When the pandemic ends, our generation has a choice to make

Every generation has to take it’s turn and lead. For millennials, our time is nearly here. How will our grandchildren remember us?

Our family had a nice run.

We made it through the peak of Omicron before the first member of our household tested positive for Covid-19, this weekend. Thankfully, we’re all fine so far. God willing, our nuclear family’s bout with Covid will pass in a few days and fall into the footnotes of our family’s history.

Ironically, the moment we saw the positive test, it felt like the beginning of the end of Covid-19, for our family at least. Assuming we get through this week without requiring hospitalization (which it seems like we will, fingers crossed), Robyn and I can breathe easier through the next few months as the pandemic hopefully transitions to an endemic. We’ll have gotten it and got through it. Our family is in the endgame. Thank goodness this didn’t all happen the week of Robyn’s due date.

Soon enough, the collective Covid endgame for our country and world will come, too. And when it does, I expect the narratives of what’s next to start forming. It’s what we do in contemporary human society: when crises end, we start to rewrite history.

It’s perhaps unnecessary to say something this obvious, but I don’t think the stories we’ll tell about the end of Covid will be along the lines of, “we just went back to the way things were.”

Our collective minds have changed; something inside us has snapped. We all went just went through an existentially-affective experience. Everyone has lost someone in some way. Some of our communities were ravaged. We all went through waves of lockdowns and uncertainty.

I don’t know about you, dear Reader, but I do not feel like the same person I was two years ago. Like, I feel like a very different person that I was two years ago - with different perspectives on family, work, gender equality, social policy, leadership, health, and public service.

And because we won’t just go back to the way things were, the question becomes - what will the story be? At the end of our collective reflection, what will the call to action be as we emerge from Covid-19? What narrative will be choose to accept and make real?

Speaking as a member of the millennial generation as I write these words in early 2022, the next 20-30 years are ours to lead. We’re at the age where our parents are retiring and we’re stepping in. And if the next 20-30 years are truly our turn to lead, what will our story be?

To contemplate questions with generational implications, I prefer to think in generational terms. The best judges of how we lead as a generation are not us, but our grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

So what I think about is what my children will say to their grandchildren about me. When Bo and Myles tell their grandchildren about how their father and his contemporaries acted between 2020 and 2050, what stories will they tell about us? As the true arbiters of our history, how will our grandchildren and great-grandchildren judge us?

I see two prevailing narratives, starting to form already. The one I think we all expect is the one typified by the big speech.

This is the story that begins with the President and other world leaders making a national address on television, ritualistically performing all the usual elements of pomp and circumstance: claiming victory, honoring the dead with semi-sincere words and and calculated phrases, and celebrating the front-line workers who carried the burden of the pandemic. In the final overtures of the speech that politician - whether Republican or Democrat - will play into our fears and darker memories of the pandemic, and vow: “Follow me, and I’ll make sure something like this never happens again.”

There will be a blue ribbon panel, scapegoats will be shamed and punished. There will be grand, short-sighted gestures implemented to help the nation feel like something will be different, whether or not they actually make things different. And then a few years will pass, the next crisis will emerge, and the same farce - muddle through crisis, posture and stoke fear, gloss over problems, and move on - will repeat.

I do not want that fear-based narrative to be how our grandchildren and great-grandchildren remember us.

The other prevailing narrative I see brewing already is that of enlightened self-awareness. It goes kind of like this.

First, there’s an awakening. Something shaken up in our heads because of the pandemic. We realize life is too short for jobs we hate and keeping up with the Joneses. We lean into our family life or our passions. We, as a generation, pursue our own dreams instead of everyone else’s. We become a generation, not of dreamers, but people who actually chased their dreams and poured everything into the relationships that meant the most to us. We become heroes because we stayed true to ourselves; the generation the finally broke the cycle and began the process of collective healing. The story is so intoxicating, and feels so familiar, doesn‘t it?

Lately though, I’ve worried about the slippery slope of that hero’s journey. If we all pursue our own dreams and build up our own tribes, where does that leave the community? Will we balkanize our culture even further? Will we put ourselves on a path of endless tribialization and greater disparity between those who have the surplus to “do their own thing” and those who don’t? Isn’t it so easy for this narrative to start as as a story of self-actualization but then end as a story of narcissism, self-indulgence, or elitism?

It seems innocuous if we individually pursue our own dreams and invest in relationships with our own loved ones. But what happens if we all narrow our focus to that of our own dreams, our own passions, our own families, and our own tribes? What will happen to the bonds that bind us? Is that a world we actually want to live in?

I sure as hell don’t want to be known as the generation who perpetuated a cycle of fear. But I don’t want to be the generation that turned so far inward that we lost the forest for the trees, either.

What I hope, is that our children and grandchildren remember the next 20-30 years as a time where our generation looked inward, and in addition to advancing own passions, families, and tribes, we also took responsibility for something bigger.

What if in the next three decades we came out of this with an awakening, yes, but an awakening of honestly embracing reality. Where we really understood what happened, all the way down to the roots. Where we asked ourselves tough questions and accepted hard truths about our priorities, our institutions, and our sensibilities about right and wrong.

And what if instead of pursuing quick fixes, we acted with more courage. What if we stopped putting band-aids on one big thing. Just one. Maybe it’s one issue like caregiver support or global access to vaccines. And we drew a line in the sand, and just said - this global vaccines thing is hard, but we’re going to figure this out. We’re not going to kick the can down the road any longer. We’re going to invest, and we’re going to do the right thing and do it in the right way.

And what if that one single act of courage, inspired another. And that inspired another. And another and another. What if instead of a cycle of fear, we ended up with a cycle of responsibility?

I know this is all annoyingly lofty and abstract, and probably a bit premature. But after every crisis comes a VE Day or a VJ Day or something like it. After every crisis comes a writing of history. After every globally significant event comes an inflection point, where the generation taking the handoff has to make a choice about what comes next.

For us as millennials, we’ve drawn the cards on this one. The end of the Covid-19 pandemic is right when it’s our time to take the handoff from our retiring parents, and step into the role of leading this world. It’s our time, our turn, and our burden.

When the Covid-19 endgame finally arrives, and our handoff moment is finally here, I don’t want to be swept up in it so badly that I can’t think clearly. I want to choose the narrative for the next 30 years with intention.

And the only way to do that I can see is to start thinking about the handoff we’re about to take, right now.

And I hope the narrative we choose is not fear, nor narcissism. I hope the story we choose and the story we commit to write, in each of our respective domains, is that of courageous responsibility.

I hope the James Webb Space Telescope changes human history

Exploring space has expanded what we believe about the universe and ourselves. The James Webb Space Telescope could change everything that follows.

As I write this in January of 2022, the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) is hurtling intrepidly to Lagrange Point 2, its home for the duration of its mission, about 1 million miles away from Earth. Launched on Christmas Day in 2021, the construction and launch of the observatory was a massive undertaking - spanning 25 years, at a cost of $10B, involving a team of 1000 people, and the space agencies of 14 countries.

When it arrives at LG2, it will calibrate its instruments, which are protected by a tennis court-sized sun shield that will keep its onboard instruments at a chilly -374 F temperature. Without this protection the warmth of the Earth and the Sun would interfere with the telescope’s ability to detect infrared wavelengths, such as the ones emitted just after the birth of the universe, which the JWST will study during its mission.

The mission’s four science goals, are as simple as they are profound:

The observatory’s planned mission is ten years, with its first images expected in June of 2022. Between now and 2032, I think we will learn many very important things about the universe. Perhaps even something that changes the arc of human history.

One of the deepest existential questions we ask as humans is, “are we alone in the universe?” In ten years, I doubt we will have a concrete answer to that question. But even if we had a shred of evidence, that gives us something - some clarity, a more accurate probability, something - wouldn’t that be absolutely incredible?

I am inspired and in awe of the possibility of what we could learn, rather than the reality of what we will learn. What if we learned that the proportion of habitable planets is significantly larger than what we currently estimate? What if we observe that the universe’s early formation makes it possible to predict where habitable planets will cluster? What if we learn that organic life is more possible than we thought?

If we realized that the development of other space-faring species is just a little tiny bit more possible than we currently think, it would open the door to ask dramatically new questions and contemplate exponentially more ambitious possibilities.

If we realized there were many more habitable planets, for example, wouldn’t we imagine if we could explore them? If we realized that space-faring aliens were more likely to exist than we thought, wouldn’t we try to imagine what they may be like, and how their societies may work? Wouldn’t we become more open to thinking about life’s biggest questions with more wonder and possibility?

And yet, despite all of the possibilities of what could be out there in the universe. I think the most profound conclusions we’d have if we look out into the universe will be introspective, helping us to examine life on Earth. By looking out into the expanse of the universe, the most important conclusions we’d draw could be about ourselves and about our own existence. The JWST will help us look outward, but also powerfully inward.

For example, I think often about what I call exomorality, which is trying to philosophize about the moral frameworks space-faring aliens might have. I wonder about how resource constraints on our planet, our physical bodies and lifespans, may affect how we contemplate right and wrong. Would aliens be different? Is it possible to have a society that doesn’t have rigorous ideas of right and wrong? Why? How?

I’ll concede that my forays into exomorality are a bit of a fool’s errand and just a tad premature (but it is fun). But even if I’m 100% wrong about the morality of aliens, it’s a liberating way to reflect on our own, human, morality. Looking outward makes it easier to look inward.

Despite my eagerness to hear about the possibility of habitable worlds and alien species, the JSWT may reveal the opposite. By looking outward, we may instead learn that the universe is an even more barren place than we thought. And learning that may be even more transformative for our species than if we discovered more signs of life.

What if we learn that the likeliest outcome is that we’re mostly alone out here? What if we learned that the conditions for organic life are incredibly and exquisitely rare?

Imagine how quickly how we view ourselves might change if we realized, simultaneously as a species, that maybe we don’t have a safety net. That there is no techno-civilization out there to learn from; no deus ex machina. Maybe there’s really nowhere else for us to go, even if we could get there somehow. Maybe we are alone out here and this one precious Earth really is all we have.

I’m certainly not a NASA scientist, and these hypotheses are all my own. And I doubt we’ll have any absolute “proof” to validate any of the thought experiments I’ve suggested here, especially after just 10 years.

But what if we end up having 1% more clarity on something related to these deepest of the deep questions? What if we have even 0.5% less doubt about some question related to life in the universe?

If we have some evidence, of some thing, that gives us a foothold to think deeper and explore further - I think that could change everything that follows.

I love space. I have followed NASA since I visited the Kennedy Space Center as a kid and somehow got a scholarship to go to space camp. I read interstellar travel blogs, still. I think about aliens, like, 5 times a week at least (just ask my wife, ha!). Perhaps most controversially, I like both Star Wars and Star Trek, (gasp) equally. Especially for a non-scientist, I’m a space nerd of galactic proportions.

Thinking about space is what nurtured my ability to dream and dream big. Like it does for millions across the planet, space exploration gave me something, from an early age, to grab onto, that made it possible to believe in something huge and that anything may really be possible.

Just looking up, on a clear night, is as much a path to a spiritual plane to me as going to church, performing a pooja, or doing transcendental meditation. Seeing a sky full of stars from the trails of our nation’s national parks is still among the most beautiful, humbling moments I’ve ever been part of.

Our efforts to explore our solar system and our universe have already given us, as a species, so many images that have expanded what we, as a species, believe is possible. Exploring space, and going out there, into the final frontier has helped so many people across our entire planet imagine the magical and magnificent possibilities of this universe.

Images like Earthrise from Apollo 8, which some credit as starting the modern environmental movement:

Or this “small step” moment from Apollo 11:

Or this image of our “Pale Blue Dot” from Voyager 1 which Carl Sagan famously reflected on:

For me and so many others, what we’ve seen and learned about by exploring space has expanded what we believe is possible. And it’s expanded what we believe we can be.

I’m not at NASA scientist, clearly. So do I actually know what we might learn during the JWST’s mission? No, not really. I’ll concede that too.

But let’s remember, we’ve just launched the most powerful telescope with the most ambitious mission in the history of human kind. For goodness sakes, we will be studying the birth of the universe a few hundred million years after the Big Bang, a few blinks of an eye in universal terms. With such bold ambitions, even if what we discover during the JWST’s mission is just 1% of what I hope it is, it could fundamentally transform how we perceive the universe and ourselves.

In 2032, we will probably still have income inequality or political strife. We will probably still have a warming planet. We may still have many of the problems which plague us today (fingers crossed, NOT Covid). But I think it’s possible that in 10 years, when the planned mission of the James Webb Space Telescope comes to a close, we may have learned something that dramatically expands what our species believes is possible. And if we learned something like that, it could change everything that follows.

Other Links:

https://jwst.nasa.gov/content/about/faqs/faq.html

https://jwst.nasa.gov/content/science/index.html

https://jwst.nasa.gov/index.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Webb_Space_Telescope

I Believe in Christmas Magic

Our Christmas Tree is our life story, our histories intertwined with the branches and lights. It is the only time machine I know of that actually works - drawing me into memories and stories of a different time and place. This to me, is magic.

There is magic in Christmas, and I believe in it.

The root of where my belief comes from is our family’s lore, originating from a time just preceding my birth. As the story goes, my parents were having a hard time conceiving. At the time they were new immigrants to this country, living in Chicago, I think.

They didn’t have much support or know many people. I can only assume they had little money. As I recall, my father insisted upon my mother learning English. And so she went, taking the bus in the dead of winter, to a Catholic Church that offered English classes to new Americans.

And if you know Chicago, it’s damn cold in the winter. And yet, despite my mother’s protest, my father sent her off trudging through the frigid city to learn to speak the language of this country.

At some time during that season of their life, my mother prayed. Prayed in the broadest sense, I suppose, but really she was making a deal. She promised, to whom I don’t know, that if she was blessed with a child she would put up a Christmas tree, every year.

I am obviously here now, and sure enough, every year a Christmas tree goes up in our Hindu household, for reasons bigger than the commercial and assimilating to avoid conflict. On the contrary, we have not assimilated into Christmas, we have assimilated Christmas into us.

Christmas trees are a durable tradition for Robyn and her immediate family, too. Every year on Thanksgiving she trims the family tree while her mother cooks dinner and the rest of the crew heads to the stadium to watch the Detroit Lions football team, almost invariably, lose the Thanksgiving Day game.

In our own home, we have created our traditions with each other and our children. We trim the tree right around Thanksgiving and start a solid month of listening to Christmas music and watching Christmas movies, always starting first with White Christmas. We eagerly await the first weekend snow, and like clockwork we watch The Polar Express and drink hot cocoa. We unpack and read classic books out of the seasonal box, like How the Grinch Stole Christmas, or ‘Twas the Night Before Christmas which Robyn’s father reads to the family on Christmas Eve, after we all go to church, eat a family dinner, and do a secret sibling gift exchange.

But of all these traditions, and others I haven’t described in detail, the Christmas tree is still the most mystic and alluring. It’s where the magic of Christmas has always resided, at least for me.

After we put up all our ornaments and trimmings and lights, I find myself, every year, sitting on the wooden floor of our family room, carefully studying the tree. This year, I had our sons beside me, for a fleeting moment at least, looking up. It is our family yearbook up there.

Every ornament has a story, a purpose. There are ornaments from Robyn and my’s childhood, representing our experiences and interests growing up. Then there are the ones that represent significant moments in our life together - like our first Christmas together, our first home, or the metallic gold guitar ornament we bought in Nashville which commemorates our honeymoon.

There are ornaments demarcating when our family has grown, dated with the births of each of our children. There are the ornaments we have from our family trips, most recently a wooden one we luckily found in the gift shop on our way out of North Cascades National Park.

Our Christmas Tree is our life story, our histories intertwined with the branches and lights. It is the only time machine I know of that actually works - drawing me into memories and stories of a different time and place. More than that, it’s a window to the future, leaving me feeling wonder and hope for the possibilities of the coming year. When I am there, at the foot of the tree, sitting at the edge of the red tree skirt, I am all across the universe.

This to me, is magic.

As I am sitting here writing this, it is the Sunday after Thanksgiving in 2021. The first weekend snow fell last night. We are in our family room, watching The Polar Express. Robyn and the kids brewed some hot chocolate, right on cue with the appropriate scene in the film. I see them all on the couch, snuggling a few feet over from me. Our family Christmas tree is immediately behind me, the reflection of it’s lights glowing softly on my iPad screen.

I see the snow covered branches, wet and heavy, out our study room window. The neighborhood is quiet and our radiators are toasty warm, as if we were able to set them at “cozy” instead of a specific temperature.

As I sit here, trying my hardest to soak up this moment, I know that much of the stories we share at Christmas, like Santa Clause’s sleigh and reindeer, Frosty the Snowman, and any assortment of Christmas “miracles” reported on the local news probably are not true, strictly speaking. I cannot verify them or explain them enough with empirical facts to know they are true. And I will never be able to.

But I still believe in the magic. Because of the tree, and what happens nearby.

Our tree, and what it represents, is a special relic in our family. As we put it up, year after year, it reminds me that our history is worth remembering and that our future is something to be hopeful about. Our tree, and what it represents, renews my belief that there is magic in Christmas.

The fear of wasting our talent; living a happy but unremarkable life

The funny thing is, I still feel this dread, even though every day I have bubbles, and even overflows, with joy.

This, decidedly, the life I chose and I wanted. “Family first” is our mantra and “It’s a good life, babe” is our refrain. We have a fairly simple life that’s fun, and fulfilling. And joyous. And meaningful. Our days, admittedly, are remarkable mostly because of their consistency.

Our kids waddle into our room, wearing their pajamas of course, at about 6 AM on most days. Robyn and I work our jobs. If it’s a school day, we go through our morning routine with the kids and “do drop off” as a family. If it’s a “home day” we all move a little slower as I prep for the work day and Robyn prepares herself for a day with the kids - mixing in walks with Riley, swim lessons, doctors appointments, snacks, and other modest mischief and adventure throughout the day.

What anchors our day, on most days, is a free-flowing sequence of cooking dinner while the kids play, followed by a family dinner, dessert, tooth-brushing, potty, pajamas, two stories, and a lullaby before tucking them in.

Our nights and weekends waltz and sashay with different versions of roughly the same activities. We do whatever remainder of work we haven’t crunched through during the day, which luckily isn’t as pervasive, urgent, or stinging as when we both worked in public service. We have chores that never seem quite finished - dishes for me, laundry for Robyn. In the rare instance we watch television, it’s either a British detective drama like Endeavour, or a music competition like The Voice or The Masked Singer.

If it’s a weekend, our chores remain but are different (groceries don’t buy themselves, yet, at least). Our excursions outside are a little longer and a little more like a sauntering ramble than the focused, brisk walk Robyn and I take with Riley at lunchtime when we’re both working from home.

And then there are the weekend’s mix-ins. We take Bo to soccer practice and try to go to church and participate in civic and cultural life as best we can. We do our best to see our family once a weekend and nurture friendships with our small group of close ties, our neighbors, or extended family. We both steal away an hour of exercise, as many times we can.

I try to write and chip in to the efforts of the neighborhood association and Robyn tries to explore her budding interest in photography, plans trips, and tries to support the other young moms she knows through small but deliberate acts of kindness.

The moment of the week I relish most, probably, is a short window between 8 and 10pm Friday nights. That’s the one part of the week where Robyn and I are most likely to be able to spend together, doing nothing but enjoy each other’s company. This, again, is remarkable only because of the consistency of our activity - we watch a show perhaps, open up a bottle of wine, fire up the power recline feature of our La-Z-Boy love seat, and or listen to some light music while absorbing and reflecting on the last week of our life. It is the time of week, I feel most comfortable.

This is our life. And as I said, it would otherwise be unremarkable if not for its consistency. Because it truly is unglamous, and seriously is not for everyone. Plenty of people would probably go bonkers under our roof, as we would under theirs.

But for us it works. Because as consistently unremarkable our daily grind is, the moments of laughter, joy, love, and gleefully, willing suffering & sacrifice - the moments we live for - are consistent and remarkable.

It’s hard to explain, but there’s an inexplicable ease and warmth I feel when our sons cast spells of “giant golf ball powers!” completely unannounced. Or when we have 60 minutes of struggle and yelling and tears to get out the door, only to spend an hour and a half with someone at their birthday party. Or when we get to walk outside and see the majestic 100-year old trees triumphantly changing color down our block. And there are dozens more small moments like this, which are unremarkable in isolation, but their consistency feels remarkable.

This is the life dreamed of when I was wandering through the badlands as a younger man. It’s the life Robyn and I wanted together and that we both still want, even though we have to hustle for it damn near every day. It is a happy life, made more exquisite by how challenging and sacrificing it is.

This is the life we chose, intended with each other. It is a life on purpose. Every day is a good day, truly. Our life is admittedly quite opposite of a novel, flashy life - much closer to boring than glamorous, more like monochrome than technicolor. But it’s still a thrilling adventure - healthy, prosperous, joyful, and meaningful,

And yet, I hear the echoes of my father’s stubbornly accented voice and the dream-like memory of him talking to me in the kitchen of my family home - “you are a very capable person,” he said, in a way that was straining, almost exasperated even, to make me understand how serious he was.

And then, on top of my serene and happy state of mind, the existential dread sets in.

I have been brainwashing myself to stop comparing myself to others for the better part of a decade. And I’m mostly there, I don’t feel jealously of my peers like I used to. I don’t have the addiction to keep up with the Joneses or stack up my professional resume like I used to. Instead of being acute, my inclination to social comparison and seeking the approval of others is now more of a chronic condition - something I can manage and live with, rather than having to treat intensely after a bad episode. I am more comfortable doing my own thing than I ever have, and I have a better grasp of what “doing my own thing” or “being myself” actually means, than I ever have in my whole life.

This relatively nascent state of contentment has come from looking inward. It has come from consistent, intense, reflection trying to understand my inner world and how that inner-self can integrate with the broader world. I suppose you could say, I’ve tried to put into practice an “examined life” as Socrates put it in Plato’s Apology.

But in that act of examination, I haven’t been able to help but contemplate whether I’ve lived up to my Father’s assessment of my talent, or even my own assessment of my own capabilities.

Because it’s true, I am a capable person, even if I was afraid to accept the responsibility that came with acknowledging those capabilities for most of my life. And so I wonder, have I lived up to what I’m capable of? How much of my talent and time have I squandered?

To be clear, I’m under no delusion (anymore) that given different choices, I’d be more wealthy of famous than I am now. The way I operate and think, I’ve accepted, it not attractive of fat profits or paparazzi. And, I know for sure that I’m not a once in a generation genius whose wasted talent has become a missed opportunity to bend the trajectory of humanity.

What I long for and am haunted by, however, is contribution. Meaning, lower-case “c” contribution. Like how many more people’s days could I have made by now, had I made different or better choices? And by different choices, I don’t even mean sacrificing family or my own sanity to work harder or longer hours. But maybe if I had focused differently, or made different choices on the margins, or gotten drunk on fewer weekends in my twenties, or just tapped into my talents more intentionally or earlier..

How much higher would the literacy rate be if I applied myself to it? How many fewer people in Detroit would have been shot or killed had I stayed in public service for longer or been better at my job? How many companies could I have started by now if I acted on one of the dozens of businesses that I’d thought of with my buddies that ended up becoming profitable enterprises? How many people could I have brought out of a dark place had I lived up to how capable I actually am and been more generous? What might’ve happened if I buckled down and finished this book two years ago? How might the world be a little different, and hopefully better, if I were better and contributing my gifts?

Perhaps the dread I feel is better described as remorse. I have everything I dreamed of, and it truly is enough - I feel fully happy, complete and satisfied. And yet, I feel this guilt and a lingering malaise because I know I had more in the tank to give. I know that in a different version of my life, somewhere else in the multiverse, I would’ve been able to create a cherished and charmed home life while making a greater contribution to the world outside our backyard.

And I suppose it’s true that life is long, and many people don’t hit their stride until well past middle age, some even not until their sixties or seventies. It’s just this bizarre reality where I feel confident in the choices that I made, feel blessed and complete in the life I have, but still feel the heaviness of imagining counter-factual life.

I wonder often if this must be a new phenomenon for people coming of age. Because now, for people coming of age right now, we have a much broader understanding of the world and our role in it. The amount of information we have or travel we can do or people we can interact with, gives us a difficult awareness both of who we are and how we influence others. This heaviness of imagining a counter-factual life probably wasn’t possible for nearly as many people even 30 years ago.

What I’ve tried to take relief is is that despite how informed or worldly we can be in today’s time, we still know very little of how far our actions actually travel. We don’t know the extent of the wake we’ve created for others to be cared for, to grow, to live more freely, or to thrive. Because now, the contribution and goodwill of our actions can travel much farther than they could 30 years ago. This is true because of how globalized our world is, even if most of us aren’t destined to have a litany of press clips to our name because of what we do on this earth.

What I hope for now is that even though most of the contributions that most of us are able to make are unremarkable, we just keep doing them. Over and over. If we consistently put good things out into the world, maybe just maybe it will turn to be remarkable and make an extraordinary contribution. With any luck, if we’re at least consistent in being unremarkable we’ll be towards the end of our lives and we’ll see that our talents weren’t squandered and we’d been making a remarkable contribution all along.

The bar is too low for men as parents. Enough is enough.

I want to get out of this self-perpetuating cycle of men being held to a low standard of parenting.

After four years of being a father, I’ve noticed several ways that other people treat me differently as a parent than Robyn. Here are some examples:

In the past three months, Robyn and I each took 2-3 day trips away from home. When I left Robyn alone with the kids, it wasn’t much more than a blip on the radar. Nobody we knew stressed too much about it or honestly thought much of it.

When Robyn left me alone to solo parent for a few days, so many people offered to help in one way or another. It was a topic of some note, rather than just a passing mention. People, kindly, asked if I was scared to be home with the kids “all by myself. That was all very generous, but noticeably different than how Robyn was treated.

Robyn and I are also complimented differently as parents. Which is to say I actually receive compliments and Robyn, again, doesn’t get more than a passing mention. Robyn is an outstanding parent to our sons. I’m no slouch either, and we both love being parents so we share the load. Somehow, that leads me to get noted as an “involved dad” or “doing a great job” and Robyn gets that sort of affirmation much less, if at all.

Which, is all very kind. But it makes me feel like the often discussed example of a person of color being complimented as “articulate.” I usually feel like our culture must expect me to be some degree of uninvolved and incompetent to pay me a compliment just for being a father who isn’t a total moron.

At the same time, whether it’s school, the doctor, or even waiters at restaurants - if any person engaging in an arms length transaction needs any information about the kids’ wants and needs they almost invariably ask Robyn. Like, almost literally never am I asked about them, sometimes even by close friends and family.

It’s like the same dynamic of waiters automatically giving the man at the table the check at the end of the meal. I often feel like people assume that I’m off the hook for having any information or an opinion about our childrens’ affairs.

Finally, when in establishments that aren’t run by large corporates (like Disney World or McDonalds), it always seem like that the women’s bathroom is more likely to have a changing table than the men’s. To be sure, I don’t have hard data to back up this perception. But it’s happened enough times where the women’s restroom has a table and the men’s doesn’t that we believe it.

Net-net, in four years as a father, my experience strongly suggests that Robyn and I have different expectations as parents and are held to different standards.

To be real blunt: as a father, I have a chip on my shoulder.

Because from my vantage point, our culture is sending signals, 24/7, implying that men are beer-drinking, butt-scratching, sports-watching oafs that don’t have a clue on how to be caregivers to their own children. I feel like I’m constantly having to prove that I can be held to a higher standard than the abysmally low bar our culture sets for men as parents.

This is definitely a hyperbolic, stereotype-rooted, perhaps even ridiculous claim to make. But I feel it. Like all the damn time. It makes me bonkers that the bar is set so low.

I am not trying to get a pat on the back, or suggest that I’m some all-star father. Because honestly, I don’t deserve one. I decidedly am not.

I screw up with my kids and/or need Robyn to help me clean up a mistake I’ve made, literally daily. By all accounts, I’m a solid (but average) father, at best, with a solid performance thrown in about once every ten days.

What I am trying to do is bring light to the fact that our culture has self-perpetuating, low expectations around men as fathers. We treat men as if they’re incompetent fathers, make fun of them when they screw up, and then lower the expectations we have. And then, we give them less responsibility, which all but assures that those men will become even less competent and confident than they already are.

This cycle is infuriating to me because a lot of men I know (myself and many friends from all parts of my life) are trying really hard to be present, competent parents. I hope that by bringing light to this cultural phenomenon it will cause at least a few people to act differently. Because I don’t think most people mean to belittle men or imply low expectations for them - it just happens because it’s the culture.

That said, I get that there’s probably an equal number of men who aren’t trying to be competent parents. But conservatively, even if only 20% of men are actually trying, we shouldn’t be setting the standard based on the 80% who aren’t. No more low expectations. The bar is too low.

And for all you fellas out there, who know exactly what I’m talking about because you’re frustrated by the same pressures I am, let’s keep on plugging away.

Maybe you disagree, but I don’t think we want or need to be celebrated as “super dads” by our friends or family, just for being a competent parent. I don’t think we need to start a social movement or get matching t-shirts with some sarcastic tag line about how we’ve been stereotyped. I don’t think we need institutional relief or recognition. I’m probably being petty even just ranting about this.

Let’s just keep doing what we’re doing, until the bar of expectations rises and this beer-drinking, butt-scratching, sports-watching oaf that’s clueless persona is a thing of the past.

The dance of seeing and being seen

The world of children, I’ve found, can be a remarkable window into the world of adults. So much of our behavior, motivations, fears, and hopes end up being so similar, at their core, to those of children.

Little kids want to be seen, because they know intuitively that to be seen is to be loved. And adults, it seems, are not that different.

“Papa, watch this.”

I hear this often from Bo, our older son, and I turn my head to, well, watch. And then he will jump off a stool, flash his favorite dance move where we wiggles his knees, spin and wave a toy around, or do one of the many other things little boys do.

Little kids just want to be seen. Because in their world, it seems, seen means loved.

Perhaps our adult world is not that different.

I remember scanning bars in my early twenties, hoping not to miss my future wife, whoever she was, in case she happened to be there that night. I wanted her to see me. Or those times at work when I chimed in during a meeting with people who outranked me, to share an idea. I wanted them to see that I had something to contribute and that I was competent. Or even this blog, which I’ve been writing consistently for over 15 years now, to some degree I hope others see that I have something to say, and that it contributes something positive to their lives.

To be seen is to be loved.

And other times, we don’t want to be seen but want others to be seen. Like when we hold a memorial service for our loved ones who went ahead. When we put photos together on a memory board or a slide show, we want them to be seen and remembered. Or when we make sure everyone in the group shows up at a birthday party. We want them to feel seen. Or when a junior member of our team at work had a great insight, and we go out of our way to nudge them to speak up. We want their talent to be seen.

Wanting someone to be seen, is wanting them to be loved.

And perhaps the most generous act of the bunch is when we ourselves see others, in full frame and depth. Like when we go to our kids’ or grandkids’ or nephews’ soccer practices and school plays, we go just to see them. Or when we all inevitably have friends in town at the last minute, we change our plan so we can see them.

One of our dearest friends famously asks questions of the heart with incomparable sincerity, but also with piercing directness. Yesterday, when hanging out in her family’s backyard and chatting about her gift for deep conversation, she said with earnestness and unwitting grace, “it helps them feel seen.”

And tomorrow, Robyn and I have an ultrasound appointment, where we will find out whether our third child is a boy or a girl. I don’t truly have to be there, but I want to - it’s been blocked off on my calendar for weeks. And, there’s a reason why there’s always a big monitor in ultrasound examination rooms - parents get to see their children for the first time. Even if it’s through the blurry medium of an ultrasound photo, we get to see them. We move heaven and earth to see them.

To see someone is to love them.

So much of how we act in our day-to-day lives as humans seems to be shaped by our desire to see and be seen. It plays out in family life, social life, work life, and public life. Nobody but perhaps the most enlightened and secure among us seem to be above the fray. It does not matter if one is royalty or a commoner, wealthy or poor, famous or not, political leader or everyday citizen, theist or atheist - every walk of life engages in this dance: to see and be seen, to love and to be loved.

Why? Perhaps because to be invisible - unseen and unloved - can feel like a fate as grim as death. What is a life if one questions whether he is seen and therefore loved? And to be unloved is to be in danger, because we all know how the unloved are treated in our culture, and perhaps worse, how they are ignored.

And so it makes sense to me the lengths we go to be seen, even if it’s through mischief, foolishness, or outrage. The fear of being unseen makes people do crazy things. I know this because it has made me do crazy things: everything from doing a totally unnecessary amount of bicep curls at the gym to hootin’ and hollerin’ at the bar with my buddies to deriding myself into depression for not having a career trajectory comparable to my peers.

It seems like so much of the social struggles us center-left, center-right millennials often aspire to rehabilitate can start so simply, through this dance seeing and being seen.

Dreaming new dreams

At some point in the past 10 years, I stopped dreaming. Everything became goals and ROI and avoiding waste. I didn’t realize it at the time, and even in retrospect it was hard to see.

I don’t want that. I want to dream again.

But I’ve lost, for good reason, the youthful swagger and ignorance that propelled me to dream. The new question has become, how do we dream from a posture of humility?

My inner-critic-turned-coach finally, thank God, got my attention. He’s been probing me about dreams. And I finally stopped to hear him out, and he asked:

Neil, why the hell did you stop dreaming? When did it happen?

A piercing question. Before I could even answer, I started by defensively - and with futility if I’m being honest - rejecting the premise of his question. Of course I haven’t stopped dreaming. “Because I’ve got goals, dude”, I told him.

I may not be proud some of them, especially the ones about career and money, sure. Some of those goals, after all, appeal to the lesser angels of my nature I admit. But if I have goals, I means I haven’t stopped dreaming.

Right?

Okay, Neil, then tell me. What is a goal? What is a dream? Are they the same, are the different?

Goals, at their best, are specific and measurable. You either did them or you didn’t. They are linear and rational. Goals aren’t loosey-goosey, or they shouldn’t be at least. Some are ambitious, others are more attainable. Goals are SMART.

Perhaps goals are boring and drab, but by design. They are targets, and targets are meant to be hit with discipline and banshee-like intensity.

Goals are nouns which makes them tangible and real, even if they are a bit of an abstraction. They are part of our meta-life - the life we live in our heads thinking about and planning our actual lives - but that doesn’t make them any less concrete. Goals are real and strong. They are not fluff.

Dreams, it seems are different. And to call them dreams is to miss the point. The concept should be thought of as a verb: to dream or be in a state of dreaming. “Dreams” is almost a colloquialism like “the feels” that just describes where the paint lands on the blank canvas when we dream. “Dreams” are the souvenirs we get from time spent dreaming.

And when we dream, we’re almost deliberately not defining a concrete output that we want to achieve. It’s like the act of dreaming is a portal to a different world, where we imagine the world as we hope it to be. We are not the agent of the dream, we are merely observers and travelers in the dream-world around us. Dreaming is the creation of hope for a state of being or a feeling.

There’s something pure about dreaming. Unlike a goal, dreaming is not something we hope we accomplish, dreaming is traveling to a moment we hope will exist, for us as part of the larger world.

There’s a certain detachment of self that comes with dreaming, assuming one is not an egomaniac, incapable of imagining a world that goes beyond themselves. Dreaming, by its nature, feels like something that yearns to be bigger than ourselves and the bounds of what’s possible now.

It bothers me that sayings like, “a goal is a dream with a deadline” are things that are, well, sayings. It sullies the idea of what it is to dream. The magic of dreaming is that it need not be bounded by the ego, time, space, rationality, or the validation of being accomplished. Dreaming, I feel, is something that exists on a deeper spiritual plane than “goal setting.” Goals and the act of dreaming are different; we need them to be.

And, my inner-critic-turned-coach was right, I could not reject the premise of his question.

At some point in my twenties or early thirties, I did stop dreaming. Everything became a goal, something I could hold. Something that helped me to maximize the return on the investment of my time and energy and money and talent. I couldn’t just waste my precious life, I have to make sure I have something to show for it at the end.

It’s like my life became infected with the similar afflictions - the dreary desert sand of dead habit, or, narrow domestic walls - that Tagore contemplates in Where The Mind Is Without Fear. And now everything has to have a purpose, and is all about bangs for bucks and juices worth the squeezes and fitting in the plan and checking off Outlook tasks to hit deliverable deadlines and whatnot.

Good God, what the hell happened to me?

Neil, why did it happen?

What’s interesting is, even though most of my dreams are achieved now - Robyn and I have each other, a home, and children which covers the big ones - not all of them are.

I have longstanding dreams of Robyn and I as an old, bespectacled couple and going for slow strolls together, hand in wrinkly hand. I have dreams of our City and neighborhood being a clean, happy, and verdant place, where youngsters can’t believe that we ever had the levels of violence and poverty we have now. I have dreamed of a future where I the government is effective, fair, and compassionate.

I even have dreams of being an, old, dying man and spending time with my sons, while bedridden - not anything morose, just a natural consequence of a long life full of love; something I pray for because I never was able to say goodbye at my own father’s bedside.

I dreamed dreams, yes. But they are old dreams now. I haven’t dreamed new dreams. And any dreaming that I’ve done is measured and tempered - nothing I’d consider bold and daring, all the dreaming I’ve done lately is nearly within grasp. It’s about my own family, or close friends, or my street, which is great no doubt.

But some of the luster and zeal of my youth has obviously faded. I have not been dreaming of the stars or the broader world outside of my own backyard, quite literally.

There’s a certain arrogance that one must have to dream, perhaps. It takes so much time and stillness to dream. And that time could be spent working, or doing chores, or processing email. That required largesse to dream takes arrogance, or at least ignorance, to expend on something as fleeting as dreaming.

When we dream, we have implicitly acknowledge that we’re not doing something “productive” and assert that we are bold and important enough to have that time and mental energy to spend dreaming. Dreaming is not a practical act, it’s an action undertaken with audacity.

The irony here is that I’m in the most stable, comfortable, and experienced stage of my life so far. I have a steady job, a family that loves me, a roof, no want of food or health. I have made mistakes and learned from them. This is probably the best time to dream arrogantly, because I’m lucky enough to have far more - in terms of material resources and love - than my sanity requires.

Why did I trade all my dreaming and settle for goals instead?

Am I afraid because I’ve lived through some truly terrible days of grief and sadness? Am I just loss-averse and hesitant to “risk” the life I have by daring to dream of something beyond the four walls of our happy home?

Do I just think I need to be grateful for what we have and not insult the God and the universe by dreaming for something more? Am I afraid of disappointment or of running out of time? Am I just tired after long days of work, raising children, and the daily grind of washing dishes, mowing the lawn, and taking out the trash?

In my twenties, I correctly recognized that arrogance was probably my greatest character flaw. But by trying to purge myself of arrogance, maybe I also purged some of the helpful swag that creates the permission for a man to keep dreaming.

But if we have grown out of our youthful arrogance, we can still dream. We must still be able to dream. We need dream, even if it’s with humility instead of arrogance. It’s a dangerous thing when someone stops dreaming.

Maybe just like the afflictions, the answer of how to dream humbly also rests with Tagore in Where The Mind Is Without Fear where he invokes the mind being led forward - in his case to God - into ever-widening thought and action.

Ever-widening seems to be the challenge and the key. Dreaming humbly is dreaming with an ever-widening heart. It is dreaming with ever-widening love, expanding first beyond ourselves, and then expanding beyond our own backyard. And then expanding beyond our own time and space.

That widened heart, fills with love for what’s beyond just us, leaving no room for fear. When our ever-widening hearts become occupied with love, we have no choice but to dream. Love creates an involuntary reflex to dream again. We feel we must dream for what we love, the fear we have - and that pesky need to be goal-oriented and practical - can’t overcome that yearning to dream. For this greater good that we have come to love, a goal is simply insufficient.

We can push against the pressure and practicality of goals by opening our hearts to ever-widening love: compassion, honesty, and embrace of others. Foe those of us that have lost claim to our youthful arrogance and ignorance, the grace of loving beyond ourselves and our closely-knit ties is the inspiration and invitation we need to dream from a posture of humility.

There is hope for us yet.

Something more compelling than fear

I don’t want to live in a fear-driven culture for the next twenty years. I’ve grown tired of it.

It seems to me that “know thy self” is good advice to end an attachment to fear. If we have something more compelling to focus on, we have something to think about that’s more compelling than the fear others are trying to project into our lives.

Twenty years is the time a newborn child needs to come of age. For children born on September 11, 2001 that day would have been yesterday. Those children have come of age.

I remember feeling a placeless and faceless fear, frequently, over the past twenty years. Fear of terrorism, the competition of globalization, or the fear of death. Or the fear of missing out. Or the fear of racial tension, polarization, and social shame. The fear of being canceled or having to stand alone.

It seems to me, that fear was a recurring motif of the past two decades. These children have come of age in a time typified by its focus on external threats, assertion, and outrage. It gives me a weeping, grieving, sadness to think that they, those children, and we those others, have lived under twenty years of siege by a culture enmeshed with fear.

I do not want the next two decades to be a response to fear.

But how?

—

Apparently, there is a YouTube channel where classical musicians listen to K-Pop and comment on its musicality. An analytically-inclined colleague of mine told me about it when we were chit-chatting before a virtual meeting - about how she loves ballet and played the viola growing up. This YouTube channel uncannily blends three of her passions: classical music, analysis, and K-Pop.

It was one of those moments where everything feels light and elevated because you’re in the presence of someone who feels comfortable in their own skin. It was liberating to just listen to her talk about those interests of hers, because she was being her full self.

Know thy self. We have so many expressions in the western world that riff on this wisdom: having a North Star, stay true to yourself, stick to your knitting, be comfortable in your own skin, you do you, etc.

It seems to me that being confident in who we are, and what we like, and what we stand for, is the first step in getting out of a cycle of fear. Because if I have something inward to focus on, I don’t have to focus on an outward threat. It’s like knowing yourself gives us our mind and soul something better to do than look at the scary things around us.

Talking to my colleague reminded me of this important practice of knowing thy self.

But how?

—

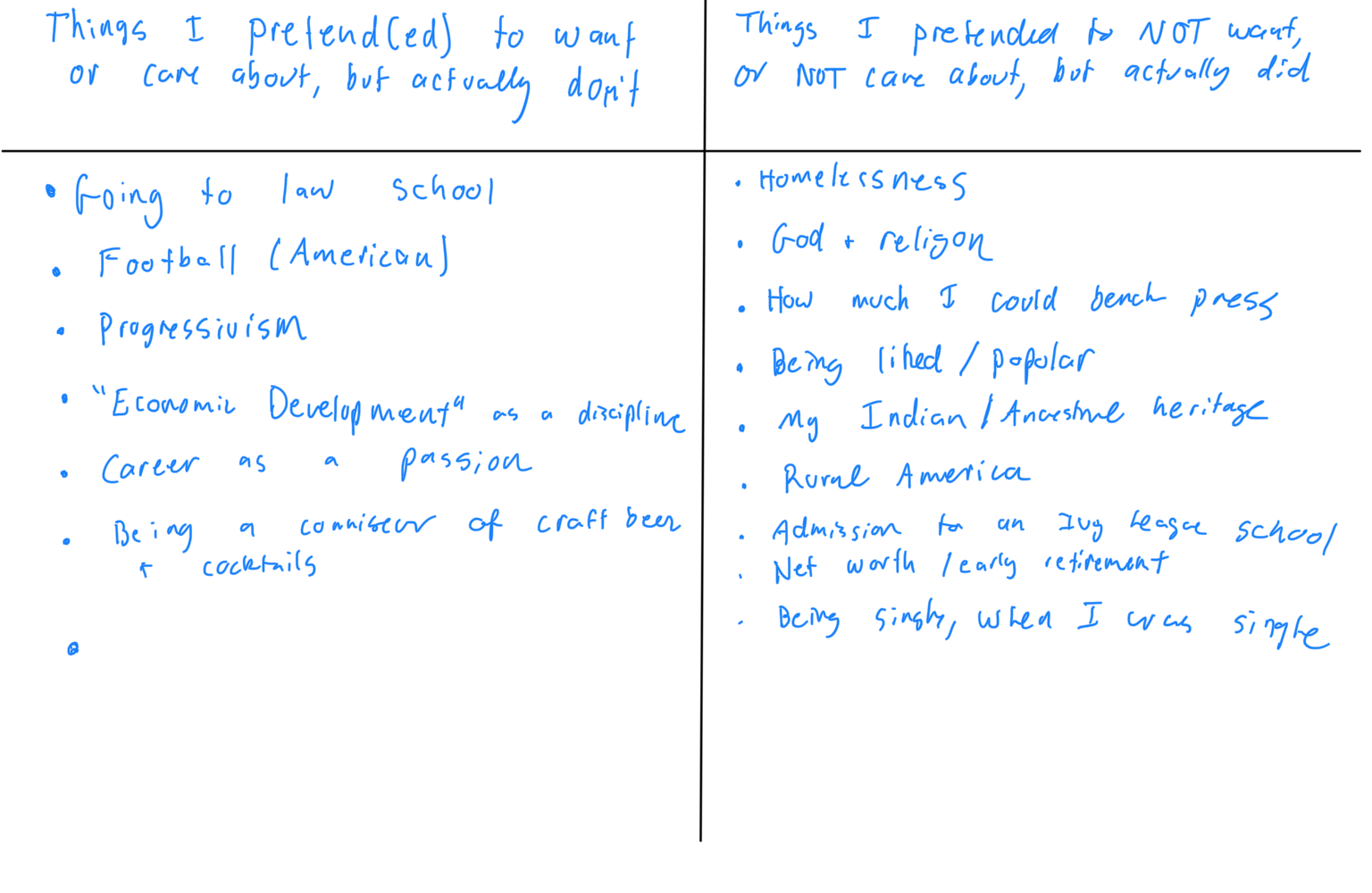

I have told myself lies. Like, big lies that led me astray of who I am. Those lies wasted my time and talent; kept my soul and mind in chains.

By bringing these lies into the sunlight, they become less infectious. And then, knowing ourselves is more possible. And then we have something other than fear to anchor our lives in.

Reflection to disinfect the lies I tell myself

1. Make a two column table on a blank piece of paper

2. Label the first column, “Things I pretend(ed) to want or care about, but actually don’t”

3. Label the second column, “Things I pretend(ed) to NOT want, or NOT care about, but actually do”

4. Answer it honestly

5. Share with someone who knows you better than yourself. Ask them: “What am I still lying to myself about?”

6. Do something different.

Moments from North Cascades

We recently returned from a few days in North Cascades National Park in northern Washington. We heard about it from a list of “underrated National Parks” and it really is terrific (and underrated).

If you have spent any time hiking and camping, these vignettes will likely rekindle memories of your own adventures in nature. If you haven’t been to one of our country’s amazing National Parks, I really recommend it.

If you get a chance to visit a National Park - even if you’ve never camped before - I really recommend it. Here’s a series of reflections from our recent trip to North Cascades National Park.

If you’ve spent any amount of time hiking and camping these will probably feel familiar to you. If you haven’t been outdoors much before, I hope you find something in these vignettes that will make you want to plan a trip.

I am angrier now than when we started the day.

After all the difficulty in getting here - canceling the first few days of our trip because of a Covid exposure, the early flight, the late night packing, and all the frustration I’m already holding in my shoulders because of our daily grind - I wanted to be on the road out of the city already. And yet, the camping store doesn’t have fuel for my backpacking stove. And I feel like I’ve taken every left turn in Seattle to go three blocks. The kids are jet lagged and haven’t napped.

I have spent weeks anticipating the familiar, friendly feeling of hiking boots laced up around my feet, and having my breath taken away by the mountains, lakes, and forests I’ve been reading about. And we’re still hours away.

The drive was more spectacular than I even expected. This is one of my favorite parts of any trip to our country’s National Parks - the approach. I remember the desolate, exhilarating, trek across the Mojave into Death Valley. And the winding approach past Moab, ducking and dodging the towering rock faces into Canyonlands. And my favorite, the most beautiful drive I’ve ever done, through barely touched wilderness into Denali. Getting there is part of the dance, the adventure. It is a chase and a tease, building anticipation the further you go. And as we traverse each mile, the booming mountains and the songs of the whistling trees and lyrical creeks draw us in, luring us more deeply into the Cascades.

It is later than I hoped, but we are here. The tent we tested in our backyard just yesterday is ready for a crisp overnight sleep. We are dressed and have our supplies in the bright green day pack we usually only take to Palmer Park, Belle Isle, or Mayberry State Park, Bo is wearing the bright pink socks he picked out at REI for the trip. Myles is on my back in the baby carrier he’s almost too big for now. We are on foot, trying to salvage our evening with a short hike before dinner. I’m desperate to settle the itch for the trail I’ve had all day. We heard there was a short hike with a vista near the visitors’ center so that’s where we go.

And as we turn the last bend of the boardwalk, we see it - it’s the Pickett Range. Robyn and I see the boys - right as we get the same feeling of awe and wonder ourselves - experience the majesty and beauty of nature for the first time. We all exhale and soak in the full frame we have in front of us. I am starting to cry while I write down this memory, just as I did when we lived it a few days ago.

We just survived our first night in the tent with two kids, barely. We are on the trail for a morning adventure before nap time. I ask Robyn if I can take her picture. I want to remember being here together. I am thinking back to our honeymoon, when we spent 2 days - just us and the trail - at Mammoth Cave National Park before continuing to Nashville. I am grateful for our marriage, our family, and how we’re spreading our love of outdoor adventures to another generation. I always feel whole when we are together, but my cup is especially full as I snap the photo of her.

I did not grow up with siblings. But even though I forget it sometimes, our boys are brothers. I see it with my own eyes, vividly, as they scamper together down the trail hand in hand. I remember back a few days earlier, when Bo asked Myles: “Will you be my best friend?” We will have many moments during our few precious days here, to remind me of something important: this was worth it. All the setbacks, all the discomfort of travel, all the preparation - all of it was worth it for the three days we had. The chance to visit a National Park - the rare gems of our truly beautiful country - is always worth it.

For the first time since we arrived, we turn left out of the campground into State Road 20 - we are heading home. Robyn and I are holding hands as we weave west back to Seattle alongside the Skagit River. Myles points out the window and says his new favorite word, “mountain”. As we talk to Bo about the past 3 days and how we can plan another trip soon, he asks us, “Can we come back to Cascades National Park?”

Robyn and I smile at each other and I remember something she said a day earlier, after we descended after only making it halfway up the Thunder Knob trail - “we’ll be telling stories about this trip for years.” In that moment I have an uncommon amount of gratitude - for nature, for our family, for our marriage, and for the National Park Service - because I know deeply in my bones that she’s right.

Adult Bullying

I have such inner turmoil about feeling like I’m lagging behind my peers, in terms of career development. It’s totally irrational and stupid (and I know it), but I still feel it. I always thought it was just it was social comparison and some inevitability of human psychology.

But now, I’m wondering whether it’s just a response to the kind of covert bullying we adults torture each other with. If career angst is a response to the stimulus of feeling bullied, that’s actually a good thing. Because we can choose to respond differently.

There are four basic responses to being bullied: confront, ignore, retreat, and assimilate. Being bullied is a terrible thing, so basically everyone responds to it in one way or another.

Confronting a bully is what most of us aspire to do, like in the movies. In a moment of glory, we resist the bully’s actions and once we stand-up to them, they stop. This is hard, especially if you have no support or real power.

Ignoring a bully is also hard. When choosing this response we just keep doing what we’re doing and don’t give the bully the satisfaction of a response, despite the harm they’re inflicting on us. Eventually, they move on to a more participatory target.

Retreating is when we fold back into our crew and go back to our circle of support. Retreating is not necessarily “weak”, it’s simply a strategy of avoidance and getting back to a community where we’re protected. Strength in numbers, I suppose.

Assimilating is the, “if you can beat ‘em, join ‘em” approach. If the beefy football player is your bully, become an even beefier football player. If the bully is cruel and wicked toward the weak, assimilate to also become cruel and wicked. In this scenario you get out of being bullied by becoming a bully.

What I’ve just tried to invoke are the feelings we had in middle and high school, when basically all of us were either a bully to someone, bullied by someone, or both. Adolescence is where we see explicit bullying, at least in America.

But I don’t think we leave bullying behind once we graduate high school. Even if it’s not as overt, I’ve come to see that there is adult bullying.

How is talking about a colleague’s flaws and failings when they’re not around that different from trashing how someone was dressed at the Homecoming dance? Put downs are put downs, no matter how old we are when it happens.

How is flashing images of an expensive house or expensive hobbies that different from lifting weights to get big biceps and wearing a varsity jacket (literally everywhere)? Asserting dominance is asserting dominance, no matter how old we are when it happens.

How is yelling at a customer service rep on the phone that different than picking on the “unpopular kid” in the cafeteria? Verbal abuse is verbal abuse, no matter how old we are when it happens.

How is humble bragging about the big promotion we got, that different than humble bragging about who we made out with over the weekend? A pissing contest is a pissing contest, no matter how old we are when it happens.

I used to think that the reason why I’ve been obsessed with career trajectory, my resume, Google self-search results, and all that stuff is because of social comparison and this basic human need to keep up with the Joneses or something. I thought it was just “psychology.”

But I’m wondering now if it’s just a response to adult bullying. Like, maybe I feel bullied by what other people are saying and doing and I’m trying to make the pain stop by getting a promotion of my own.

Thinking of my existential angst about career as an assimilation response to bullying instead of an inevitability of human psychology is a very different ball game.

Because if I’m intentional about it, I can choose to respond to adult bullying in someone other way than striving to become an adult bully myself. I can choose to respond differently.

The Ballet Mindset

Ballet, and dance in general, is one of my great loves. Reflecting on it as an adult, I’ve come to appreciate it as more than just a performing art. The craft of ballet is one that cultivates a mindset of joy, grace, and intensity.

I wanted to share a bit about ballet because I’ve come to lean on it as an alternative to the cultural mindset of dominance, competition, and winning at all costs.

Training as a dancer, particularly in ballet, influenced how I move through the world. The way I’d describe it is a “joyful and graceful intensity.”

Ballet cultivates this mindset in a dancer because…

Ballet is emotional. In ballet you are expressing, through movement and the body, deep emotions. Ballets tell moving and powerful stories, that dance on the boundaries of human experience. Telling those stories takes a special type emotional labor, because expressing emotion and telling stories without dialogue is a unique challenge.

Ballet is technical. Dancers don’t seem to float, soar, and spin effortlessly because they’re “just born with it”. It’s practiced and drilled. As a ballet dancer, I spent almost half of all my classes at the barre, developing technique. And during a ballet class the first skill you practice, over and over, is learning is to plié - which is literally just learning how to bend your knees. Seriously, as a ballet dancer you spend a remarkable amount of time learning something as simple as bending your knees properly. And from there it builds: it’s technique around pointing toes, posture, moving arms, jumping, landing from a jump, body positioning, body lines, turning, and so on.

Ballet is athletic. Miss Luba, my Ukrainian ballet teacher, used to say that as a dancer you could be doing the hardest jump, lift, or arabesque, but to the audience it always has to look easy. To do that takes tremendous strength, power, body control, and endurance. Ballet is so hard on the body. Of all the sports I ever played, a really tough ballet class was a special kind of physical and mental beatdown. If you don’t believe me try it. Stand on your toes on one foot, hold your arms out from your shoulders, or just jump continuously and see how long you can do this without stopping or grunting in anguish. There’s a reason why ballet dancers are jacked.

Trying to be emotional, technical, and athletic all at the same time takes intense focus, To boot, ballet dancers cannot just go through the motions or rage uncontrolled through a recital. They must perform: physically, mentally, emotionally, artistically, and technically. And the ballet dancer’s craft shapes their mindset into one of joyful and graceful intensity.

As Americans, our culture often emphasizes winning, aggression, strength, dominance, and power. At extremes, I wonder if that encourages, bullying, hostility, and violence.

Being king of the hill isn’t the only way to live and make a unique contribution. It’s one of many choices.

For me moving through life with a ballet mindset, rather than one of dominance, is a contribution in itself. Because acting joyful and graceful intensity is what brings beauty into this world.

I’m grateful to my teachers and dance peers. Because of them, I know that a seemingly paradoxical orientation of joy, grace, and intensity is even possible.

Surplus and Defining “Enough”

Unless I define “enough”, surplus doesn’t exactly exist.

The idea of surplus is simple, you compare what you have to what you need. If you have more than you need, surplus exists. The concept of surplus is often linked to money or material resources, but I think of it in terms of time and energy.

I’ve thought about the question, “What am I doing with my surplus?” before. But I’m realizing that I’ve missed a more fundamental question: “How much do I need? How much is enough?”

To a large degree, how much we need is a choice.

If I wanted to live by myself and grow my own food off the grid for the rest of my life, I could probably retire tomorrow. If I didn’t want to grow in my job, I probably wouldn’t have to work as hard as I do - I could coast a bit and do the minimum to avoid being fired. If I didn’t care about the health of my marriage or raising our children, I probably wouldn’t have to put as much energy in as I do. If I didn’t have such a big ego, I probably would spend less effort trying to gain social standing. You get the picture.

Defining the minimum standard - after which everything else is gravy - is what creates the construct of surplus in the first place. Because if what I “need” only requires I work a job for 25 hours a week, I now have created 15 additional hours of surplus, for example. If it’s unclear what my bar is, it’s hard to know if I’ve cleared it. Until I define that bar, I have no basis for measurement. Defining what “enough” is is half of the surplus equation.

And I want to know if I’ve cleared bar. Because once I have, then I can use that surplus for things I care about - like traveling, leisure, writing, serving, prayer, time with friends and family, gardening, learning something new, exercising, whatever.

I’m realizing my problem is that I haven’t really defined my minimum standard, so I don’t really know if I have enough. And because I don’t know if I have enough, I am stuck in this cycle of grinding and grinding to get more even though I may not want or need to.

This uncertainly leads to waste. If I do have enough, but don’t know it, I might be wasting my time and energy working for something I don’t want or need. If I don’t have enough, but don’t know it, I am probably misdirecting my time and energy on things that aren’t high priorities.

Either way, if I’m not clear on what I need and how much is enough, I’m likely wasting the most precious resources I have - my time and energy.

For so long I’ve blamed the culture for my anxiety around career and keeping up with the Joneses. I figured that it was things like social media and societal pressures that made me engage in this relentless pursuit of more. But maybe it’s really just on me.

Maybe what I could’ve been doing differently all along is get specific about how much is enough. Maybe instead of feeling like I have no choice but to be on this accelerating cultural treadmill, I could really just turn down the speed or get off all together.

These are some of the questions I haven’t asked myself but probably should:

How much money do we really want to have saved and by when?

What is the highest job title I really need to have?

How respected do I really need to be in my community? What “community” is that, even?

How much do I want to learn and grow? In what ways do I really care about being a better person?

What level of health do I really want? What’s just vanity?

What creature comforts and status symbols really matter to me?

At what point do I say, “I’m good” with each domain of my life? What’s the point at which I can choose to put my surplus into pursuits of my own choosing?

Only after defining enough does it make sense to think about the question of “what should I do with my surplus?” Because until I define “enough”, whether or not I have surplus time and energy isn’t clear. And if it’s not clear, I’m probably wasting it. And surplus is a terrible thing to waste.

The unmeasured life

Life defies measurement. Trying to measure it has kept me in a state of unpeaceful flux.

The way I think has been a bit of a trap, at least historically.

I have a lot of angst, shame even, that I am not as professionally successful as my peers. No matter how hard I try, even on vacation, I can’t get away from thinking about whether I measure up - either to my peers, or even to the career trajectory I thought I would be on.

Which is all foolish, by the way, because I don’t even care that much about career. Where I intend focus most of my energy is family, community, and character. And yet, because I have been trained in the realm of organizations, business, management, and leadership I am always going back to that foolishness of measuring myself up.

Because that’s what many of us who are professionals by training - whether in business, law, public service, health, athletics, or anything else - do. We measure things and maximize them, because in our professions the result is what matters.

Again, for me this thinking is a trap. It’s the relentless pursuit of more, and my ego wants me to be cooler, professionally speaking, than I am. And if I use my peers (and my own egotistical visions) as a yardstick, I don’t measure up to that expectation.

And so I try to cope, probably in a way that’s irrational. Because I try to cope with the fact that I don’t measure up professionally, by counting the ways I think I measure up in other domains. I always think - “I have a loving marriage and family. We have a dog. We have a home we like. I get along with my parents. I have a BMI that stays at a healthy level. We have kids with good hearts. I may not have a fast-track career, but I measure up. I measure up. I measure up.”

And that is the trap. Measuring my non-professional life is the trap. Because what I’ve realized is that, my life is not an enterprise judged by it’s measurable results. My family is not a business unit. It isn’t in the nature of a soul to be benchmarked, standardized, or process-mapped to ensure it has optimal peacefulness.

And by trying to “measure” my non-professional life, I’m propagating this pernicious, unsustainable mindset that my life must be measured. I’m locking myself into a mindset that keeps me anxious and makes me live in a constant state of needing to quench my egotistical desires.

The whole mistake I’ve been making is to try applying the principles and methods of my profession (i.e., focusing on measurable results) to my life. I can’t live at peace with my own thoughts if I try to replace the measurable career results I’m not achieving with an attempt to measure love, family life, children, happiness, faith, peace, experiences, stories, or moments of ordinary joy. Doing what I’m doing locks me into a place where I’m always on the verge of a stomach ache. What I need to do instead is let go of measuring my life.

Because life is something, I think, that cannot be measured.

The problem is, I want so desperately to be able to grab hold of something. My lesser self wants some morsel of incremental progress to remind me that I’m not wasting my life. Some mile marker along this long walk that makes concrete the messy path of life I have ahead and the road I have already traversed. Some interim report card that shows I am doing well at living out the life and that I won’t fail the final exam on my deathbed.

And this is the trap. It’s akin to the plight of Sisyphus. He was rolling a rock up a hill that could never be summited, and I trying to measure my life - something that is not only immeasurable, but that defies measurement.

But after all these years of acculturation and training - how do I resist the near-natural urge of measurement, and instead live an unmeasured life?

I admit now that I should not try to look for mile markers, or anything that charts progress along a fixed path toward a final destination. Because after all, my life has no fixed destination, duration, distance, or pace. Life defies measurement.

But perhaps there is some consolation.

If we know how to look for them, there seem to be where God gives us a window into our inner-compass, to remind us whether we are heading north toward home, or whether we have veered from the righteous path.

The other day, I had one of these moments. Myles got into a spat with his older brother. He, as a 1.5 year old occasionally bruises his nearly four year old brother. And Bo was sad. And we said, “Myles, that was not nice. It is not kind to hit your brother. You need to say sorry.” And he pondered for a minute. Bo gave Myles a glance back, unsure whether Myles was heading in his direction for reconciliation or to continue the bruising.

But there Myles went, arms outstretched, toward his brother. And it was, without any words or babbles, as sincere of an embrace as I’ve ever seen between two people. It was a moment where my soul reminded my body that it was still in there. It was a moment where God gave me a look at my inner-compass, and it reminded me I was on the right path.

I never know when those moments are going to come, and sometimes they’re reminders that I’ve veered. But when those moments happens, I am consoled. Because even though they aren’t the mile markers of progress that my egotistical self craves, they are reminders that I am on the right path, heading toward home.

And as much as I would like to, I can’t put moments like that into some sort of scorecard or graph. Those sorts of moments, where God shares the light see my compass, and reminds me to look, defy measurement. There are so random and nuanced, they can’t be counted or formed into a pattern.