.

We Are Everyday Artists: Seizing the Canvas of Daily Routine

The world needs more people to function as artists in everyday life.

What is an artist?

Three things define an artist: a point of view, refined craft, and canvas. This is my interpretation, and I'll elaborate shortly. Here’s a thread on ChatGPT for a summary of different schools of thought on what an artist is.

We can be artists in our day to day lives. Parenting can be artists’ work. Leadership can be artists’ work. Yes, artists create plays, music, paintings, and dance - but fine and performing artists are not the only artists there are.

We are all capable of being artists within our respective domains of focus. We should.

Artist = point of view + refined craft + canvas

Artists have a point of view. A point of view is a unique belief about the world and the fundamental truths about it. Put another way, an artist has something to say. A point of view is not necessarily something entertaining or popular, but I mean it as a deeper truth about life, the world, ideas, or existence itself.

A point of view might be and probably should be influenced by the work of others, but it’s not a point of view if it’s copied. To be art, the artist must internalize their point of view.

Artists have a refined craft. Artists must be able to bring their point of view to life and communicate it in a novel, interesting, and compelling way. Bringing their point of view to life in this way takes skills and practice. And it’s not just technical skills like a painters brush technique or a writer’s ability to develop characters, part of the skill of being an artist is the act of noticing previously unnoticed things, or, the ability to connect deeply with emotions, feelings, and abstract concepts.

A refined craft might be and probably should be influenced by the work of others and exceptional teachers, but it’s not a refined craft if it’s mere mimicry of someone else. A refined craft is something that the artist has mastery in.

Artists have a canvas. The point of view that an artist brings through their refined craft must be manifested somewhere. Painters literally use canvasses. For dramatic actors, their canvas is a stage performance. For muralists, their canvas is the walls of large buildings.

However, those mediums do not have to be the only canvas. For a corporate manager, their canvas might be a team meeting. For someone cooking a family dinner, their canvas might be the dinner table - both the food and the surrounding relationships. For a parent, their canvas might be their nightly bedtime routine. For someone just trying to be a good person, their canvas might be their bathroom mirror or journal, where they reflect on how their actions have impacted others.

And for what it’s worth, a canvas doesn’t have to be the center of a performative act. A canvas is merely the medium. Who sees the medium, and its level of public transparency, is an entirely different question.

Examples really bring what I mean to life. I’ve asked ChatGPT to apply the Artist = point of view + refined craft + canvas framework to a handful of people. This link will take you to an analysis of Frida Kahlo, Jay-Z, Steve Jobs, JK Rowling, Oprah Winfrey and others.

We need artists

What I find so compelling about artists is they move society and culture forward. In some ways, people who operate as artists are among the only people who can progress us forward. Why? First, artists operate in the realm of beliefs, which means they can change the deepest parts of people’s minds. Second, because artists bring a novel perspective to the table, they’re people who cut against the grain and challenge long-held norms, by definition. Artists make a difference by making things different..

This is exactly why I think we ought to operate as artists, especially in our daily lives as parents, colleagues, and community members. I believe things ought to be different and better. Kids, on average, deserve better parents. People working in teams, on average, deserve better colleagues and leaders. Communities, on average, deserve a better quality of life.

We are fortunate to be alive now, but there is room for improvement. Daily life for children, workers, and citizens ought to be much better because there is still so much unecessary drudgery and suffering.

Moreover, there is insufficient abundance for everyone to pursue a career as a fine artist or performing artist. Conventional art is invaluable, but not feasible for most to pursue professionally or as a hobby. For most of us, the only choice for us is to act as artists at home, work, or in our communities.

Again, I think examples bring it to life. Here are three personal examples that illustrate that we can think of ourselves not just as parents, leaders, or citizens, but as artists. (Note: my examples don’t imply that I’m actually good at any of these things. It’s an illustration of how one might think of these disciplines as art).

As an artist-parent…

I believe…that I am equal in worth to my children and my job is to love them and help them become good people that can take care of themselves and others. I’m merely a steward of this part of their life, and that doesn’t give me the right to be a tyrant.

Part of my craft is…to reflect questions back at them so they can think for themselves. So if they ask, “Should I ride my bike or scooter on our family walk?” I might reply, “What should you ride, buddy?”

My canvas…is every little moment and every conversation I have with my kids.

As an artist-leader at work…

I believe…our greatest contributions come collaboratively, when we act as peers and bring our unique talents together in the service of others.

Part of my craft is…creating moments where everyone on the team (including our customer) has time to speak and be heard - whether in groups or 1-1 behind the scenes..

My canvas is…team meetings, 1-1 meetings, and hallway conversations where I am in dialogue with colleagues or customers.

As an artist-citizen…

I believe…we will reach our ideal community when there is leadership present on every single block and community group.

Part of my craft is…find new people in the group and ask them to lead something, and commit to supporting them.

My canvas is…neighborhood association meetings, conversations while walking my dog, and the moments I’m just showing up.

We can be artists. Even if we can’t paint, even if we can’t dance, even if we can’t write poetry - we can be artists.

How we become everyday artists

The hard question is always “how”. How do I become an artist-parent or artist-leader? This is an important and valid question. Because these ideas of “point of view” and “craft” are so abstract and lofty.

What has made these concepts practical to attain is starting with my mindset. We can act as if our environment is a canvas.

So no, the team meeting at work isn’t just a meeting - it’s a canvas. And no, the car ride to school isn’t just 15 minutes with my sons to kindergarten or daycare drop off, it’s a canvas. These are not ordinary moments, I need to tell myself that I’m an artist and this is my canvas.

Because when I treat the world like a canvas, it goads me into considering what my point of view is. Because what’s the use of a canvas without a point of view? The existence of a canvas persuades me to form a point of view.

And when I think about my point of view, it nudges me to consider and hone my craft. Because what’s a point of view without the ability to bring it to life? Once I have a point of view, I naturally want to bring it to life.

Treating the world around me like a canvas is both under my control and the simple act which snowballs me into practicing as an artist in everyday life.

If you think being an everyday artist has merit, my advice would be to pursue it. Just start by taking something ordinary and make it a canvas. Because once we have a canvas and take our canvas seriously, an artist is simply what we become.

Photo by Anna Kolosyuk on Unsplash

The Art of Adjusting: Our Journey from Zero to Three Kids

We survived by learning to make adjustments.

From the outside looking in, the transformation from a couple to parents, and then to a family of five, might seem just like a change in numbers. But the journey of adjusting to each addition, the evolving dynamics, and the never-ending learning curve is a tale unto itself. Every family has its unique narrative, and ours is filled with moments of joy, chaos, discovery, and reflection.

People often ask about our journey – perhaps out of curiosity, or maybe because they're embarking on a similar path. By sharing our story, I hope to offer some insights and perhaps provide a sense of camaraderie. Parenting, after all, is a shared experience. No matter how many children you have or plan to have, it’s beautiful and impossibly hard. I've taken this opportunity to reflect on our changes, the big and small adjustments, and the lessons we've learned along the way.

Whether you're here seeking understanding, relatability, or just a story, I invite you to join us on our journey from zero to three kids. I love talking about this because I usually learn something by being asked to reflect on it.

In each phase, we've had to fundamentally rethink our roles—as parents, partners, friends, and colleagues. Every phase has required different adjustments. I’ve shared some of our experiences here. Have yours been similar? Different?

Comparing notes with other parents is really helpful to me, so if you’re so inclined - I’d love to hear what you think in the post comments or in the comments on Facebook.

Moving from Zero to One: Schedules Became Crucial

The biggest adjustment moving from no children to one child was schedules. Oh lord, was that hard. The entire rhythm of our day changed, becoming centered around the rhythms of our son.

This was so much more than “not sleeping.” How and when we socialized radically changed. How and when we had to get home from work also saw significant shifts. The pace with which we moved through the day became much slower because we were on “baby time.”

The personal adjustments I had to make were largely centered around work. I had to set boundaries around my work schedule because of drop-off duties. If I ran late, I would miss reading Robert a story and putting him to bed. I also realized that my needs were no longer the center of the universe.

In addition to our schedule's rhythm changing, it was a significant mental and emotional adjustment (read: ego check) to let go of the flexibility and decision-authority over my time. As someone who has been independent my whole life, I grieved the loss of freedom over my time and personal autonomy—even down to when I could use the bathroom.

One thing I'm glad we didn't compromise on was our passion for travel and adventure. Travel, especially to see or spend time with family, is non-negotiable for us. That was one aspect we didn’t adjust; we continued our daytime adventures. We even took a 10-month-old to Japan, which, looking back, seems audacious, but that was non-negotiable. It was something our son had to adapt to.

Moving from One to Two: No Slack in the System

When Robyn and I had one child, we could muscle through without having to change everything drastically. But with the arrival of our second child, there was no slack left in our system. There was no longer a quiet time; someone in our household was always awake or had a need. With a second child, the opportunities for quick naps or swiftly loading the dishwasher vanished, straining our family system. It's no surprise; systems without slack tend to be fragile.

Robyn and I found ourselves adjusting and transforming many of our individual and shared habits. We had to create and refine systems. Logistical systems came into play, including semi-automated grocery lists, whiteboard calendars, and chore wheels. We delved into Eve Rodsky’s system from her book Fair Play: A Game-Changing Solution for When You Have Too Much to Do (and More Life to Live) even adopting her flashcards. These tools and others made us more efficient and disciplined, ensuring we still had moments to recharge individually and as a couple.

Above all, we focused on managing conflicts. We prioritized our weekly temperature checks, revisited our five-year vision regularly, and committed to addressing issues head-on, turning towards each other, especially during misunderstandings. The crux of our adjustment was nurturing the courage to speak honestly and remain emotionally present, particularly when faced with hurt.

Moving from Two to Three: Navigating Dreams and Inner Demons Amidst Chaos

Parents often quip that introducing a third child means shifting defense from "man-to-man" to "zone." Suddenly, with three kids, Robyn and I were outnumbered. Our life was a whirlwind of chaos.

This phase was more about acceptance than change. Our vision of life underwent a transformation. Dreaming of a perpetually clean house? Unrealistic. Juggling a demanding job and being a hands-on parent? A choice had to be made. Aspirations for rapid career growth had to be balanced against family time. And the home projects I'd hoped to save on by DIY-ing? Either hire a professional or set them aside.

These dreams and life yardsticks had to align with our reality. Despite being well-off and having considerable family support, realizing we couldn't "have it all" was a pivotal moment. Accepting our third child meant reimagining our dreams. Our family had tangibly, unquestionably, and irreversibly became the cornerstone of our aspirations and future vision. This shift was profound, given the pressure I had placed on career goals, community involvement, and personal achievements.

However, this chaotic phase prompted major parenting adaptations. At least one of our children always seemed to be navigating a major transition or facing emotional challenges. With three kids, there's always a storm brewing. Such turbulence often brought out the worst in me, rather than my best. I fell back into negative behavior patterns and made numerous parenting missteps. Moments arose when I'd ponder, "Am I this guy? Am I going to accept being this guy?"

This chaos demanded introspection. My internal world underwent a shift, prompting me to confront deep-seated fears, angers, and skill gaps. We sought therapy, and became a Dr. Becky Good Inside family. And slowly, we began walking the long road to change.

How We Adjust

Naturally, my reflections often circle back to the theme of adjustments. Adjustments are vital, but the process is far from trivial. So, how do we make these shifts?

Firstly, a vision is paramount. How do you envision the future? Taking time to dream, both alone and with loved ones, is essential. We need direction, and clear picture of the ideal future; without it, there's no reference point for when change is needed. The moments Robyn and I have spent articulating our dreams have been some of the most rewarding in our marriage.

Secondly, for effective adjustment, clear priorities are paramount. We all harbor grand dreams and visions, but reality doesn’t always align. The world is filled with trade-offs, constraints, and unforeseen events. Time and resources are finite, so we can’t achieve everything we desire. To navigate these challenges, we must prioritize the dimensions of our dreams. It’s these priorities that serve as a compass, guiding which adjustments to make.

For instance, faced with the demands of parenting and career, which takes precedence? Robyn and I chose to adjust our career paths to be more present for our children. While this wasn’t our initial plan, our priority of being active parents necessitated this change. Such decisions, pivotal in shaping our lives, are rooted in understanding our core priorities.

Lastly, genuine listening complements our prioritization. To assess whether we need to make adjustments we need accurate feedback. Are we veering in the wrong direction? We need information to know whether an adjustment is urgent. That information might be explicit like a bank statement or cholesterol panel, or it could be through observation of our kids’ feelings and behavior, or even information gleaned from personal reflection and discernment.

Adjusting is an art form and is ongoing, evolving with each phase of life. I'd love to hear your thoughts, whether you're a new parent or have had a decade's worth of experience. I'm sure each of you has your unique tales, moments of revelation, and personal strategies that you've leaned on. Whether you're just starting your family or have been on this journey for a while, I'd love to hear from you.

Discussion Points:

Journey Reflection: If you have children, what were the most significant adjustments you made with each addition?

Learning Moments: Were there any unexpected lessons you learned along the way?

Balancing Acts: How have you balanced your personal dreams and aspirations with the needs of your growing family?

Feel free to share in the comments below or reach out on Facebook. Let's continue the conversation and learn from each other's experiences.

Key Takeaways:

Moving from Zero to One: Adjusting to the rhythm of your child is paramount. Personal sacrifices, especially around time and autonomy, are inevitable.

Moving from One to Two: Systems and routines become critical. External tools and relationship checks (like Fair Play) can be invaluable.

Moving from Two to Three: Embracing chaos and re-evaluating personal dreams and professional aspirations are essential. Prioritizing family becomes a central theme.

Photo by Julian Hochgesang on Unsplash

The Dynamic Leader: Parenting Lessons for Growing a Team

How often we adjust our style is a good leadership metric.

In both life and work, change isn't just inevitable; it is a vital metric for assessing growth. My experiences as a parent have led me to a deeper understanding of this concept, offering insights that are readily applicable in a leadership role.

Children Grow Unapologetically

As a parent, it’s now obvious to me that children are constantly evolving, forging paths into the unknown with a defiance that seems to fuel their growth. Despite a parent’s natural instinct to shield them, children have a way of pushing boundaries, a clear indicator that change is underway. This undying curiosity and defiance not only foster growth but necessitate a constant evolution in parenting styles.

Today, my youngest is venturing into the world as a wobbly walker, necessitating a shift in my approach to offer more freedom and encouragement, but with a ready stance to help our toddler the most dangerous falls. Meanwhile, my older sons are becoming more socially independent, which requires me to step back and allow them to resolve their disputes over toys themselves. It's evident; as they grow, my parenting style needs to adapt, setting a cycle of growth and adaptation in motion.

The Echo in Leadership

In reflecting on this, I couldn't help but notice the clear parallel to leadership in a corporate setting. A leader's adaptability to the changing dynamics of the team and the operating environment is critical in fostering a team's growth. If a leadership style remains static, it likely signals a team stuck on a plateau, not achieving its potential.

A stagnant leadership style not only hampers growth but fails the team. It is thus imperative for us as leaders to continually reassess and tweak their approach to leadership, ensuring alignment with the team's developmental stage and the broader organizational context.

This brings me to a critical question: how often should a leader change their style? While a high frequency of change can create instability, a leadership style untouched for years is a recipe for failure. A quarterly review strikes a reasonable balance, encouraging regular adjustments to foster growth without plunging the team into a state of constant flux.

Conclusion: The Dynamic Dimension of Leadership

In the evolving landscapes of parenting and leadership alike, adaptability emerges not just as a virtue but as a vital gauge of growth and effectiveness. Thanks to my kids, I was able to internalize this pivotal point of view: understanding the dynamic or static nature of one's approach is central to assessing leadership prowess.

For leaders eager to foster growth, the practice of self-assessment can be straightforward and significantly revealing. It is as simple as taking a moment during your team's quarterly goal reviews to ask, "How has the team grown this quarter?" and "How should my leadership style evolve to support our growth in the upcoming period?"

By making this practice a routine, we can ensure that our leadership styles remain dynamic, evolving hand in hand with our teams' developmental trajectories, promoting sustained growth and productivity.

Photo by Julián Amé on Unsplash

I promise to not be a superhero

Constantly being angry is what I find hardest about being a father.

As a father, I am angry about something almost every day.

To be clear, I don’t like being angry. For me, constantly being angry is the hardest part of being a parent, even harder than changing diapers or staying up all night with a sick child.

Sometimes I feel angry because of something one of my sons did, say, punching me in the stomach while having a tantrum. In that case, I am angry at them and their behavior.

What I’ve realized, though, is that I am not usually angry at them as much as I think. The aftermath of a series of sibling “incidents” this weekend was a good example of this.

I realized I was angry because I’m feeling inadequate as a father right now. One of our sons is going through something painful - he wouldn’t deliberately abuse his younger brother if he wasn’t in some deep emotional spiral - and I haven’t been able to help him. He’s a good kid who needs the care of a father, and I’m failing.

It makes me angry that he throws Hot Wheel cars at his brother without provocation, sure. But I’m not angry at him, as much as being angry at myself.

I’m angry that he’s going through genuine suffering about something. I’m angry that I don’t know what it is. I’m angry that I can’t help him. I’m angry that Robyn has exhausting days at home intervening to mitigate the effects of volatile behavior, on top of her heavy work schedule.

I’m not angry at him, I’m angry at myself for letting the side down.

This seems obvious, but it has been a revelation. Practically speaking, it’s a much different parenting strategy if I’m angry at him vs. if I’m angry at myself. If I’m angry at my son, that’s a negotiation and a coaching moment. But if I’m angry at myself, I have to focus on getting my own emotional state stable.

After all, how could I help him if I’m not even sturdy? It’s the airplane principle applied to parenting: if I want my son to be calm, so he can realize it’s not kind to spit on my shirt, I have to be calm enough to help him chill out.

This weekend, while reflecting on this, my long-running feelings of guilt, inadequacy, and shame finally surfaced. When my oldest asked me, “will you love me after you die?” Is when I finally lost it.

I love these kids so much, I thought, how can I fail them so badly? How am I struggling so much, even after learning valuable skills in theraphy last year, like “special time” and emotional coaching?

He deserves better.

And yet, I know my self-flagellation is ultimately hypocritical. I’m so particular about telling my sons that, “mistakes are part of the plan, all we need to do is learn from them.” And yet, I have been reluctant to take my own advice, for months now.

I am not a perfect man. I am not a perfect husband or father. My family does suffer, on my watch. The world tells me that this is not what good men and good fathers let happen. Failing at what I care about most - being a husband and father - makes me angry, and honestly, ashamed.

And yet, we cannot allow ourselves to go down this road as fathers or as parents. We cannot be angry at ourselves for not being gods or ashamed that we aren’t superheroes. To do so would be the definition of futile and irrational, because we are not gods nor are we superheros. It is simply not possible.

What we can do is adjust. We can choose to stop being angry at ourselves. And then we can choose to examine ourselves and really listen to the kid in front of us. And honestly, I think an act of adjustment can be as simple: take a pause, do some box breathing, and then ask, “is there something that you’re having a hard time saying?”

Because even though our kids don’t come with a handbook, they, luckily, are the handbook. And then, finally, we can change our posture and try something different.

We can let all that anger, guilt, and shame go so that we can stop making ourselves into crazy people. And then, we can use the energy and clarity we’ve gained to do better.

Let’s say it together, my brothers, today and every day, “I promise not to be a superhero, but a father who listens, who learns, and who loves, even in the midst of my anger.”

Photo by Lance Reis on Unsplash

Deregulating Parenting

There’s a secular lesson to take from Matthew 11: don’t over-regulate children. I want to try, at least, to simplify.

Our parish’s pastor, Father Snow, is about my height. Which means that he’s far shorter than an NBA prospect, though some students at his former parish - Creighton University - were indeed NBA prospects.

Today at mass, our Father Snow gave a homily on Matthew 11: 21-25 which was today’s Gospel reading. To start, he shared an anecdote from his experience at Creighton.

An angry parishioner was lecturing Father Snow about an annulment that she thought the Church shouldn't have given. She was fuming over this application of rules. So much so that one of his giant basketball-playing parishioners stepped in. Putting his elbow on Father Snow’s shoulder, he facetiously asked, “Want me to take her down, Father?”

Father Snow could tell the story better than me, but his point was that too much focus on rules and compliance can be overwhelming. When we fixate on rules they place a heavy burden upon us, chaining us to a slew of anger and stress.

Today’s Gospel reminds us, he said, that Jesus really only had two rules, the first and second greatest commandments: Love God and Love thy neighbor. That’s it. Just two.

In contrast to the 600+ laws imposed upon the Jewish people by the Pharisees, following just two laws is a significantly lighter burden. While this lesson and Gospel reading hold theological and spiritual implications, my immediate takeaway was secular: I impose too many laws on my children.

I have so many rules that underly my parenting. I say “no” all the time, for every little thing it seems, some days at least. If I put myself into the shoes of our sons, I would feel heavy, suffocated even by the grind of the complex, nagging structure of laws I’m imposing.

Surely, a house needs rules about things like not eating ice cream three times a day or not running around naked. But if I’m saying no a hundred times a day, which I think I do sometimes, probably means I’ve gone over the top.

My secular reflection exercise from this biblical lesson - to lighten the burden of rules and laws - was to see if I could simplify my regime of parental law. I wondered, could I get my parenting principles down to two or even just three?

These three are what I came up with. These three principles - be honest, be kind, and learn from your mistakes - can govern every standard I set as a parent.

I’m not trying to advocate for these three rules to become yours if you’re a parent or caregiver, though they fit terrifically for me as a parent. If you like them, steal them.

The more important point I’d advocate is for you to try the exercise. If you’re a parent, caregiver, or even a manager to a team at work, what are the 2-3 principles that you expect others to follow that will govern every standard you set?

It’s not as important what the principles are, as long as they're thoughtful and intentional. What matters the most is that we simplify the burden of our household law to a few principles rather than hundreds.

Even just today, reducing my laws to these three principles has been liberating for me. Instead of trying to regulate every of our sons’ behaviors, I could focus on honesty, kindness, and learning from mistakes.

For example, instead of saying, “stop calling your brother stupid dummy,” I could let this question hang in the air: “It’s important to be kind. Is that language kind?” Instead of having mistakes feel like failure, I could reinforce something they learned. Today it was about how to be kind when sharing food. Tomorrow it can be something else.

I understand that changing my parenting approach will be challenging. After relying on processes and rules for 5 years to establish standards, transforming my behavior will not happen overnight. While every parent is different, I’m confident I’m not the only one who struggles with this.

We can focus on essential principles and free ourselves and our children from a long list of rules by de-regulating parenting. I know I should.

If you try to get your parenting down to a few principles, I’d love to compare notes with you. Please leave a comment or contact me if you give it a go.

—

For those interested, here’s some context for the three principles I’ve been playing with. Again, the point is not to copy the principles exactly, the point is to think about what our, unique, individual ones will be. I wanted to share for two reasons: putting my thoughts into writing helps me, and, I always find it helpful to see an example so I assume others may also find it helpful.

Boys, I have been meditating on it and I don’t want to be a parent that’s obsessed with rules and policing your behavior. One, it won’t work. Two, policing your behavior will not allow you to learn to think for yourself. Three, the level of stress, anger, arguing, and effort required - for me and for you all - having a highly regulated house will be a heavy burden.

I think I’ve come up with three principles that encapsulate the standard of what I expect from myself as a member of this family and community. These are the guiding principles I will use to raise and mentor you. I hope that by centering on three principles that get to the core, we can avoid having dozens upon dozens of rules in our house. Here is what they are.

Be honest.

Honesty is the greatest gift you can give yourself. Because if you are honest, you can have trust and confidence in your own beliefs. And that confidence that your own beliefs and observations about reality are true prevents your soul from questioning itself on what is real. There are no small lies - the uncertainty and pain that lies cause is predictable and omnipresent. One principle between me and you all is to be honest.

Be kind.

Kindness is the greatest gift, perhaps, that you can give to the world. Because if you are kind, you can have trusting relationships with other people. If you are kind, your actions are a ripple effect, making it safer for other people to be kind - and a kind world is a much more pleasant one to live in. Finally, by being kind to others, you can also learn to be kind to yourself. One principle between me and you all is to be kind.

Learn from your mistakes.

Mistakes are part of the plan. They aren’t bad. Quite the opposite - if you’re not making mistakes doing things that are hard enough to learn from or that make an impactful contribution to the world. Mistakes are a feature, not a bug. If we have this posture, it’s essential to learn from your mistakes. Because if you make mistakes and never learn from them, you’ll hurt yourself and others. If you don’t learn from smaller mistakes, you’ll eventually make catastrophic, irreversible mistakes. One principle between me and you all is to learn from your mistakes.

These three principles: be honest, be kind, and learn from your mistakes are our compact. I promise to put in tremendous effort and emotional labor to live by these words that I expect of you. I will hold you to these principles as a standard, but I also promise to help you grow, learn, and develop into them over the course of your life.

Our word is our bond, and these words, my words, are a bond between us.

Thank you teachers, for being the rain

Thank you, teachers, for everything you do and have done - for me, for our three sons, and for all children. We have all yearned for the rain to drench our gardens, and you have made it pour.

The job of a gardener, I’ve realized three years into our family’s adventure planting raised beds, is less about tending to the plants as it is tending to the soil.

Is it wet enough? Are there weeds leeching nutrients? Is it too wet? How should I rotate crops? Is it time for compost? Are insects eating the roots? As a gardener, making these decisions is core to the craft.

The plants will grow. The plants were born to grow, that’s their nature. But to thrive they require fertile soil. That’s essential. And as a home gardener, ensuring the soil’s fertility is my responsibility.

Gardening is not just a hobby I love, it’s also one of my favorite metaphors for raising children. The connection is beautifully exemplified by a German word for a group of children learning and growing: kinder garten.

The kids will grow, but they rely on us to provide them with fertile soil.

And so we do our best. We cultivate a nurturing environment, providing them with a warm and cozy bed to sleep in. We diligently weed out negative influences, ensuring their growth is not hindered. Just as we handle delicate plants and nurture the soil, we handle them with gentle care, aware of their tenderness. And of course, we try to root them in a family and community that radiates love onto them as the sun radiates sunshine

If we tend to the soil, the kids will thrive.

Well, almost. The kids will only flourish if we just add one more thing: rain.

Without rain, a garden cannot thrive. While individuals can irrigate a few plants during short periods without rainfall, gardeners like us can’t endure months or even weeks without rain. Especially under the intense conditions of summer heat and sun, our flowers and vegetables struggle to survive without rainfall. The rain is invaluable and irreplaceable.

As the rain comes and goes throughout the spring and summer, it saturates the entire garden bed, drenching the plants and the soil surrounding them. The sheer volume of rainwater is daunting to replicate through irrigation systems; attempting to match the scale of rainwater is financially burdensome. Moreover, rain possesses a gentle touch and a cooling effect. It nourishes the plants more effectively than tap water.

For all these reasons, rain is not something we merely hope for or ask for - rain is something we fervently pray for.

It's incredibly easy to overlook and take for granted the rain. It arrives and departs, quietly watering our garden when we least expect it. Rain can easily blend into the backdrop, becoming an unscheduled occurrence that simply happens as a part of nature's course.

When we harvest cherry tomatoes, basil, or bell peppers, a sense of pride and delight fills us as we revel in the fruits of our labor. The harvest brings immense satisfaction and a deep sense of pride, even if our family’s yield is modest and unassuming.

As we pick our cucumbers, pluck our spinach, or uproot our carrots, it rarely occurs to me to credit the rain. And yet, without the rain, our garden simply could not be.

In the lives of our children and within our communities, teachers serve ASC the rain. And by teachers, I mean a wide range of individuals. I mean the educators in elementary, middle, and high schools. I mean the pee-wee soccer coaches. I mean the Sunday school volunteers. I mean the college professors engaging in discussions on derivatives or the Platonic dialogues during office hours. I mean the early childhood educators who infuse dance parties into lessons on counting to ten and words beginning with the letter "A".

I mean the engineer moms, dads, aunts, and uncles who coach FIRST Robotics, or the recent English grads who dedicate their evenings to tutoring reading and writing. I mean the pastors and community outreach workers showin’ up on the block day in and day out. I mean the individuals running programs about health and nutrition out of their cars. I mean the retired neighbors on their porch who share stories of their world travels and become cherished bonus grandparents. I mean the police officers and accountants who serve as Big Brothers and Big Sisters despite having no obligation to do so.

I mean them all and more. These people, these teachers, are the rain.

They find a way to summon the skies and shower our kids with nourishing, life-giving rain. As a parent and a gardener nurturing the soil in which children are raised, I cannot replicate the rain that teachers provide. Without them, our children simply could not flourish.

Candidly, this is also a personal truth. I have greatly relied on and benefited from numerous teachers throughout my life. It has all come full circle for me as I've embraced the roles of both a parent and a gardener. Witnessing our children learn, grow, and thrive under the guidance of teachers has been a humbling revelation. I've come to realize that without teachers, my own growth and development would not have been possible. Without teachers, I simply would not be.

This time of year is brimming with graduations - whether they're from high schools, colleges, or even from Pre-K like our oldest just graduated from this weekend. Much like the bountiful harvest, it is a time for joyous celebration. Our gardens have yielded fruit, and we should take pride in our dedicated efforts.

But in this post, I also wish to honor all of the different types of teachers out there. They have been the gentle, nurturing rain - saturating the soil and fostering a fertile environment for our children to flourish.

Thank you, teachers, for everything you do and have done - for me, for our three sons, and for all children. We have all yearned for the rain to drench our gardens, and you have made it pour.

Photo by June Admiraal on Unsplash

The parenting cheat code(s)

The keys are sleep and paying attention. So obvious, but so elusive.

In retrospect, it seems so obvious that sleep and paying attention are crucial. If parenting were a video game, these would be the two cheat codes.

First, there’s plenty of data out there now that affirms how important sleep is. But as parents, we already know this, intimately, from lived experience. It’s obvious. When I don’t sleep enough, I am cranky and short-tempered. When the kids don’t sleep enough they are cranky and short-tempered. When we sleep, it’s a night and day difference—our household functions so much better when we sleep.

And then there’s paying attention. Again, there’s lots of data that emphasizes the importance of intimate relationships and being deeply connected to others. As parents, we also know this so well from lived experience. How many times a day have you heard, “Watch this, Papa”, “Papa, look at me in my pirate ship”, or worst of all, “Can you stop looking at your phone, Papa?”

When kids aren’t paid attention to, they literally scream for it. They fight to be loved and paid attention to, as they should—cheat code.

And as I’ve reflected on it over the years, these seem to be cheat codes for much more than parenting. It’s as if sleep and paying attention in the moment are cheat codes for a healthy, happy, and meaningful life.

In marriage, we are better partners and more in love when we sleep and pay attention. At work - sleep and paying attention boost performance and build high-performing teams. In friendships, the cheat codes still apply. In spiritual life, it’s the same thing. Sleep and paying attention are cheat codes.

And still, I almost blew it. I messed up for the first few years of Bo’s life. I didn’t get enough sleep. And I was too obsessed with work to pay attention him, fully, when I was home. I often missed stories and tuck-ins. My mind was itching to scratch off items on my to-do list and obsessing over the man I wanted to become in the eyes of others.

And the worst part, the one that makes me want to just…retreat, and trade a limb if I could, is that I remember so little of him as a newborn. I don’t remember how he laughed and giggled at 9 months old, barely at all. I don’t remember more than a handful of games we played together, maybe just peek-a-boo and “foot phone”. Damn, I am so sad, and weeping, as I pen this. I was there, but I still missed out.

I want so badly, for the man I am now to be baby Bo’s papa. Because at some point in the past two years, with a lot of help, I figured this out. I figured out the cheat codes—but, my tears cannot take me back. I have no time machine, no flux capacitor. What’s done is done. Damn.

The only consolation I have is that it didn’t take me longer. If I had lived my whole life not sleeping or paying attention—to Robyn, to our sons, to friends and family, or even just walking in the neighborhood and appreciating the trees—I’d probably pass from this world a miserable man with irreconcilable regret and guilt.

Right now, Bo, Myles, and Emmett, you are 5, 3, and 1 years old respectively. Maybe one day you’ll come across this post. Maybe I’ll be alive when you do—I hope so. Or maybe I’ll have gone ahead already, I don’t know.

But if you’re reading this one day, I am so deeply sorry that I messed up, and it took me years to figure this out—to start using these cheat codes I guess you could say. I apologize about this, especially to you Robert. I wasn’t fully there for you in your first 2-3 years.

I hope you all can forgive me. I am not perfect, but I’ve gotten better, and I’m still trying. I hope that by sharing this with you, you can avoid the same mistakes I made.

Photo by Lucas Ortiz on Unsplash

Fatherhood and The Birmingham Jail

To break the cycle, I must engage in self-purification that results in direct action.

Bo tells me what’s on his mind and heart, when it’s just him and I remaining at the dinner table. It’s as if he’s waiting for us to be alone and for it to be quet, and then, right then in that instant he drops a dime on me.

“Today at school, Billy kicked me, Papa.”

This time, thank God, I met him where he was instead of trying to fix his problems.I asked if he was okay, which he was. I passed a deep breath, silently, as I remembered that this is the way of the world - there are good kids that still hit and kick, and there are bullies, and that on the schoolyard stuff does happen. This, I begrudgingly admit to myself, is normal - even though it’s not supposed to happen to my kid.

So I started to ask Bo questions, trying my best to keep my anger from surfacing and making him feel guilty for something he could not control.

Bo, has learned how we do things in our family, what we believe. And in our family, we have strong convictions around nonviolence. He was sad, but he told me that he didn’t hit back. He didn’t meet violence with violence. This is my son, I thought.

I told him how strong he was, and how much strength it takes to not meet a kick with a kick; how strong a person has to be to not retaliate. I said he should be proud of himself, and that I was proud too.

But as we continued, I realized just how much like me, unfortunately, he really is. It also takes strength, I added, to draw a boundary. It takes so much strength to say something like, “I want to be friends with you, but if you continue to kick me, I will not.” It takes so much strength to confront a bully, even an unintentional one.

I talked Bo through the idea of boundaries and how to draw them as best I could. It made him visibly nervous - his five year old cheeks admitting nervous laughter as he tried to change the subject with talk of monkeys and tushys. Boundaries are so hard for him. He really is my son, I thought.

Boundaries have always been hard for me. I haven’t been able to draw them, to say no. They still are. For so long, I couldn’t keep my work at work. I haven’t been able to advocate for my own growth in any job to date or to reject an undesirable project which was unfairly assigned. When a dominating person tries to take and take, I may not roll over, but I don’t challenge them either.

My instinct to please others is so instinctual, I hardly ever know I’m doing it. This inability to draw boundaries is my tragic flaw.

One of my core beliefs about fatherhood is on this idea of breaking the cycle. I think there’s one core sin within me, maybe two, that I can avoid passing on. For me this is the one. This inability to draw boundaries and please others is what I want to break from our linage for all future generations. This is the flaw that I want to disappear when I die. Even before our sons arrived, I promised myself, this ends with me.

As I searched for answers and wisdom in the days that followed, my mind went to Dr. King and the ideas of nonviolence articulated by him and his contemporaries, like Gandhi, who were the only heroes outside of my family that I ever truly had.

I remembered this passage, from his 1963 Letter from a Birmingham Jail (emphasis added is my own):

In any nonviolent campaign there are four basic steps: collection of the facts to determine whether injustices exist; negotiation; self purification; and direct action. We have gone through all these steps in Birmingham. There can be no gainsaying the fact that racial injustice engulfs this community. Birmingham is probably the most thoroughly segregated city in the United States. Its ugly record of brutality is widely known. Negroes have experienced grossly unjust treatment in the courts. There have been more unsolved bombings of Negro homes and churches in Birmingham than in any other city in the nation. These are the hard, brutal facts of the case. On the basis of these conditions, Negro leaders sought to negotiate with the city fathers. But the latter consistently refused to engage in good faith negotiation.