Management Is Shifting From Leadership to Authorship

The same forces that disrupted the macroeconomy - like the internet and globalization - are making a similar disruption to the management of firms.

Harnessing this disruption is critical - to ensure the growth individual companies, but also for the continued progress of society at large.

It’s not that management is about to change at a fundamental level. What I’d propose is that it already has changed, but we just haven’t noticed it yet.

I predict that we will start noticing dramatic change in management practices within the next 10 years, because Covid-19 accelerated two trends that have been brewing for the previous quarter century: the digitization of internal firm communications, and, the adoption of Agile management practices.

What’s the fundamental change that’s happened in management?

In a sentence, the way I think about this fundamental change is that management is shifting its primary paradigm from “leadership” to “authorship”.

The paradigm of leadership is that there are leaders and followers. In a world oriented toward leadership, the manager is responsible for delivering results, making the efforts of the team exceed the sum of its parts, and aligning the team’s efforts so they contribute to the goals of the larger enterprise. The leader-manager takes on the role of structuring the vision, process, and the management structures for the team to hit its goals. The leader is directly responsible for their direct reports and accountable for their results. The leader-manager paradigm is effective in environments that call for centralization, control, consistency, and accountability.

The paradigm of authorship is that there are customers and needs to fulfill, that everyone is ultimately responsible for in their own way. In a world oriented toward authorship the manager is responsible for understanding a valuable need, setting a clear and compelling objective, and creating clear lanes for others to contribute. The author-manager takes on the role of finding the right objectives, communicating a simple and compelling story about them, and creating a platform for shared accountability rather than scripting how coordination will occur. The author-manager paradigm is effective in environments that call for dynamism, responsiveness, and multi-disciplinary problem solving.

This distinction really becomes clearer when thinking about the skills and capabilities critical to authorship. To be successful as an author-manager one must be incredibly good at really understanding a customer, and articulating how to serve them in an inspiring and compelling way. The author-manager has to create simple, cohesive narratives and share them. The author-manager needs to build relationships across an entire enterprise (and perhaps outside the firm) to bring skills and talents to a compelling problem, much as a lighting rod attracts lighting. The author-manager needs to create systems and platforms for teams to manage themselves and then step out of the way of progress. This set of capabilities is very different than the core MBA curriculum of strategy, marketing, operations, accounting, statistics, and finance.

In both paradigms, management fundamentals still matter. Both postures of management - leadership and authorship - require great skill, are important, and are difficult to do well. I don’t mean to imply that “leadership” is without value. The relative value of each, however, depends on the context in which they are being used. And for us, here in 2022, the context has definitely shifted.

How has the context related to the internal organizations of firms shifted?

In a sentence, firms are shifting from hierarchies to networks.

I’d note before any further discussion that this is idea of shifting from hierarchies to networks is not a new idea. General Stanley McChrystal saw this shift happening while fighting terrorist networks. Marc Andreessen and other guests on the Farnam Street Knowledge Project podcast also hint at this shift directly or indirectly. So do progressive thinkers on management, like Steven Denning. I’m not the first to the party here, but there’s some context I would add to help explain the shift in a bit more detail.

After the industrial revolution, as economies and global markets began to liberalize in the 20th Century, companies got big. Economies of scale and fixed cost leverage started to matter a lot. Multinationals started popping up. Globalization happened. Lots of forces converged and all these large corporations and institutions came into existence and needed to be managed effectively.

Hierarchical bureaucracies filled this need. In these hierarchical bureaucracies, tiers of leader-managers worked at the behest of a firm’s senior management team, to help them exert their vision and influence on a global scale. The vision and strategy were set at the top, and the layers of managers implemented this vision.

I think of it like water moving through a system of pipes In a hierarchy, it is the job of the executive team to create pressure, urgency, and direction and push that “water” down to the next layer. Then the next layer down added their own pressure and pushed the water down to the next layer, and so on, until the employees on the front line were coordinated and in line with the vision of the executive team. This was the MO in the 20th and early 21st Century.

A network operates quite differently, it functions on objectives, stories, and clearly articulated roles. In a network an author-manager sees a need that a customer or stakeholder has. Then, they figure out how to communicate it as an objective - with a clear purpose, intended outcome, measure for success, and rules of engagement for working together. This exercise is not like that of the hierarchy where the manager exerts pressure downward and aims for compliance to the vision. In a network what matters is putting out a clear and compelling bat signal, and then giving the people who engage the principles and parameters to self-organize and execute.

Both approaches - hierarchies and networks - are effective in the right circumstances. But a trade off surely exists: put briefly, the trade-off between hierarchies and networks is a trade-off between control and dynamism.

Why is this change happening?

In the 20th century, control mattered a lot. These were large, global companies that needed to deliver results. But then, digital infrastructures (i.e., internet and computing) started to make information to flow faster. Economic policies become more liberal so goods and people also started to flow faster. And all these changes led to consumers having more choice, information, and therefore more power. Again, this was not my idea, John Hagel, John Seeley Brown, Lang Davison, and Deloitte’s Center for the Edge articulated “The Big Shift” in a monumental report almost 15 years ago.

Here’s the top-level punchline: the internet showed up, consumers got a lot more power because of it, the global marketplace was disrupted, and firms started to have to be much more responsive to consumers’ needs. The trade-off between control and dynamism tilted toward dynamism.

What I’d suggest is that these same force that affected the global market also affected the inner world of firms. That influence on the firm is what’s tilting the balance from leadership and hierarchy to authorship and networks.

To start, digital infrastructures like the internet didn’t just change information flows in the market, it changed information flows inside the firm. Before, information had to flow through cascades of people and analog communication channels. The leader-manager layer of the organization was the mediator of internal firm communications. In the pre-digital world, there was no other way to transmit information from senior executives to the front-line - the only option was playing telephone, figuratively and literally.

But now, that’s different. Anyone in a company can now communicate with anyone else if they choose to. We don’t even just have email anymore. Thanks to Covid-19, the use of digital communication channels like Zoom, Slack, and MS Teams are widely adopted. We now have internal company social networks and apps that work on any smartphone and actually reach front-line employees. We have easy and cheap ways to make videos and other visualizations of complex messages and share them with anyone, in any language, across the world. Just like eCommerce retailers can circumvent traditional distribution channels and sell directly to consumers, people inside companies can circumvent middle managers and talk directly to the colleagues they most want to engage.

Now, more than ever, putting out a bat signal that attracts people with diverse skills and experience from across a firm to solve a problem actually can happen. Before, there was no other choice but to operate as a hierarchy - middle level managers were needed as go-between because direct communication was not possible or cheap. But now that’s different, any person - whether it’s the CEO or a front-line customer service rep - can use digital communication channels to interact with any other node in the firm’s network if they choose to.

I’ve lived this change personally. When I started as a Human Capital Consultant in 2009, we used to think about communicating through cascaded emails from executives, to directors, to managers, to front-line employees. Now, when I work on communicating strategy and vision across global enterprises, our small but mighty communications team works directly with front-line mangers who run plants and stores. We might actually avoid working through layers of hierarchy because it slow and our message ends up getting diluted anyway. Working through a network is better and faster than depending on a hierarchy to “cascade the message down.”

Agile management practices have also enabled the shift from hierarchies to network occur. Agile was formally introduced shortly after the turn of the 21st century as a set of principles to use in software development and project management. There’s lots of experts on Agile, SCRUM and other related methodologies, but what I find relevant to this discussion is that Agile practices allow teams to work more modularly and therefore more dynamically than typical teams. Working in two week sprints with a clear output scoped out, for example, makes it so that new people can more easily plug in and out of a team’s workflow.

What that means in practice is that the guidance, direction, accountability, and pressure of a hierarchy is no longer necessary to get work done. Teams with clarity on their customer, their intended outcome, and their objectives can manage work themselves without the need for centralized leadership from the focal point of a hierarchy. Agile practices allow networks of people to form, work, and dissolve fluidly around objectives instead of rigid functional responsibilities. Especially when you add in the influence of Peter Drucker’s Management by Objective in the 1950s and the OKR framework developed at Intel in the 1970’s, working in networks is now possible in ways that weren’t even 25 years ago. For the first time, maybe ever, large enterprises don’t absolutely need hierarchical management.

I lived this reality out when our team hosted an intern this summer. I was part of a team which was using Agile principles to manage itself. Our team’s intern was able to integrate into a bi-weekly sprint and start contributing within hours, rather than after days or weeks of orientation. Instead of needing a long ramp up and searching for a role, he just took a few analytical tasks at a sprint review and started running. Even though I’m biased as a true-believer of Agile, I was shocked at how easily he was able to plug in and out of our team over the course of his summer internship, and how quickly he was able to contribute something meaningful.

Even 20 years ago, this modular, networked way of working was much harder because nobody had invented it yet, or at a minimum these practices weren’t widely adopted. Now, these two ideas of Agile and OKR are baked into dozens, maybe hundreds, of software tools used by teams and enterprises all around the world. It’s not that these new, more network-oriented ways of working are going to hit the mainstream, they already have.

The adoption of digital communication tools and Agile practices inside firms has been stewing for a long time. Covid merely accelerated the adoption and the culture change that was already occurring.

And as if that wasn’t enough, the landscape could be entirely different a decade from now if and when blockchain and smart contracts emerge, further blurring the boundaries of the firm and it’s ecosystem. It’s not that management is going to shift, it already has, and it will continue to.

Why does it all matter?

I wrote and thought about this piece because I’ve observed some firms become more successful than their competitors, and I’ve observed some managers become more successful than their peers. I’ve been trying to explain why so I could share my observations with others.

And the simple reason is, some firms and some managers are embracing authorship and networks, while their less successful peers are holding tight to traditional leadership and hierarchy.

Managers who want to be successful act differently. If the world has become more dynamic, managers can’t stick with the same old posture of leadership and clutching the remnants of a hierarchical world. What managers have to do instead is lean into authorship and learn to operate effectively in networked ecosystems.

But I think the stakes are much larger than the career advancement and professional success of managers. What’s more significant to appreciate is the huge mismatch many organizations have between their management paradigm and their operating environment.

The way I see it, enterprises that are stuck in the 20th Century mindset of leadership and hierarchy rather than authorship and networks are missing huge opportunities to create value for their stakeholders. If you’re part of an organization that’s stuck in the past, prepare to be beat by those who’ve embraced authorship, networks, and agility.

But more than that, this mismatch prevents forward progress, not just for individual enterprises, but for our entire society. Management scholar Gary Hamel estimates this bureaucracy tax to be three trillion dollars.

For most people, thinking about management structure is burning and pedantic, but I disagree. Modernizing the practice of management is just as important as upgrading an enterprise’s information technology and doing so successfully leads to a huge windfall gain of value. To progress our society, we have to fix this mismatch so that the management practices deployed widely in the organizational world are the best possible approaches for solving the most critical challenges our teams, companies, NGOs, and governments face. I honestly don’t think it’s hyperbolic to say this: the welfare of future generations depends, in part, on us shifting management from leadership and hierarchy to authorship and networks.

To make faster progress - whether at the level of a team, a firm, or an institution - embracing this fundamental shift in management from leadership and hierarchy to authorship and networks is non-negotiable. Remember, it’s not that this shift is going to happen, it already has.

Photo from Unsplash, by @deepmind

Culture Change is Role Modeling

Lots of topics related to “leadership” are made out to be complicated, but they’re actually simple.

Culture change is an example of this phenomenon, it’s mostly just role modeling.

Probably 80% of “culture change” in organizations is role modeling. Maybe 20% is changing systems and structures. Most organizations I’ve been part of, however, obsess about changing systems instead of role modeling.

In real life, “culture change” basically work like this.

First, someone chooses to behave differently than the status quo, and does it in a way that others can see it. This role modeling is not complicated, it just takes guts.

Two, If the behavior leads to a more desirable outcome, other institutional actors take notice and start to mimic it.

This is one reason why people say “culture starts at the top.” People at the top of hierarchies are much more visible, so when they change their behavior, people tend notice. Culture change doesn’t have to start at the top, but it’s much faster if it does.

Three, if the behavior change is persistent and the institutional actors are adamant, they end up forcing the systems around the behavior to change, and change in a way that reinforces the new behavior. This is another reason why “culture starts at the top”. Senior executives don’t have to ask permission to change systems and structures, then can just force the people who work for them to do it.

If the systems and structure change are achieved, even a little, the new behavior then has less friction and a path dependency is created. A positive feedback loop is born, and before you know it the behvaior is the new norm. See the example in the notes below.

Again, this is not a complicated. Role modeling is a very straightforward concept. It just takes a lot of courage, which is why it doesn’t happen all the time.

A lot of times, I feel like organizations make a big deal about “culture change” and “transformation”. Those efforts end up having all these elaborate frameworks, strategies, roadmaps, and project plans. I’m talking and endless amount of PowerPoint slides. Endless.

I think we can save all that busywork. All we have to do is shine a light on the role models, or be a role model ourselves…ideally it’s the latter. The secret ingredient is no secret - culture change takes courage.

So If we don’t see culture change happening in our organization, we probably don’t need more strategy or more elaborate project plans, we probably just need more guts.

—

Example: one way to create an outcomes / metrics-oriented culture through role modeling.

Head of organization role models and asks a team working on a strategic project to show the data that justifies the most recent decision.

Head of organization extends role modeling by using data to explain justification when explaining decision to customers and stakeholders in a press conference.

Head of organization keeps role modeling - now they ask for a real-time dashboard of the data to monitor success on an ongoing basis.

Other projects see how the data-driven project gets more attention and resources. They build their own dashboards. More executives start demanding data-driven justifications of big decisions.

All this dashboard building forces the organization’s data and intelligence team to have more structured and standardized data.

What started as role modeling becomes a feedback loop: more executives ask for data, which causes more projects to use data and metrics, which makes quality data more available, which leads to more asks for data, and so on.

*Note - this example is not out of my imagination. This is what I saw happening because of the Mayor and the Senior Leadership Team at the City of Detroit during my tenure there.

If true, am I really a “leader”?

If I choose to shirk responsibility, what am I?

If I choose to…

…say “just give it to me” instead of teach,

…set a low standard so I don’t have to teach,

…blame them for not “being better”,

…blame them for my anger instead of owning it,

…let the outcome we’re trying to achieve remain unclear,

…keep the important reason for what we’re doing a secret,

…leave my own behavior unmeasured and unmanaged,

…set a high standard without being willing to teach,

…proceed without listening to what’s really going on,

…proceed without understanding their superpowers and motivations,

…withhold my true feelings about a problem,

…avoid difficult conversations,

…believe doing gopher work to help the team is “beneath me”,

…steal loyalty by threatening shame or embarrassment,

…move around 1 on 1 time when I get better plans,

…be absent in a time of need (or a time of quiet celebration),

…waffle on a decision,

…or let a known problem fester,

Am I really a “manager” or a “leader”? Can I really call myself a “parent”?

If I’ve shirked all the parts requiring responsibility, what am I?

To me all “leadership” really is, is taking responsibility. It’s the necessary and sufficient condition of it. The listed items I’ve prepared are just some examples of the responsibilities we can choose (or not) to take.

And, definitely, there are about 5 of those that I fail at, regularly. My hope is that by making these moments transparent, it will be more possible to make different choices.

We Need To Understand Our Superpowers

We need to take the time to understand our superpowers, as individuals or as an organization, so we have the best chance to create surplus.

Surplus is created when something is more valuable than it costs in resources. Creating surplus is one of the keys to peace and prosperity.

Surplus ultimately comes from asymmetry. Asymmetry, briefly put, is when we have something in a disproportionately valuable quantity, relative to the average. This assymetry gives us leverage to make a disproportionally impactful contribution, and that creates surplus.

Let’s take the example of a baker, though this framework could apply to public service or family life. Some asymmetries, unfortunately, have a darker side.

Asymmetry of…

…capability is having the knowledge or skills to do something that others can’t (e.g., making sourdough bread vs. regular wheat).

…information gives the ability to make better decisions than others (e.g., knowing who sells the highest quality wheat at the best price).

…trust is having the integrity and reputation that creates loyalty and collaboration (e.g., 30 years of consistency prevents a customer from trying the latest fad from a competitor).

…leadership is the ability to build a team and utilize talent in a way that creates something larger than it’s parts (e.g., building a team that creates the best cafe in town).

…relationships create opportunities that others cannot replicate (e.g., my best customers introduce me to their brother who want to carry my bread in their network of 100 grocery stores).

…empathy is having the deep understanding of customers and their problems, which lead to innovations (e.g., slicing bread instead of selling it whole).

…capital is having the assets to scale that others can’t match (e.g., I have the money to buy machines which let me grind wheat into flour, reducing costs and increasing freshness).

…power is the ability to bend the rules in my favor (e.g., I get the city council to ban imports of bread into our town).

…status is having the cultural cachet to gain incremental influence without having to create any additional value (e.g., I’m a man so people might take me more seriously).

We need to understand our superpowers

So one of the most valuable things we can do in organizational life is knowing the superpowers which give us assymetry and doing something special with them. We need to take the time to understand our superpowers, as individuals or as an organization, so we have the best chance to create surplus.

And once we have surplus - whether in the form of time, energy, trust, profit, or other resources - we can do something with it. We can turn it into leisure or we can reinvest it in ourselves, our families, our communities, and our planet.

—

Addendum for the management / strategy nerds out there: To put a finer point on this, we also need to understand how asymmetries are changing. For example, capital is easier to access (or less critical) than it was before. For example, I don’t know how to write HTML nor do I have any specialized servers that help me run this website. Squarespace does that for me for a small fee every month. So access to capital assets and capabilities is less asymmetric than 25 years ago, at least in the domain of web publishing.

As the world changes, so does the landscape of asymmetries, which is why we often have to reinvent ourselves.

There’s a great podcast episode on The Knowledge Project where the guest, Kunal Shah, has a brief interlude on information asymmetry. Was definitely an inspiration for this post.

Source: Miguel Bruna on Unsplash

Coaching Requires Dedicated, intensely Focused Time

The biggest error of coaching - not being intentional about it - can be avoided by dedicating real time to it.

People develop faster when they are coached well, but coaching doesn’t happen without intent. To be a better coach, start with making actual “coaching time” that is intentional and intensely focused.

First, as a manager, we must dedicate one-to-one time with whomever we are trying to coach. 30 minutes per week, used well, is enough.

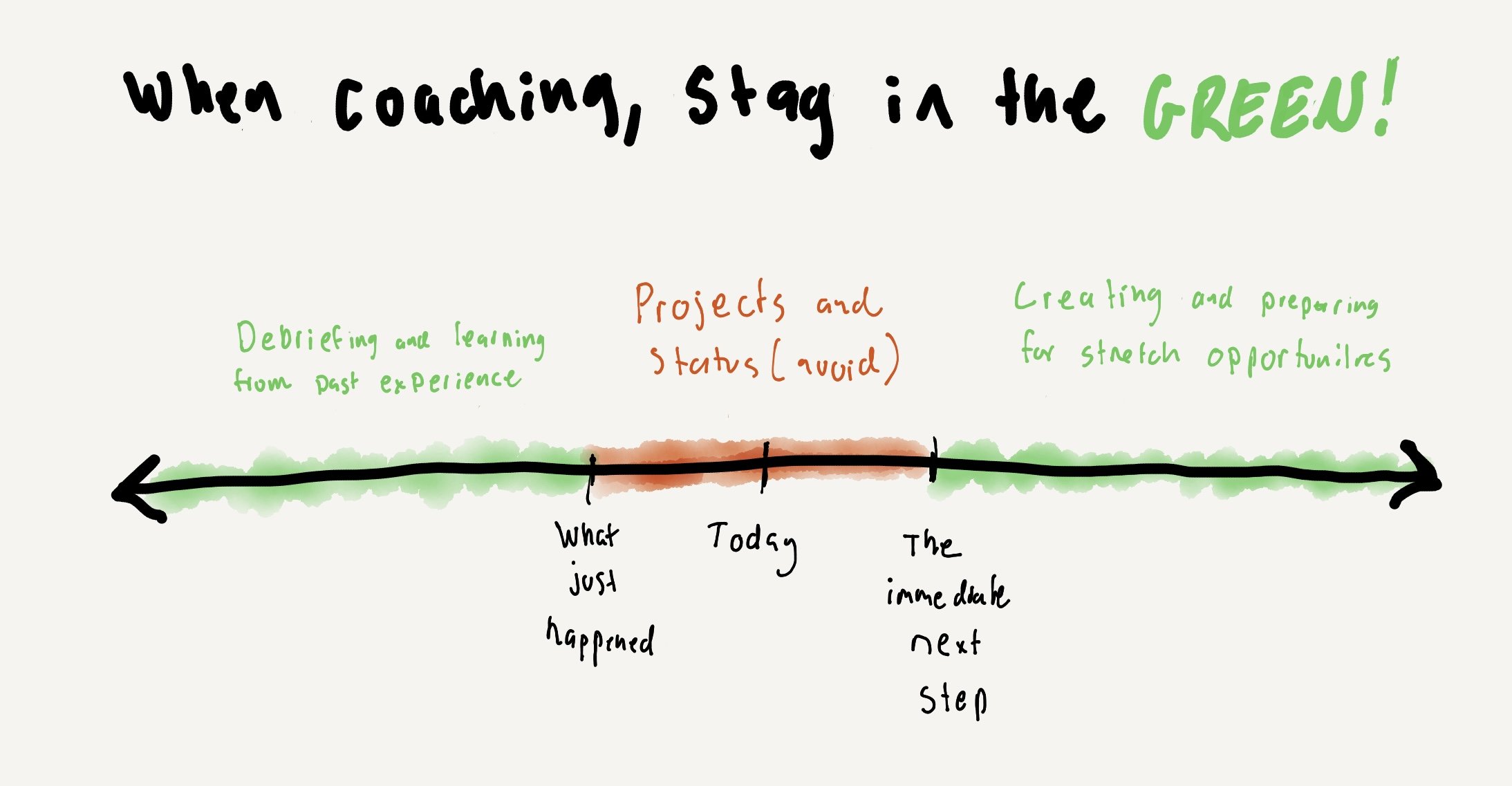

Second, that time can’t be about projects or status. It has to be spent on debriefing to glean learnings from past performance, or on how to create and prepare for future stretch opportunities.

Find a better way to manage status and project work than during a 1-1 and dedicate that time too and use it with intense focus. Personally, I like daily stand-ups from Agile/Scrum methodology and a once weekly full project review with the whole team.

Then, set a rule that during the dedicated time you will not talk about project status or the daily grind of work. If you dedicate time and hold firm to that rule, you’ll end up having a productive coaching conversation. Here are four questions that I’ve found work well to structure a 30-minute coaching conversation.

On a scale of 1 to 100, what percent of the impact you think you could be making are you actually making? (2-4 minutes)

Compared to last week, is your rate of growth accelerating, decelerating, or about the same? (2-4 minutes)

What do you want to talk about? (20-25 minutes)

What’s something I can do to help you feel respected and supported? (2-4 minutes)

This concept applies broadly: whether it’s coaching our team at work, our kids, our students, a volunteer group we’re part of, or co-coaching our marriage together with our partner, we must dedicate and focus the time. In my experience, the results of that dedicated time are exponential after just a few weeks.

Good Managers Produce Exceptional Teams

This is an OKR-based model to define what a good manager actually produces. It’s hard to be good at something without beginning with the end in mind, after all.

The difference between a good manager and a bad one can be huge.

Good managers make careers while others break them. Good managers bring new innovations to customers while others quit. Good managers find a way to make a profit without polluting, exploiting, or cheating while others cut corners. Good managers find ways to adapt their organizations while others in the industry go extinct.

But it’s almost impossible to be good at something without defining what success looks like. As the saying goes, “begin with the end in mind.”

This is one model for the results a good manager takes responsibility to produce.

What would you add, subtract, or revise? My hope is that by sharing, all of us that are committed to being good managers get better faster.

Objective: Be a Good Manager

Key Results:

Talent of each team member is fully utilized

Develop team members enough to be promoted

Team has and utilizes diverse perspectives

Team delivers measurable results on an important business objective

Team is trusted by internal and external customers

Team and all stakeholders are clear on on the why, what, how, when, and intended result of our work

Whole team feels supported and respected

Team stewards resources (time, money, etc.) effectively

To build a great team, get specific

To scale impact, every team leader has to build their team. Building a team is hard, but it’s not complicated.

To set us up for success, they key thing to do is get specific about the role, and the top 2-3 things we can’t compromise on in a candidate.

Building a team is hard, but it doesn’t have to be complicated.

What I’ve learned when trying to build teams (whether serving on hiring committees, recruiting fraternity pledges, or volunteer board members) is that most of the time we’re not specific enough.

To build a great team, we can’t just fill the role with a body. We can’t count on the perfect candidate either - there are no unicorns. Instead, we should be clear about the role, and the attributes that we can and cannot compromise on.

Here’s a video with a tool / mental model on how to actually do that.

Learning to Win Ugly

Learning how to win ugly is an essential skill. And yet, I feel like the world has conspired to keep me from learning it.

What it takes to “win” is different than what it takes to “win ugly.” In sports what it means to win ugly can be something like:

Winning a close, physical game

Winning in bad weather or difficult conditions

Winning without superstars

Winning after overcoming a deficit or when your team is particularly outmatched

Winning by just doing what needs to be done, even if it’s not fancy or flashy

But winning ugly is also a useful metaphor outside sports:

In a marriage: keeping a relationship alive during adversity (e.g., during a global pandemic) or after a major loss

In parenting: staying patient during bedtime when a child is overtired and throwing a tantrum

In public service: improving across-the-board quality of life for citizens after the city government, which has been under-invested in for decades, goes through bankruptcy (I’m biased because I worked in it, but the Duggan Administration Detroit is my thinly veiled example here)

At work: finding a way to reinvent an old-school company that’s not large, prestigious, or cash-infused enough to simply buy “elite” talent

The point of all these examples is to suggest that it’s easier to succeed when circumstances are good, such as when: there’s no adversity, the problem and solution are well understood, you’re on a team of superstars, or you’re flush with cash. It’s something quite different to succeed when the terrain is treacherous.

I’ve been thinking about the idea of winning ugly lately because as a parent, the fee wins we’ve had lately have been ugly ones.

Generally speaking, I’ve come to believe that winning ugly is important because it seems like when the stakes are highest and failure is not an option - like during a global pandemic, or when a city has unprecedented levels of violent crime, or when the economy is in free fall, or a family is on the verge of collapse after a tragedy - there’s usually no way to win except winning ugly.

I’d even say winning ugly is essential - because every team, family, company, and community falls upon hard times. In the medium to long run, it’s guaranteed. But honestly, I don’t think most people look at this capability when assessing talent for someone they’re interviewing for a job, or even when filling out their NCAA bracket.

Moreover, as I’ve reflected on it, I’ve realized that my whole life, I’ve been coached, actively, to avoid ugly situations. I was sent to lots of enrichment classes where I had a lot of teachers and extra help to learn things (not ugly). I had easy access to great facilities, like tennis courts, classrooms, computer labs, and weight rooms (not ugly). I was encouraged to take prep classes for standardized tests (not ugly). I was raised to think that the way to achieve dreams was to attend an Ivy League school (not ugly).

If I did all these things I could get a job at a prestigious firm that was established, and make a lot of money, and live a successful life.

What I’ve realized, is that this suburban middle class dream depends on putting yourself in ideal situations. The whole strategy hinges on positioning - you work hard and invest a lot so you can position yourself for the next opportunity. If you’re in a good position, you’re more likely to succeed, and therefore set yourself up for the next thing, and so on.

If you don’t think winning ugly matters, this is no problem. But if you do believe it’s important to know how to pull through when it’s tough, the problem is that the way you learn to win ugly is to put yourself into tough situations, not easy ones. The problem with how I (and many of us) were raised is that we didn’t have a lot of chances to learn to win ugly.

I, for example, learned to win ugly in city government, at the Detroit Police Department…in my late twenties and thirties.

There, we caught no breaks. Every single improvement in crime levels we had to scrap for. Every success seemed to come with at least 2 or 3 obstacles to overcome. We didn’t have slush fund of cash for new projects. We didn’t have a ton of staff - even my commanding officers had to get in the weeds on reviewing press briefings, grant applications, or showing up to crime scenes. Just about any improvement I was part of was winning ugly.

By my observation here’s what people who know how to win ugly do different:

No work is beneath anyone: if you’re winning ugly, even the highest ranking person does the unglamourous work sometimes. You can’t win ugly unless every single person on the team is willing to roll up their sleeves and do the quintessential acts of diving for loose balls, grabbing the coffee, sweeping the floor, or fixing the copy machine.

Unleashing superpowers: If you are trying to win ugly, that means you have to squeeze every last bit of talent and effort out of your team. That requires knowing your team and finding ways to match the mission with the hidden skills that they aren’t using that can bring disproportionate results. People who win ugly doesn’t just look for hidden talents, they look for superpowers and bend over backwards to unleash them.

Discomfort with ambiguity: A lot of MBA-types talk about how it’s important to be “comfortable with ambiguity”. That’s okay when you have a lot of resources and time. But that doesn’t work if you’re trying to win ugly. Rather, you move to create clarity as quickly as possible so that the team doesn’t waste the limited time or resources you have.

Pivot hard while staying the course: When you’re winning ugly, you can’t stick with bad plans for very long. People who have won ugly know that you don’t throw good money after bad, and you change course - hard if you need to - once you have a strong inclination that the mission will fail. At the same time, winning ugly means sticking with the game plan that you know will work and driving people to execute it relentlessly. Winning ugly requires navigating this paradox of extreme adjustment and extreme persistence.

Tap into deep purpose: Winning ugly is not fun. In fact, it sucks. It’s really hard and it’s really uncomfortable. Only people who love punishment would opt to win ugly, 99% of the time you win ugly because there’s no other way. Because of this reality, to win ugly you have to have access an unshakeable, core-to-the-soul, type or purpose. You have to have deep convictions for the mission and make them tremendously explicit to everyone on the team. That’s the only way to keep the team focused and motivated to persist through the absolute garbage you have to sometimes walk through to win ugly. Teams don’t push to win when it’s ugly if their motivation is fickle.

Doing the unorthodox: People who can win pretty have the luxury of doing what’s already been done. People who win ugly don’t just embrace doing unconventional things, they know they have no other choice.

Be Unflappable: I’ve listed this list because it’s fairly obvious. When it’s a chaotic environment, people who know how to win ugly stay calm even when they move with tremendous velocity. This doesn’t necessarily mean they don’t get angry. In my experience, winning ugly often involves a lot of cursing and heated discussions. But not excuses.

Sure, I think it’s possible to use this mental model when forming a team or even when interviewing to fill a job: someone may have a lot of success, but can they win ugly?

But more than that, I am my own audience when writing this piece. I don’t want to be the sort of husband, father, citizen, or professional that only succeeds because of positioning. At the end of my life, I don’t want to think of myself as someone who only succeeded because I avoided important problems that were hard.

And, I don’t want to teach our sons to win by positioning. I want them to succeed and reach their dreams, yes, but I don’t want to take away their opportunity to build inner-strength, either. This is perhaps the most difficult paradox of parenting (and coaching at work) that I’ve experienced: wanting our kids (or the people we coach) to have success and have upward mobility, but also letting them struggle and fail so they can learn from it, and win ugly the next time.

Bad Managers May Finally Get Exposed

If we’re lucky, the Great Resignation may only be the beginning.

Hot take: the shift to remote work will finally expose bad managers, and help good managers to thrive.

If I were running an enterprise right now, I’d be doubling down HARD on improving management systems and the capabilities of my organization’s leaders. Why?

Because bad management is about to get exposed.

This is merely a prediction, but even with all the buzz about the “Great Resignation” I actually think most organizations - even ones that are actively investing in “talent” - are underrating the impact of workforce trends that have started during the pandemic. The first order effect of these trends manifests in the Great Resignation (attrition, remote work, work-life balance) but I think the second-order effects will reverberate much more strongly in the long-run.

Here’s my case for why.

A fundamental assumption a company could make about most workers, prior to the pandemic, was that they were mostly locked in to living and working in the same metro or region as their office location. Now, hybrid and fully remote work is catching on, and this fundamental assumption of living and working in the same region is less true than it was three years ago.

This shift accelerates feedback loops around managers in two ways. One, it lowers the switching costs and broadens the job market for the most talented workers. Two, it opens up the labor pool for the most talented managers - who can run distributed teams and have the reputation to attract good people.

I think this creates a double flywheel, which creates second order effects on the quality of management. If this model holds true in real life, good managers will thrive and create spillover effects which raise the quality of management and performance in other parts of their firms. Bad managers, on the contrary, will fall into a doom loop and go the way of the dinosaur. Taken together, I hope this would raise the overall quality of managers across all firms.

Here’s a simple model of the idea:

Of course, these flywheels most directly affect the highest performing workers in fields which are easily digitized. But these shifts could also affect workers across the entire economy. For example, imagine a worker in rural America or a lesser known country, whose earnings are far below their actual capability. Let’s say that person is thoughtful and hard working, but is bounded by the constraints of their local labor market.

Unlike before, where they would have to move or get into a well known college for upward mobility - which are both risky and expensive - they can now more easily get some sort of technical certification online and then find a remote job anywhere in the world. That was always the case before, but the difference now is that their pool of available opportunities is expanded because more firms are hiring workers into remote roles - there’s a pull that didn’t exist before.

Here’s what I think this all means. If this prediction holds true, I think these folks would be the “winners”:

High-talent workers (obviously): because they can seek higher wages and greater opportunities with less friction.

High-talent managers: because they are better positioned to build and grow a team; high-talent workers will stick with good managers and avoid bad ones.

Nimble, well-run, companies: companies that are agile, flexible, dynamic, flat, (insert any related buzzword here) will be able to shape teams and roles to the personnel they have rather than suffocating potential by forcing talented people into pre-defined roles that don’t really fit them. A company that can adjust to fully utilize exceptional hires will beat out their competitors

Large, global, companies: because they have networks in more places, and are perhaps more able to find / attract workers in disparate places.

Talent identification and development platforms: if they’re really good platforms, they can become huge assets for companies who can’t filter the bad managers and workers from the good. Examples could be really good headhunters or programs like Akimbo and OnDeck.

All workers: if there are fewer bad managers, fewer of us have to deal with them!

And these are the folks I would expect to be the “losers”:

Bad managers: because they’re not only losing the best workers, they’re now subject to the competitive pressure of better managers who will steal their promotions.

Companies with expensive campuses: because they’re less able to woo workers based on facilities and are saddled with a sunk cost. Companies feeling like they have to justify past spend will adjust more slowly - ego gets in the way of good decisions, after all.

Most traditional business schools: because teaching people to manage teams in real life will actually matter, and most business schools don’t actually teach students to manage teams in real life. The blueboods will be able to resist transformational change for longer because their brands and alumni connections will help them attract students for awhile. But brands don’t protect lazy incumbents forever.

This shift feels like what Amazon did to retailers, except in the labor market. When switching costs became lower and shelf space became unlimited, retailers couldn’t get by just because they owned distribution channels and supply chains. Those retailers resting on their laurels got exposed, because consumers - especially those who had access to the internet and smartphones - gained more power.

And two things happened when consumers gained more power: some retailers (even large ones) vanished or became much weaker, and, the ones that survived developed even better customer experiences that every consumer could benefit from. It’s not a perfect analogy because the retail market is not exactly the same as the labor market, but switch “consumers” out with “high-talent workers” and the metaphor is illustrative.

Of course, a lot of things must also be true for this prediction to hold, such as:

We don’t enter an extended recession, which effectively ends this red hot labor market

Some sort of regulation doesn’t add friction to remote workers

Companies and workers are actually able to identify and promote good managers

Enough companies are actually able to figure how to manage a distributed workforce, and don’t put a wholesale stop to remote work

I definitely acknowledge this is a prediction that’s far from a lock. But I honestly see some of these dynamics already starting. For example…

The people that I see switching jobs and getting promoted are by and large the more talented people I know. And, I’m seeing more and more job postings explicitly say the roles can be remote. And, I see more and more people repping their friends’ job postings, which is an emerging signal for manager quality; I certainly take it seriously when someone I know vouches for the quality of someone else’s team.

So, I don’t know about y’all, but I’m taking my development as a manager and my reputation as a manager more seriously than I ever have. If you see me ask for you to write a review about me on LinkedIn or see me write a review about you, you’ll know why! I definitely don’t want to be on the wrong side of this trend, should it happen - you probably don’t.

Bad managers, beware.

Conflict resolution can be baked into the design of our teams, families

In hindsight, approaching organizational life - whether it’s in our family, marriage, our work, or our community groups - with the expectation that we’ll have conflict is so obviously a good idea. If we’re intentional, we can design conflict resolution into our routines and make our relationships and teams stronger because of it.

In our family, there are no small lies.

So when our older son (Bo) lied about knowing where our younger son’s (Myles) favorite-toy-of-the-week was, we didn’t take it lightly. He went to “the step” where I directed him to stay for 10 minutes.

“Think about the reason why you lied. I want to know why. We’re going to talk about it over lunch.”

“But papa…”

“You’re a good kid. But lying is unacceptable in this family. We’re going to talk about it over lunch.”

It turns out, Myles did not treat Bo well the previous night. The two of them recently started sharing a room (which they love and they get along great), and Myles was talking loudly and preventing his big brother from sleeping.

Bo, now four, was not happy about this. And even though Bo loves his little brother dearly - they’re best buds, thank goodness - his frustration manifested by taunting Myles about the toy keys, and lying about knowing where they were.

As we talked over lunch, the real problem became clear, lying was merely a symptom. Bo was angry about being mistreated by his little brother. What our lunch became was not an interrogation about why Bo lied, but a expression of feelings and reconciliation between brothers. Our scene was roughly like this:

“Bo, I think I understand why you lied about the toy keys. When someone does something we don’t like, we have to talk to them about it. I know it’s hard. Let me help you work this out with Myles. Could you tell Myles how you felt?”

“Sad.”

“Why?”

“Because you were talking loud and I couldn’t sleep.”

“What would you like him to do to make it right with you?”

“Don’t bother me when I’m trying to sleep, Myles.”

“Can you both live with this and say sorry?”

“Okaaayy…”

Which got me to thinking - this happens in organizational life all the time.

Intentionally or not, we get into conflicts with others. More often than not, the conflict brews until it spills out into an act of aggression. Rarely, in our organizational worlds, is conflict handled openly or proactively.

It’s understandable why it plays out this way Conflict is hard. Admittedly, my default - like that of most humans - is to avoid dealing with all but the most egregious of conflicts and letting things resolve on their own. Stopping everything to say, “hey, I’ve got a problem” is incredibly uncomfortable and difficult. Basically nobody likes being that guy.

It’s MUCH easier to pretend everything is fine, even though it’s usually a bad choice over the long-run. This tendency is unsurprising; it’s well understood that humans prefer to avoid short term pain, even if it means missing out on long-term gain.

But, we can design our organization’s practices to manage this cognitive bias. We can build pressure release valves into our routine, where it’s expected that we talk about conflict because we acknowledge up front that conflict is going to occur.

In our family, we’re experimenting with our dinner routine, for example. We shared with our kids that we’ll take a few minutes at the beginning of our meal to talk about what we appreciated about other members of the family, and share any issues that we’re having.

We had a moment like this with our kids:

“We all make mistakes, boys, because we’re all human. It’s expected. We’re going to talk about what’s bothering us before we get really sad and angry with each other.”

In hindsight, approaching organizational life - whether it’s in our family, marriage, our work, or our community groups - with the expectation that we’ll have conflict is so obviously a good idea. Conflict doesn’t have to be a bug, it can be a feature, so to speak. If we’re intentional, we can design conflict resolution into our routines and make our relationships and teams stronger because of it.

I didn’t realize it, but this design principle has been part of my organizational life already. The temperature check my wife and I do every Sunday is centered around it.

Even my college fraternity’s chapter meetings tapped into this idea of designing for peace. The last agenda item before adjournment was “Remarks and Criticism”, where everyone in the entire room, even if a hundred brother were present, had the chance to air a grievance or was required to verbally confirm they had nothing further to discuss.

The best part is, this “design” is free and really not that complicated. It could easily be applied in many ways to our existing routines:

Might we start every monthly program update by asking everyone, including the executives, to share their shoutouts and their biggest frustration?

Might every 1-1 with our direct reports have a standing item of “time reserved to squash beefs”?

Might part of our mid-year performance review script be a structured conversation using the template, I felt _______, when _________, and I’d like to make it right by _______?

Might the closing item of every congressional session be a open forum to apologize for conduct during the previous period and reconcile?

It might be hard to actually start behaving in this way (again, we’re human), but designing for peace is not complicated.

If you have a team or organizational practice that “designs” for peace and conflict resolution, please do share it in the comments. If you prefer to be anonymous, send me a direct message and I’ll post it on your behalf.

Sharing different practices that have worked will make organizational life better for all of us.

Diversity: An Innovation and Leadership Imperative

I was listening to a terrific podcast where Ezra Klein interviewed Tyler Cowen. And Tyler alluded to how weird ideas float around more freely these days - presumably because of diversity, the internet, social media, etc.

I think there’s a lot of implication for people who choose to lead teams and enterprises. How they manage and navigate teams with radically more diversity seems to be a central question of leadership today.

If you have any insights on how to operate in radically diverse environments, I’m all ears. Truly.

The US workforce is more diverse and educated than previous decades. And it’s getting more diverse and educated. This is a fact.

This transformation toward diversity is a big challenge. Because as any parent knows, a diversity of opinions leads to deliberation and friction. Managing diverse organizations is really, really hard - whether it’s a family, a volunteer organization, or a team within a large enterprise.

I’ve seen leaders respond to diversity in one of four ways:

Tyranny is fairly common. If you don’t want to deal with diversity, a leader can just suppress it - either by making their teams more homogenous or shutting down divergent ideas. The problem here is that coercive teams can rarely sustain high performance for extended periods of time, especially when the operating environment changes. Tyrannical leaders exterminate novel ideas, so when creative ideas are needed to solve a previously unseen problem, they struggle. Tyranny is also terrible.

Conflict avoidance is also fairly common. These are the teams that have diversity but don’t utilize it. On these sorts of teams, nobody communicates with candor and so diverse perspectives are never shared and mediated - they’re ignored. As a result, decisions are made slowly or never at all because real issues are never discussed. By avoiding the friction that comes with diverse perspectives, gridlock occurs.

Another response is polarization. Environments of polarization are unmediated, just like instances of conflict avoidance. But instead of being passive situations, they are street fights. In polarized environments, everyone is a ideologue fighting for the supremacy of their perspective, and nobody is there to meditate the friction and make it productive. Similar to conflict avoidance, polarization also leads to gridlock. I don’t often see this response to diversity in companies. But it seems a common phenomenon, at present, in America’s political institutions.

What I wish was more common was productive mediation of diversity. Something magical happens when a diverse-thinking group of people gets together, focuses on a novel problem, candidly shares their perspectives, and then tries to solve it. Novel insights emerge. Divergent ideas are born. New problems are solved. A more common word for this phenomenon is “innovation”.

It seems to me a central question in leadership of organizations today, maybe THE central question of leadership today is “how to do you respond to diversity?” Because, as I mentioned and linked to above - the workforce has become more diverse and more educated. Which means the pump is primed for lots of new, weird ideas and lots of conflict within enterprises.

Leaders have to respond to this newfound diversity. And whether they respond with tyranny, conflict avoidance, polarization, or productive mediation matters a great deal.

I wanted to share this thought because I think this link is often missed. Leadership is rarely cast as a diversity and innovation-management challenge, and diversity is usually cast as an inclusion and equity issue rather than as an innovation and leadership imperative.

The types of questions asked an interviews are a good bellwether for whether enterprises have understood the nuance here:

A traditional way to assess leadership: “Tell me about a time you set a goal and led a team to accomplish it.”

A diversity and innovation-focused way to assess leadership: “Tell me about a time you brought a team with diverse perspectives together and attempted to achieve a breakthrough result.”

The person who has a good answer to question one is not necessarily someone who has a good answer to question two, or vice versa. The difference matters.

High Standards Matter

Organizations fail when they don’t adhere to high standards. Creating that kind of culture that starts with us as individuals.

I’ve been part of many types of organizations in my life and I’ve seen a common thread throughout: high standards matter.

Organizations of people, - whether we’re talking about families, companies, police departments, churches, cities, fraternities, neighborhoods, or sports teams - devolve into chaos or irrelevance when they don’t hold themselves to a high standard of conduct. This is true in every organization I’ve ever seen.

If an organization’s equilibrium state is one of high standards (both in terms of the integrity of how people act and achieving measurable results that matter to customers) it grows and thrives. If its equilibrium is low standards (or no standards) it fails.

If you had to estimate, what percent of people hold themselves to a high standard of integrity and results? Absent any empirical data, I’ll guess less than 25%. Assuming my estimate is roughly accurate, this is why leaders matter in organizations. If individuals don’t hold themselves to high standards, someone else has to - or as I said before, the organization fails.

Standard setting happens on three levels: self, team, and community.

The first level is holding myself to a high standard. This is basically a pre-requisite to anything else because if I don’t hold myself to a high standard, I have no credibility to hold others to a high standard.

The second level is holding my team to a high standard. Team could mean my team at work, my family, my fraternity brothers, my company, my friends, etc. The key is, they’re people I have strong, direct ties to and we have an affiliation that is recognized by others.

To be sure, level one and level two are both incredibly difficult. Holding myself to any standard, let alone a high standard, takes a lot of intention, hard work, and humility. And then, assuming I’ve done that, holding others to a high standard is even more difficult because it’s really uncomfortable. Other people might push back on me. They might call me names. And, it’s a ton of work to motivate and convince people to operate at a high standard of integrity and results, if they aren’t already motivated to do so. Again, this is why (good) leadership matters.

The third level, holding the broader community to a high standard, is even harder. Because now, I have to push even further and hold people that I may not have any right to make demands of to a high standard. (And yes, MBA-type people who are reading this, when I say hold “the broader community” to a high standard, it could just as easily mean hold our customers to a high standard.)

It takes so much courage, trust, effort, and skill to convince an entire community, in all it’s diversity and complexity, to hold a high standard. It’s tremendously difficult to operate at this level because you have to influence lots of people who don’t already agree with you, and might even loathe you, to make sacrifices.

And I’d guess that an unbelievably small percentage of people can even attempt level three. Because you have to have a tremendous amount of credibility to even try holding a community to a high standard, even if the community you’re operating in is relatively small. Like, even trying to get everyone on my block to rake their leaves in the fall or not leave their trash bins out all week would be hard. Can you imagine trying to influence a community that’s even moderately larger?

But operating at level three is so important. Because this is the leadership that moves our society and culture forward. This is the type of leadership that brings the franchise to women and racial minorities. This is the type of leadership that ends genocide. This is the type of leadership that turns violent neighborhoods into thriving, peaceful places to live. This is the type of leadership that ends carbon emissions. This is the type of leadership, broadly speaking, that changes people’s lives in fundamental ways.

I share this mental model of standards-based leadership because there are lots of domains in America where we need to get to level three and hold our broader community to a high standard. I alluded to decarbonization above, but it’s so much more than that. We need to hold our broader community to a high standards in issue areas like: political polarization, homelessness, government spending and taxation, gun violence, health and fitness, and diversity/inclusion just to name a few.

And that means we have to dig deep. And before I say “we”, let me own what I need to do first before applying it more broadly. I have to hold myself to a high standard of integrity and results. And then when I do that, I have to hold my team, whatever that “team” is, to a high standard of integrity and results. And then, maybe just maybe, if the world needs me to step up and hold a community to a high standard of integrity and results, I’ll even have the credibility to try.

High standards matter. And we need as many people as possible to hold themselves and then others to a high standard, so that when the situation demands there are enough people with the credibility to even try moving our culture forward. And that starts with holding ourselves, myself included, to a high standard of integrity and results. Only then can we influence others.

Who is low-potential, exactly?

We have exclusive programs for people with “high-potential”. If we do that, then who exactly is “low-potential”?

There are lots of organizations that have programs for “high-potentials”, cohorts of “emerging leaders”, or who’s who lists for “rising stars”.

But lately, I’ve wondered: if we have programs for “high-potential” talent, who is “low-potential”, exactly? It’s audacious to me that we consider anyone low-potential.

With the right role, coach, opportunities, and expectations, my experience suggests that just about anyone can grow and thrive and make a tremendous contribution to whatever organization they are part of. Moreover, in my experience the most important ingredient needed for someone to be “high-potential” is that they want and are motivated to grow and be better.

It seems to me that a better approach than creating high-potential programs or leadership development cohorts that are exclusive is to design them in such a way that anyone who wants to opt-in and put in the work can participate.

And wouldn’t that be better anyway? Aren’t our customers, colleagues, shareholders, and culture all better off if everyone who wanted to had a structure where they could grow to their fullest potential? Even if not everyone ends up being a positional leader, don’t we want every single person in our companies to be better at the behavior of leading?

I don’t buy the excuse that it would take too many resources to design structures for developing potential that’s inclusive rather than exclusive. Software makes interaction much cheaper and scalable. People are really good at developing themselves and learning from their peers, given the right environment. And, in my experience most people are willing to coach and mentor someone coming up if that person is eager to learn and grow.

I definitely would want to be persuaded in a different direction,.however. Because to me, employing the best ways to prevent human talent from being wasted is worth doing, even if it’s not my idea that wins.

But again, if someone is truly motivated to grow and make a greater contribution, who of those folks are low-potential, exactly?

Status fights and wasted talent

What to do if your company feels like a high-school cafeteria.

Companies, and really any organization, can function like a fight for status. This “fight” plays out in organizations the same way whether it’s a corporation, a community group, or a typical school cafeteria.

There’s a limited number of spots at the top of the pecking order, and the people up there are trying to stay there, and those that aren’t are either trying to claw to the top or survive by disengaging and staying out of the fray.

If you’re engaged in a fight for status there are two ways to win, as far as I can tell: knocking other people down or promoting yourself up.

Knocking other people down is what bullies do. They call you names in public, they flex their strength, they form cartels for protection, and they basically do anything to show their dominance. They become stronger when they make others weaker.

This is, of course, easy to relate to if you’ve ever been to middle school or have seen movies like Mean Girls or The Breakfast Club. However, the same sort of dominating behavior that lowers others’ status occurs in work environments.

“Bullies” in the work environment do things like interrupt you in a meeting, talk louder or longer than you, take credit for your work, exclude you from impactful projects, tell stories about your work (inaccurately) when you’re not there, pump up the reputation of people in their clique, or impose low-status “grunt work” on others. All these things are behaviors which lower the status of others. In the work environment, bullies get stronger by making others weaker.

The other way to win a status fight is to promote yourself up and manage your perception in the organization. In the work environment, tactics to promote yourself up include things like: advertising your professional or educational credentials, talking about your accomplishments (over and over), flashing your title, hopping around to seek promotions and avoid messy projects, or name dropping to affiliate yourself with someone who has high status.

Let’s put aside the fact that status fights are crummy to engage in, cause harm, and probably encourage ethically questionable behavior. What really offends me about organizations that function as a status fight is that they waste talent.

In a status-fight organizations people with lower status are treated poorly. And when that happens they don’t contribute their best work - either because they disengage to avoid conflict or because their efforts are actively discouraged or blocked.

Think of any organization you’ve ever been part of that functions like a status fight. Imagine if everyone in that organization of “lower status” was able to contribute 5% or 10% more to the customer, the community, or the broader culture. That 5 to 10% bump is not unreasonable, I think - it’s easy to contribute more when you’re not suffocating. What a waste, right?

Of course, not all organizations function like a status fight and I’ve been lucky to have been part of a few in my lifetime. I think of those organizations as participating in a “status quest” rather than a “status fight”. In a status-questing organization, status actually creates a virtuous cycle rather than a pernicious one.

A status quest, in the way that I mean it, is an organization that’s in pursuit of a difficult, important, noble purpose. Something that’s aspirational and generous, but also exceptionally difficult.

In these status-questing organizations the standard for performance (what you accomplish) and conduct (how you act) is set extremely high, because everyone knows it’s impossible to accomplish the important, noble, quest unless everyone is bringing their best work everyday and doing it virtuously.

And when the bar is set that high, everyone feels the tension of needing to hit the standard, because it’s hard. Whether it’s to achieve the quest or be seen by their peers as making a generous contribution to the organization’s efforts, everyone wants to do their part and needs the help of others.

And as a result, the opposite dynamic of a status fight occurs. Instead of knocking other people down, people in a status-questing organization have no choice but to coach others up, which ultimately raises everyone’s status.

If you’re on a noble quest, there’s plenty of “status” to go around and the organization can’t afford to waste the contribution of anybody in the building - whether it’s the person answering the phone or a senior executive. In a status-questing organization, the rational decision is to raise the bar and coach instead of throw other people under the bus.

And what’s nice, is that in an organization with that raise-the-bar-and-coach-others-up dynamic is that the bullies don’t succeed, because their inability to raise and coach is made visible. And then they leave. And so the virtuous cycle intensifies.

So if you’re in an organization that feels more like a high-school cafeteria than an expeditionary force of a noble, virtuous quest, my advice to you is this: raise the bar of performance and conduct for the part of the organization you’re responsible for - even if it’s just yourself. And once you raise the bar, coach yourself and others up to it.

And when you do that, you’ll start to notice (and attract) the other people in the organization who are also interested in being on a noble quest, rather than a status fight. Find ways to team up with those people, and then keep raising the bar and coaching up to it. Raise and coach, raise and coach, over and over until the entire organization is on a status quest and any “bullies” that remain choose to leave.

Of course, this is one person’s advice. Looking back on it, it’s how I’ve operated (but I honestly didn’t realize this is how I rolled until writing this piece) and it’s served me well. Sure, I haven’t had a fast-track career with a string of promotions every two years or anything, but I have done work that I’m proud of, I’ve conducted myself in a way that I’m proud of, and I have a clear conscience, which has been a worthwhile trade-off for me.

—

Note: this perspective on equality / the immorality of wasted talent is well-trodden ground, philosophically speaking. John Stuart Mill (and presumably his contemporaries) wrote about it. Here’s an explainer on Mill’s The Subjection of Women from Farnam Street that I just saw today. It’s a nice foray into Mill’s work on this topic.

Clear, shared, expectations: in projects and parenting

My wife made a brilliant parenting move this week.

Our older son is 3, and we’re trying to work on table manners with him. At least 5 days a week we have been getting into some sort of tussle with him over playing with his food, chewing with his mouth open, or deliberately making a mess. Mealtime has been the most common trigger of friction between us all.

And the other day I asked Robyn what she wanted to do, and she calmly replied, “I have a plan.”

What she did was simple and immediately effective. When we were serving the next meal, she set expectations for our son as she was putting down his plate. “The expectation is that we eat Cheerios with a spoon, blueberries you can eat with your hands.” And on she went about sitting down properly and what can be dipped and what cannot.

Her plan of setting clear expectations, in advance, worked immediately. It was a master stroke.

—

My work colleagues and I have been experimenting with approaches to clarify expectations, too. Instead of doing a weekly check-in with a traditional project board, we made a “why-what-how” board.

Here’s a representation of what our board (which is just a slide in PowerPoint) looks like:

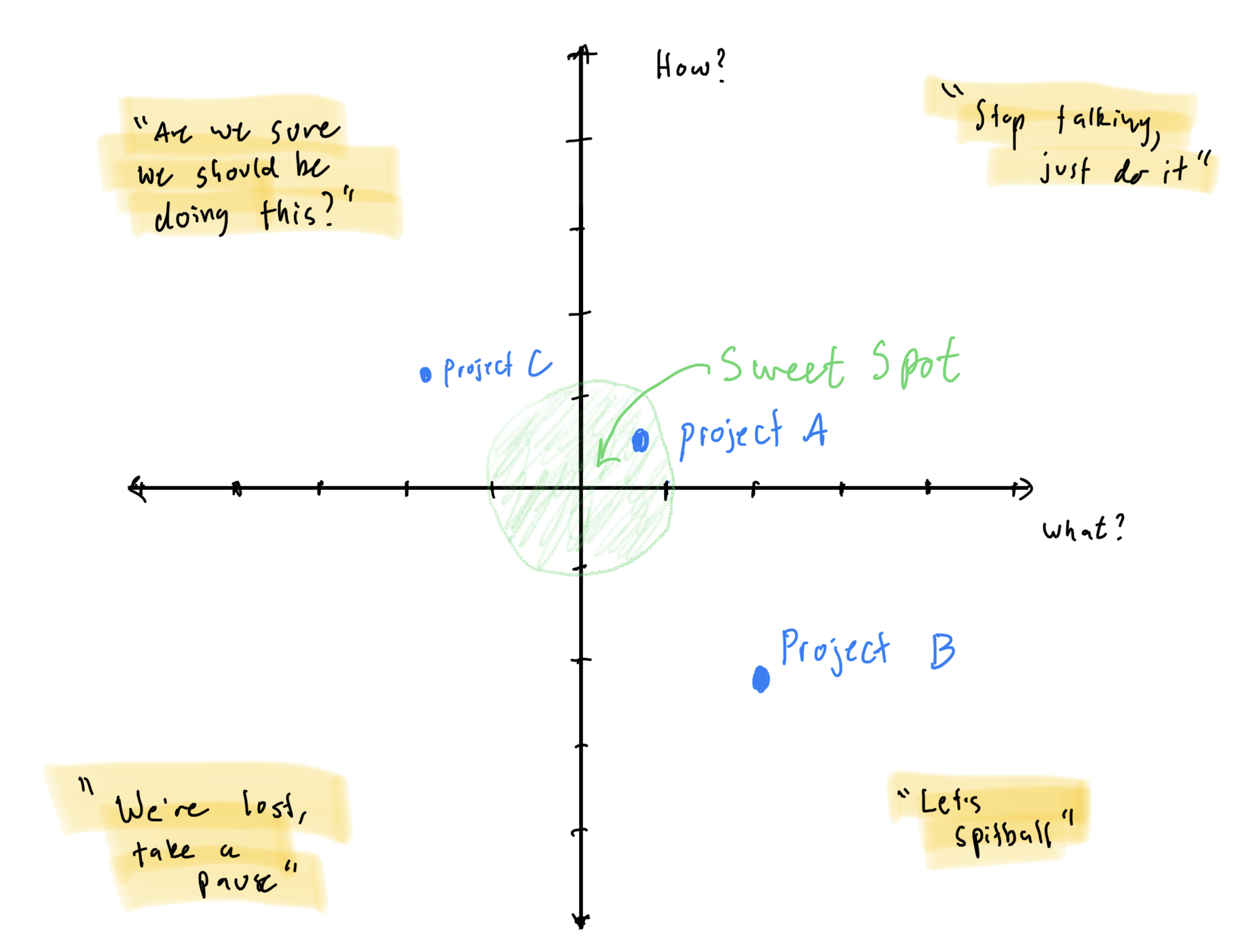

What we do each week is re-score and re-plot our projects on this chart together. The goal of this exercise is to ensure the project is in the sweet spot of clear, shared, expectations.

The x-axis is the what. We make sure we understand what the intended outcome of the project is. Do we understand the deliverables? Do we understand what success looks like and what result we are trying to create? If the value is left of the origin it means the what isn’t clear enough. If the value is to the right of the origin, it means we are over analyzing the intended outcome and/or talking about it more than we need to.

The y-axis is the how. We make sure we understand the steps we need to take to achieve the intended outcome of the project. Do we understand the major milestones and next steps? Do we have a plan for how we’ll actually get the deliverables and analyses done? Do we understand the roadblocks ahead? If the value is below the origin, it means the how isn’t clear enough. If the value is above the origin, it means we’re micromanaging the project or getting too prescriptive about how it should be done.

We ask ourselves each week, usually during our Monday morning check-in, where are we at for each project. If we’re outside of the sweet spot, we spend some time clarifying the what, the how, or both.

Each quadrant, conveniently, has a nicely fitting heuristic which gives us a nudge on how to get back to the sweet spot:

High how, high what: we are talking too much. Let’s just take action.

Low how, high what: we understand what we’re trying to accomplish, but need to talk about how we get there. Let’s spitball and figure it out.

Low how, low what: we’re totally lost. We need to take a pause, reset and understand everything clearly where we are. This is the quadrant where the project is at risk and we have to dig out immediately.

High how, low what: this is the we might be wasting our time quadrant. If we don’t know what we’re trying to accomplish, even if we nail the project tactically, are we even solving the correct problem? We need to clarify the what (usually by escalating to the sponsor) or end the project.

What’s not plotted on the graph, but in the data table that powers the graph, are a few other elements: the why and who and the immediate next step.

The why and who has been a recent addition to our board, that we added a few weeks after trying this out for the first time. This value is the motivation for the project. Why does it matter, who is it for, what positive impact is this project in service of, why should anyone care about it? We think about our who as one of four general parties, that are applicable, honestly, to any organization. Any project has to ultimately impact at least one of these stakeholders in a big way to have a compelling why:

Our customer

Our owners or shareholders

Our colleagues

Our society or the communities in which we operate

If we can’t think of a compelling reason why what we’re doing matters to at least one of these four stakeholders, why are we even working on this project? We push ourselves to understand why, for our own motivation and to ensure we’re not doing something that doesn’t actually matter.

We also ensure everyone knows what the immediate next step is. If that’s not clear we establish it right there so there’s no reason we can’t take action right after our meeting.

Our team only started experimenting with this since the beginning of the year, but I’ve been finding it to be much more helpful than a traditional project board where the conversation revolves around the ambiguous concept of “status” and “accountability”.

Instead of checking our “status” non-specifically, and being reactive to a project that is “off-track”, we ensure that everyone on the team has clear, shared, expectations on each project, and we chip away at getting into the sweet spot of clarity on a weekly basis. By using this approach, we end up teasing out problems before they become large. Because after all, how often do projects get off-track if the why, what, and how of the project are clear to everyone, all the time? Rarely.

This approach is also much less autocratic than a traditional project board. Instead of the “manager” being dictatorial and projecting authority, this process feels much more democratic and equal, relatively at least. We all are working through the why, what, and the how together and even though one of us on the team is the titular “manager”, it feels more like we’re all on equal footing.

This is a good thing because everyone is more able to speak up, ask questions freely, and bring their talents forward to benefit the team and the people we’re serving. It’s less of an exercise where everyone is afraid of not having hit their milestones and therefore trying to tap dance around the status of the project.

There is of course a time and place for “status” and “accountability”. Of course, deadlines and results matter and we have to hit those. But what I’ve found so far is that by having clear, shared, expectations we are in a perpetual state of forward motion. We hit our deadlines as a natural consequence of having clarity. As is often said, but no less true, an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.

As is usually the case, what my wife and I are learning as parents is incredibly relevant to what we are learning about management and leadership. In this case the lesson is simple: clear, shared, expectations lead to better results (and less strife).

The Weekly Coaching Conversation

Coaching others is definitely the most important and rewarding part of my job. When I took on this responsibility, I worried: would I waste my colleagues’ talent? How do I help them grow consistently and quickly?

Here’s a summary of what I‘ve been experimenting with.

Experiment 1: Dedicate 30 minutes to coaching every week

I raided my father-in-law’s collection of old business books and grabbed one called The Weekly Coaching Conversation: A Business Fable About Taking Your Game and Your Team to the Next Level.

The idea in it is simple: schedule a dedicated block of 30 minutes every week with each person you’re responsible for coaching. I thought it was worth trying. As it turns out, it was. Providing support, feedback, and advice falls by the wayside if it’s not part of the weekly calendar - at least for me.

Experiment 2: Ask Direct Questions

We start each 30 minute weekly meeting the same way, with a version of these two questions:

On a scale of 1-100 how much of your talent did we utilize vs. waste this week?

This question is useful because it’s direct feedback from the person I’m trying to coach. I can get a sense of what they need. Most of the time, what is holding them back is either me, or something I can support them with, such as: more clarity on the mission, an introduction to a subject-matter expert, some time to spitball ideas, or just some space to explore. This is also a helpful question to ask, because when the person I’m coaching is excited and thriving, I get to ask them why, and do more of it.

What’s one way you’re better than the person you were last week?

This question is useful because it helps make on-the-job learning more explicit and concrete. We get to unpack results and really see tangible progress. Additionally, I get a sense of what the person I’m coaching cares about getting better at which allows me to tailor how I coach them.

Experiment 3: Stop controlling the agenda

At the beginning, I would suggest an agenda for our weekly coaching sessions. But over the course of 3-5 weeks, I transitioned responsibility for setting the agenda to the person I’m coaching. This works out better because we end up focusing our time on what matters to them, rather than what I think matters to them (which is good, because I’m usually wrong about what matters to them).

It also works out well because my colleagues are in the driver’s seat for their own development. And that fosters intrinsic motivation for them, which is really important for fueling real growth. I certainly raise issues if I see them, but it frees up my headspace and my time to be responsive to what they ask of me.