Brain Drain Follow-up: Reasons Why Companies Obsess Over "Attract and Retain"

In my last post, "Focusing on Michigan's Brain Drain Is a Miss", I criticized the common dialogue in our state about "brain drain" and its emphasis in local politics. After thinking on it a bit, I'd like to offer up a few reasons why attraction-retention programs seem to be en mode and how we might use different approaches to do something different, namely advancing comprehensive policies focused on developing vibrant cities. First, let me clarify my position. I don't disagree that brain drain is something worth mitigating. What I criticize are programs that are narrowly focused to combat brain drain via attraction-retention approaches. These "attract and retain" programs that might provide generous subsidies for relocation or create [poorly designed] job databases seem to be the wrong approach. Rather, we should focus on creating strong communities and vibrant cities that people want to move to and that increase the likelihood that innovative job growth occurs. In other words, we should be creating amazing opportunities for talent to develop (so that people want to come here over other places). To paraphrase my (supremely intelligent) friend Chad: it's not that you either combat brain drain or build great cities....building great cities is the best way to combat brain drain.

Anyway, the thrust of my point of view on why folks might obsess over things like job boards, living incentives and other attract and retain policies: employers focus on the costs that they bear and make decisions based on those costs. This is reasonable.

Employers bear a lot of costs when acquiring new talent. One such cost is a search cost - the cost of finding talent and hiring. Another cost is a relocation cost - the costs of getting someone to move from one place to another. A third cost is retention cost - the more people leave your company, the more you have to repeat the costly process of hiring. A fourth cost is training cost - you have to use time and resources to give hires the skills they need to succeed on the job. There are more, too. I'm just generalizing some of the most understandable and commonly discussed costs. These costs are all real, hard, dollars, and do not even include the costs of morale, lost productivity, etc.

Because these costs are the "direct" costs of talent, that is the costs of talent management that directly hit an organization's bottom line, organizations actually care about them. These are costs you can't argue with. Organizations, particularly businesses, usually make decisions on these costs because they can see them directly. That's what is visible on a financial statement and thus what shareholders and analysts measure a business on, generally speaking. Money talks, but more importantly it also tells a story about the economic realities of that business. That story, as told by financial statements, is how decisions are made.

So it should be no surprise that we see the traces of Detroit's regional talent strategy - if you could call it that, it's not very strategic - focus on some of these things (the impact on costs are in parentheses):

- Job Boards like MI Talent Connect (reduces search costs)

- The Live Downtown Program (reduces relocation costs)

- Live Work Play Initiatives (you could argue that these might affect retention costs)

Now, let's look at some of the costs and revenues that are NOT directly measured by employers (and some snarky conclusions in parentheses related to the role of business. Looking through the lens of business is critical because business is current THE power player in Detroit city affairs).

- Transportation Costs - employers don't pay to get their people to work (So should we be surprised that public transit isn't robust in Detroit?)

- Cost of Basic Education and Skills - employers don't bear the cost of their people learning to read, learning calculus, or going to college (So should we be surprised that scant attention is paid to really bolstering the performance and affordability of public K-12 schools or universities? To be fair, the business community is starting to act in this arena)

- Opportunity Cost - employers don't measure the money they could've made if they were more innovative (So should we be surprised that we don't have more of an emphasis on density, cultural institutions, and public dialogue - i.e., some of the things that really drive people to innovate within a city?)

I don't think we should be surprised with the attract-retain strategies that we have, because the business community is simply acting in its own interest - to reduce its direct costs of talent. And this is a problem, I think, because some of the stuff like job boards, the Live Downtown Program, or so called "Live Work Play" programs don't seem to be moving the needle on Detroit's resurgence (in a broad sense), by themselves. My guess is that the attract-retain strategies are unsustainably expensive in the long term, as well.

I think the strategy of building strong communities and vibrant cities is attractive for two reasons: 1) it addresses the direct AND indirect costs/revenues I've listed, and, 2) it has spillover affects that affect more than just the economic viability of companies...it also improves social welfare (happiness, health, etc.)

How strong communities and vibrant cities affect direct and indirect costs/revenues of talent

Here's some qualification of my assertion above - that creating great cities addresses direct and indirect costs/revenues:

- Search Costs and Relocation Costs- If you have a great city, the city PULLS people interest with less effort on the part of individual businesses. Thus it takes less time, effort, and money to find qualified candidates who want to work in Detroit. Consequently, employers have to pay less of a premium to attract talent

- Retention Costs - If the city is strong and there are more job opportunities and people actually want to live here, there's less turnover (i.e., there's less of a "I'm in Detroit until I find a job in Chicago" effect). If more opportunity produces a spike in turnover, it probably means talent quality is at least higher and there is quality talent to fill openings

- Training Costs - Vibrant cities are places where people can learn from other smart people. There are lots more opportunities to learn and grow as a professional as a result, like skills-based volunteering, talks, or workshops

- Transportation Costs - Cities with transit systems provide an opportunity to lower the total overall cost of transportation for residents, both in terms of time, money, and the headaches of traffic. It's a form of compensation, in effect, which lowers the cost of living and allows employers to pay less. More importantly, it opens up new talent pools because more talent can move within the city

- Basic Education Costs - Strong communities and vibrant cities probably educate their kids better. I'm not an ed expert so I'm not supremely confident about this, but that's my intuition. At very least, strong communities probably give the opportunity for a better education to a larger portion of its residents

- Innovation Opportunity - When smart people bump into each other (this is obviously simplifying the issue, but this is a whole research paper in itself, but don't worry, one is coming) is when innovation happens. That's when value creation opportunities happen. That's why there's this dialogue on cities = innovation. If people in the city are more innovative and good at innovating, that probably translates into individual firms that already exist as well

Actions to consider

Let's assume for a second that strong communities and vibrant cities are a better option than some of the "attract and retain" policies currently used in Detroit. Even if that's the case, how do we actually get there? This, again, is a blog post in itself, but let me suggest a few ideas which form an ad-hoc list for considering this question:

- Talk in a language business understands - businesses are driven by what their financial statements say (because that's what shareholders care about...I think this is foolish, but let's assume we can't change this immediately). So, give them a case that they can take to their shareholders. We need to create a business case (detailing revenues and costs) for why a comprehensive strategy to bolster communities and cities is the best option

- Strengthen other institutions - other institutions, like government, are often better suited to address to broad public concerns (like creating vibrant communities). If we strengthen civic institutions to displace the headwinds in civic life created by business, the public sector can lead the charge to create strong cities. In Detroit, maybe this means being more active as a citizenry or building up the capacity for transformational change within city government

- Recruit big players - if we have a big player in our ecosystem that's not accountable to shareholders, they can be a leader in creating a vibrant city which provides political cover to other, smaller players. That way, the smaller players could use the big player as an example when justifying decisions to their own shareholders. I suspect Dan Gilbert is having this effect in Detroit - he can do what he wants because he's wealthy and his own boss, giving other community leaders increased tacit permission to follow suit

- Focus on our broader narrative - I alluded to this in a previous post - [link]. If we have a broader narrative of why we want to have a city, it allows people to create a moral case for change, instead of just depending on a cost/benefit analysis

I welcome your feedback. This issue is debatable and important.

Focusing On Michigan's Brain Drain is a Miss

The conversation about brain drain in our state is common and (sort of) well researched. This entire discussion, though, is problematic. Averting brain drain via direct programs is the less effective (and probably more expensive) strategy. Creating strong communities and vibrant cities is a better course of action. Breaking down the issue

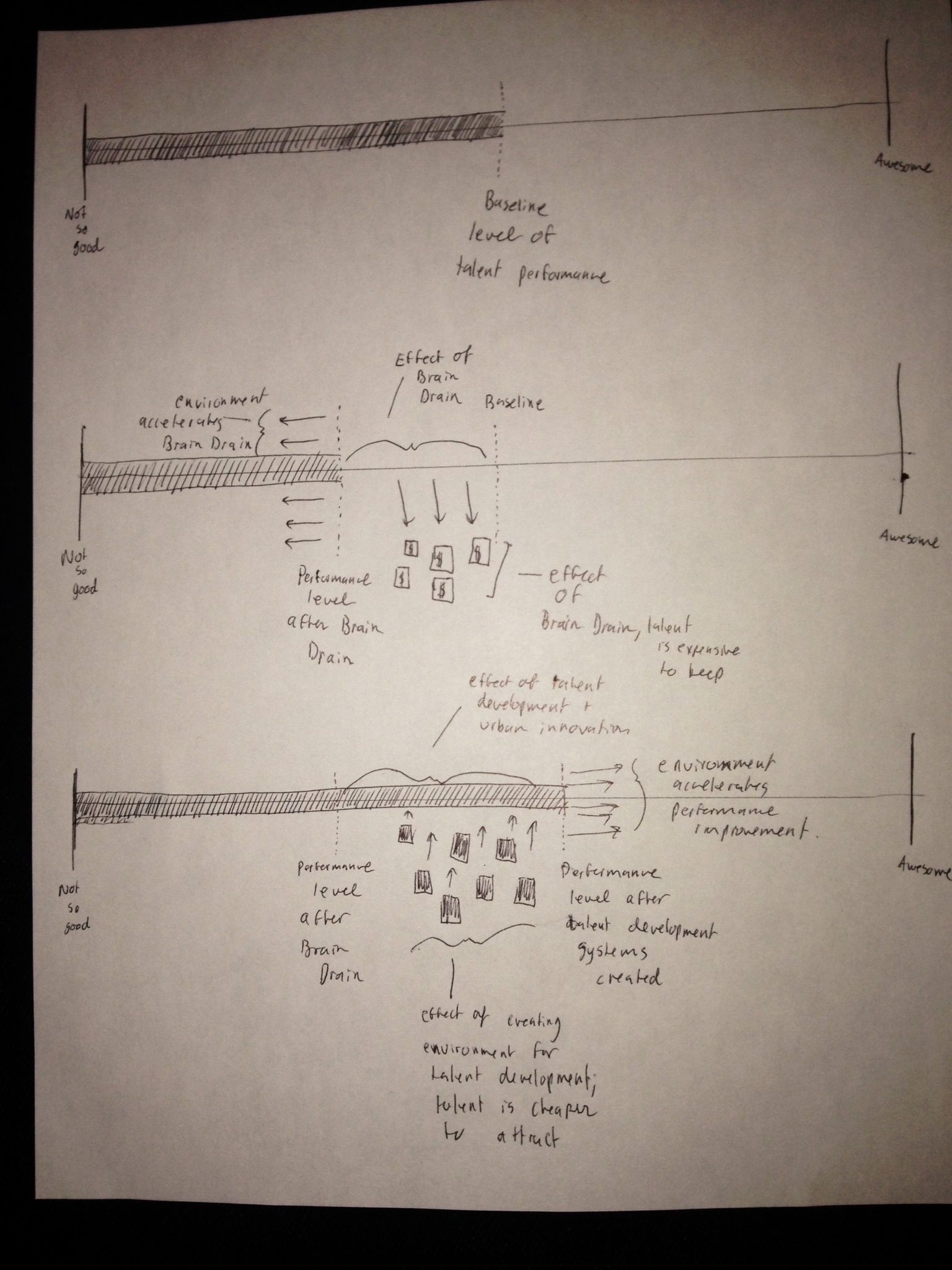

Check out this chart below. Give it a look over and then I'll explain what I am trying to convey. A quick definition - the way I "talent performance" is this: talent performance is the product of talent quality and talent quantity --> Talent Quality x Talent Quantity = Talent Performance.

These axes are representations of the level of talent performance in Detroit and the State of Michigan more broadly. The bigger the bar, the better our talent is performing and the better off we are with regard to talent. For discussion's sake, let's say the top graph is the current level of talent performance. The baseline level there is represented by the dotted line.

The middle graph represents brain drain. Basically, in brain drain people leave the state, which lowers our overall level and quality of talent. These departures decrease the level of talent performance in the state, hence the smaller bar. The distance between the two dotted lines is the effect of the brain drain. Now, as people are leaving the state, lawmakers and business leaders are trying to respond by wooing talent to prevent them from leaving, or wooing talent outside the state here.

This is a reasonable strategy, except that it's a foolish one. Wooing talent is very expensive. You have to give departing talent lots of resources and you have to 'wine and dine' them, so to speak. You have to invest lots of money in programs and you might even have to subsidize their wages. All this is very pricey.

What's worse is that all this time and money spent on wooing talent doesn't really have ripple effects to the rest of the citizenry. If you woo someone to Michigan by paying them more, for example, it doesn't make a neighborhood in Detroit directly better, the only person that benefits substantially is the person who was wooed. The dollars you spend don't have effects on other things to make other parts of society or other people better, in a meaningful way. And, if you spend money to woo someone, that person may never be fully satisfied unless you keep wooing them which burns even more of hole in the state's pocketbook. Just like subsidies for other products and services, once you provide a subsidy, people start to expect it.

The bottom graph, demonstrates what happens when creating an environment that develops talent and gives it the space to grow on its own. Said differently, this is a representation of what happens when you make communities better and make cities more vibrant. By improving the environment for talent, the talent that is already here gets more effective and performs better. The baseline level of talent performance increases; the bar gets bigger without more people needing to be here. Moreover, when you create a great environment, people come here on their own. People want to be part of excellent environments so they find their way here because they see opportunity, prosperity, and happiness. You don't have to woo them with one-off programs or compensation packages. This is much cheaper than rolling out the red carpet to bring people to Detroit.

Make no mistake, building communities and making cities more vibrant isn't cheap or easy in the absolute sense. In fact, it's probably expensive and really, really hard. But it's still better than wooing talent in an ad-hoc fashion because the dollars spent to make cities and communities better has all sorts of unrelated positive effects. The people in the community probably become happier if their community develops. There's probably lower levels of crime. People are probably more educated and involved in government and other aspects of civic life. By building communities and making cities more vibrant, the dollars spent provide returns years and years later. The people being wooed to come here are definitely NOT the only people who benefit substantially from the effort. On the contrary, when you build communities and cities, the whole community benefits.

Here's the takeaway: we should be focused on creating a great environment for talent by building up our communities and creating vibrant cities instead of trying haphazardly to prevent brain drain at high cost. That's ultimately what will be more beneficial for the city and state in the long run. Trying to combat brain drain directly is expensive, and it might not even work.

Moreover, this is possible - saying, "it's too hard" or "we don't know how" is a poor excuse. The work I was part of at the Center for the Edge is a great piece of research explaining the framework for thinking about how to create innovative, performance-improving environments. Also, look out for a report coming through from Detroit Harmonie soon. I can't really discuss it yet, but it's cool stuff.

Let's get serious about building great communities instead of wasting our time on conventional wisdom of attracting talent solely to prevent brain drain. Quite literally, if we build great communities and vibrant cities talent will come. So let's focus on that.

---

Holler at me with stuff I should rehash. This is a pretty intense topic.

Why Are We Transforming Detroit? (Public Transit As An Analogy For Purpose).

The other day, Robyn and I were discussing how kids in Detroit get to school. Some of her students ride 2-3 buses just to get to her school, for example. I imagine that kids across the city choose schools because of accessibility and transportation options. In fact, I think it's reasonable to assume that's the case with many students across the country. Heck, a lot of people I've talked to in life choose lots of the places they visit based on accessibility and transportation, whether it's bars, churches, hospitals, or places to work. [Note: this post isn't a rant about public transportation in Detroit. I'm merely setting up an analogy to make the real point I want to convey easier to understand.]

Let's take the example of Detroit students going to school. What happens if their school moves to a new building? Many of them may have to stop going to the school because it's no longer possible for them to go there, or maybe it's too much of a hassle to take additional buses to get there. Why?

One reason is because the bus system in Detroit isn't frequent or widespread enough to be worth the cost and hassle. Take a look at the bus system maps for Detroit and Seattle (links below), for example. Notice how it would be really hard to get across the city (i.e., moving in and around the city's longstanding neighborhoods outside of the Woodward corridor) unless routes were extremely frequent (I'm obviously making assumptions...I don't have great data):

Here's a takeaway for Detroit - people who probably need buses to get to work and get around the city probably have a really hard time doing so. This is an opinion, but I'd argue that people in the neighborhoods need transit the most and that a transit solution would improve these citizens' lives the most.

Enter M1 Rail

One of the exciting projects of this summer was groundbreaking on the M1 Rail Project which will connect Downtown and Midtown by streetcar. Which is great. I'll love it when done. But M1 only benefits you if you're going to be Midtown and Downtown a lot. If you're not a wealthy Detroiter who lives in Midtown/Downtown or frequently goes to Midtown/Downtown (i.e., if you spend a lot of your time in the neighborhoods I mentioned above), the M1 rail probably won't benefit you very much.

This might also be fine. But it raises a very important question in my mind: why do we want public transit anyway? Have we even articulated what we're trying to accomplish by having public transit? I feel like if you asked people this question before the proposal of M1 rail, there would be legitimate discussion between some of these "statements of purpose":

- Build light rail for its own sake because it sounds cool and will legitimize Detroit to people outside its borders - in this case you'd probably build rail

- Stimulate economic and civic activity by helping people who don't have other options participate in the economy and civic society - in this case you'd probably build a bus system

- Make Midtown/Downtown more vibrant (spin: benefit wealthy residents who want to live in a walkable community) - in this case you'd probably build a streetcar line

Here's the point: I have no idea why we wanted to build public transit in the first place. Because this underlying reason for taking the action of building public transit systems, I'd call this "purpose", is unclear, do we even know if we're achieving our goal? By funding a streetcar line, is the M1 rail project fulfilling the right need? Products and services a company or city chooses to provide can vary widely depending on the need it intends to address and how that need is articulated.

A major public infrastructure project ought to have a clearly identified and articulated need, I think. Doing so, would helps agents design the right product/service and be held accountable to results.

---

Detroit's Transformation: why are we doing it?

Similar to the M1 rail example, I raise the same question for Detroit itself: why do we want to make Detroit better? What sort of community are we trying to create, and why? Is it for the purpose of:

- Generating lots of wealth and prosperity for all citizens?

- Creating a cohesive community that has minimal conflict between different types of people?

- Helping citizens have lots of fun?

- Facilitating robust civic discourse?

- Improving Detroit's public perception to the rest of the country?

- Allowing talented people to accumulate lots of power and wealth if they are smart enough to do so?

- Bolstering cultural and artistic expression?

- Providing every citizen with the agency to reach his / her goals?

Which of the statements of purpose do we really care about as Detroiters? Detroiters? One might say "all of them", but that's foolish. Our city cannot be everything to everyone, nor could any city be everything to everyone. Even if we tried, there would inevitably be times where these different priorities would be in conflict or require tradeoffs. In those cases, which statements of purpose do we prioritize more?

(Note: this is often conveyed by leadership or an organization, like a mayor. This idea of conveying a common purpose that people buy into will be huge for the next mayor.)

Making Detroit better will require extreme amounts of collective action. In my experience, collective action requires shared purpose (not to mention shared vision for how this "purpose" looks like when you actually start building stuff). The way I see it, lots of people have lots of different ideas for what the purpose of transforming should be and why we should transform Detroit. If that's the case, collective action will probably fail or have lots of conflict.

Before we start trying to rebuild Detroit, we need a clear picture on what sort of community we want Detroit to be, and why. If not, I don't think our transformation efforts have a good chance of persisting.

The Many "Currencies" of Social Impact

After the fun commentary people had on one of my previous posts, "Why Business Must Do Good" (Published on Detroit UIX here, or this blog here). I wanted to go a little bit deeper on one of the concepts I introduce: different types of value. I'd like to try building up more knowledge on how those types of value might be stored or manifested in society. By figuring out how those types of value are stored, perhaps we can better measure them. If we can better measure them, maybe we can figure out how to create value more easily. ---

Currency was a pretty big innovation in human society. All of a sudden, we were able to store value in an object, which made it easier to exchange goods and services. For example, if you were a corn farmer, you no longer had to barter with bushels of corn. You could exchange your corn for currency and then use that currency to purchase other things. Because currency was accepted everywhere and didn't spoil the way corn did, it was very useful.

Currency, say US Dollars or Euros, are a method of storing economic value. But, as I pointed out in a previous blog post, there are different kinds of value. I'll try to brainstorm (at least as a first attempt) the different "currencies" that can be used to store different kinds of value: social, spiritual, and civic value. If the analogy holds, the currencies of value could be used to increase, build up, or expand that type of value if you add effort. For example, money (a "currency") + effort + ideas that can make money (another "currency") = economic value.

I'll begin by articulating economic value, and what some other stores of value might be.

The point of economic value is to meet material needs and exchange goods and services. This is the arena which addresses humanity's need to have basic human needs and comforts. As a result some currencies of economic value might be:

- Money - the more money you have the more goods and services you can exchange for

- Physical Assets - Stuff that allows you to make other things

- Contracts - Promises that people will pay you for something you've given them

- Ideas that can make money - think of patents, it something that will probably give you economic value in the future

Basically, anything that you'd find in the "assets" section of a company's balance sheet is a store of economic value.

The point of social value is to have an enriching community where people feel good. This is the arena which addresses humanity's need to have happiness. As a result, some currencies of social value might be:

- Relationships - connections to other people makes people happy

- Healthy bodies - being in better physical shape makes individuals better

- Environment - it's not pleasant to live in a place that's dirty or polluted

- Knowledge - an ability to understand how the world works

- Activity - activities are opportunities to not be bored

The point of civic value is to have interactions between people be peaceful and create institutions in such a way where it allows people to reach their goals. This is the arena which addresses humanity's need to have agency. As a result, some currencies of civic value might be:

- Freedom - preclearance to do what you want and pursue your goals

- Rights - basic protections from institutions that people can claim

- Integrity / Trust - people keeping their word and acting consistently with their values

- Shared understanding - a common view of the world and acceptance of others

- Fairness - knowing that rules will be applied consistently and equally

- Institutions - systems and processes which govern interactions and provide heuristics for how to get along in civic life and discourse

The point of spiritual value is to have an understanding and acceptance of our humanity. This is the arena which addresses humanity's need to have meaning. As a result, some currencies of spiritual value might be:

- Inquiry - the ability to explore things and immerse yourself in them

- Expression - the ability to project who you are

- Wisdom - an ability to understand what life means

- Peace - feeling okay with who you are and your surroundings

- Reflection - being able to connect with yourself and understand yourself

Wrap up

Anyway, the whole point of this post is to get at the major assets (for a person, organization, society, civilization, etc.) required to have different kinds of value. The way I see it, by gradually getting deeper on value and how it's created, we might be able to start measuring value better. For example, say we determine that one of the assets of social value is indeed healthy bodies. Then we can start to ask, "what are the key indicators of healthy bodies?" Say we determine one of the key indicators is adequate exercise. Then from there we can create programs and organizations which aim to influence adequate exercise.

Obviously I'm making a lot of assumptions about how the world works. However, one has to start somewhere in a field that hasn't been developed, and then iterate.

Future of Auto #3 - Dealers of Tomorrow

I want to intern in Detroit this summer and I’m extremely interested in things like Consumer Insights, New Product Development, Future Trends Analysis, and Strategic Planning. Basically, I like building and launching new things. Seeing as how working in Auto is the likeliest of these routes (though not exclusively), I figured I’d see if I could actually come up with visionary ideas about the automotive industry. This post is the third installment in a series I hope to keep with over the next few months. In it I will try to empathize with different customer segments and think of new products or services that would serve them in fresh ways. If you think my ideas are legit, I’d appreciate your help in finding a sweet gig for the summer. If you think my ideas are far from legit, I’d appreciate your feedback.

---

One of the reasons I find the automotive industry very unique is because of how cars are sold. Think about it, how many products in the world have a named career path? In auto, you can be a car salesman, for almost any other product you're known just as a "salesman", except maybe for insurance. I think that's a testament to how special automobiles are in our culture and the uniqueness of automobiles as a product.

Because sales are so important to the industry, and because dealers don't seem to have changed radically in the past few decades, I figured I'd try to reimagine what dealerships might be in the future. Because dealers are a common link between many different types of customers, I'll provide a short description of every kind of dealer experience I can think of (at least in a first round of thinking). It would take much more market research to decide between this set of ideas.

Also, some motivation for this post: Apple has a unique retail experience for computers. If that's the case, it seems silly NOT to reimagine dealerships because the product (a car) is much more intricate than a computer and something people are as passionate about as Apple products.

Dealers as Auto Fan Clubs - for gearheads

There are some people who LOVE cars. These are the Top Gear-watching, horsepower-hoarding, car enthusiasts that see these products not as appliances but as works of art and human ingenuity. Why not interface with these people directly? I can see a dealership as being a community space for car lovers. Maybe you get a sneak peek at new models or features. Maybe you get to learn advanced auto-modding. Maybe you have a beer with other gearheads in your area. The dealership itself could be a place where people come together to share their love for automobiles. An added benefit to the OEM is that they can get valuable feedback from these super passionate, "extreme" users of their product.

Dealers as car support groups - for auto novices

Owning a car isn't easy. You have to maintain it, you have to understand how it works, and all this takes a lot of time. Why not have the dealership be an automobile concierge of sorts? Maybe if you have a dealer "membership", you pay the dealer a fixed fee (like a service package) and they take care of any repairs you need. You get an oil change and its free. They do basic maintenance on your car for you. They do all the taking care of the car, so the customer doesn't have to. Maybe they even teach you about how to take care of your car and give you opportunities to learn about car ownership. Think of it like getting an extended service contract or warranty for your vehicle and a car education to boot. The dealer would be a center of activity which helps people have a painless car ownership experience.

Dealers as urban convenience centers - for urban professionals

I used to work in the city and now I live in a smaller place. Something that was very annoying to me was always parking and doing minor repairs to my car - I could never find the time for something non-urgent. So, why not combine both these needs for urban consumers? The OEM would have a small parking lot, perhaps in a structure, and the driver would go to work...maybe by bus, subway, or bike share. While the driver is at work, maybe they can arrange to have basic car repair completed, maybe an oil change, new lights, a wash, tune up, tires, windshield wipers, etc. This would help with having a place to park, having repairs done, and having a hub to get people the "last mile" on their commute.

As far as this "last mile" stuff goes, I think that's a new business model in itself which I'll try to discuss in a future post as it is only peripherally relevant to dealerships.

Dealers as retail pop ups - for the spontaneous consumerist

You don't need much to sell a car. All you really need is, well, the car. So why not have a pop up on a busy street that has a small booth, but mostly just has models to test drive or inspect by passersby. That way it would keep "dealer" costs down and would still give potential buyers a chance check out cars as they walked by. This could be a fun and low-cost way for carmakers to give consumers exposure to their best products in an environment the consumer already is in...cities.

Dealers as classrooms - for the next generation of car owners, car dreamers, and car makers

Maybe car dealerships can be agents of social good, too. There are lots of kids that probably like learning physics, engineering, design, and similar things. With a curriculum built up for wide use, maybe car dealership could be an experiential learning environment for students across the country. After school students could go to the dealership and maybe a mechanic does a lesson with you. Maybe they bring in speakers who work in automotive engineering or design for sessions with parents and kids together. The dealership is a space that's not always 100% utilized that oozes engineering and design. Why not get other, younger people, interested as well?

Wrap up

Overall, I think dealers could go in many directions. But to do that, we'd have to think of dealers as more than "a place where cars are sold." I think we can, and should. As a bit of motivation / business case discussion - having an ongoing, positive, touchpoint with consumers is probably good for business. Once I leave the lot, I hate going to dealerships and mechanics. As a comparison, I love going to the Apple Store (or REI, for that matter) and kind of enjoy spending money there.

Show Me The Small Firms, Or, Why I No Longer Hate On Detroit Hipster Coffee Shops

I'll admit it, I've been a longtime critic of small-time Detroit entrepreneurs like the quintessential proprietor of a hipster coffee shop. These business owners, and those like them (e.g., food truckers, small-scale farmers, or yuppie-focused retailers), were people I often criticized because their businesses aren't disruptive. Those businesses probably won't "scale big" and they're not germinating from particularly novel ideas. I didn't think they'd really "move the needle" to make the city prosperous again, either. I actually still don't. But now, I'd like to eat my words - one micro idea that's actually executed is incalculably more valuable than a "big" idea that never makes it out of someone's notebook. Even if that micro idea is (another) **sigh** coffee shop.

For the past few months, I've read about or heard about many entrepreneurial success stories. Every big, global, value-creating company I've come across was started by a small group of people with a lot of discipline, passion, and luck. Apple didn't start off with hundreds of billions of dollars in shareholder value and neither did Starbucks. For that matter, neither did my mother's UPS Store franchise. All these business started with zero customers and dream. What they have in common is that someone actually did something to make these ideas into operating businesses. Once they were businesses in actual operation, it took a lot more work to make them profitable.

In Detroit, for a long time , I've been wishing for more people who had big ideas for companies or social enterprises. I even put a working group together to do some thinking about how to get people in Detroit to think bigger. The problem is that lots of people have big ideas (myself included) that they talk a lot about, but never do something about. Ideas that are never implemented never create any value - that's a fact*.

Let's go back to the hypothetical entrepreneur in Detroit starting a coffee shop. Say they produce one cup of coffee for one dollar and sell it for two dollars. That's one dollar of value that's created. That's one dollar more than a business with only the potential to create $1 billion (but that never gets started) will ever make. Potential doesn't pay the bills and doesn't pay wages either. What we need in Detroit is businesses that create value; so many businesses only ever amount to potential value. I no longer care if the business is a coffee shop or a software company. Profit is profit and new jobs are new jobs**.

Moreover, if all businesses started as super small companies, who knows what the small businesses in Detroit could become? Maybe someone who opens a food truck will become a farm-to-table mogul. Maybe a retailer with an innovative twist will grow their operation into the next nationwide urban department store. Who knows. The way I see it, we'll be a lot more likely to have a big hit if we have many hundreds of seemingly small new businesses instead of only having one idea with a high likelihood of making it big. We need small firms. Lots of 'em.

Of course, I'd love it if lots of people in Detroit were starting edgy, disruptive companies left and right. I really do believe that those sorts of businesses will create more value in the long run. But maybe if we have more successful entrepreneurs - of all stripes - those entrepreneurs will help teach other entrepreneurs - of all stripes - how to make it. If we play our cards right, and mentor those who are up-and-coming, maybe we could have an entrepreneurship multiplier effect in Detroit and those people starting food trucks will help a nascent tech company get of the ground later on. I sure hope so.

Sure, for a long time I thought it was a waste of time and money to start these businesses and celebrate them as if they were "saving" the city^. You might've called me an "entrepreneurship snob", and if you did you'd be right. But I've come around. Now, if a business is actually creating value in the real world it's okay in my book, even if it's a small scale company. We can worry about launching big ideas once we have a largess of small-time entrepreneurs already crushing it on the streets of Detroit.

For what its worth, I think we can (crush it).

---

*- For my business school friends: Strictly speaking, you can never create value (i.e., have a difference between willingness to pay and cost) if you never produce and sell a unit, right?

** - I'm assuming here that the profit and new jobs aren't coming at the cost of some intolerable, social externality.

^ - For what it's worth, the media acting like Detroit is back because we've opened a few retail storefronts is incredibly foolish and shouldn't be what Detroit aspires to be. Why? Frankly, because I don't think that will generate a tremendous amount of wealth in the long run. But the media's savior-making habit is beyond the scope of this post.

Creating From What You Know

Today, the Ross Net Impact club had it's fall kickoff event. At this event, Seth Godman the Tea-EO of Honest Tea gave a talk. It was fairly good, but one thing about the origins of Honest Tea struck me more than anything else. Seth just created it, somewhat randomly. The story goes, Seth had a business school class and his professor asked a provocative question while discussing a case about the beverage industry: "What's missing from the beverage aisle?" Seth said, a drink that was "just a tad" sweet. At the time, he didn't think to start a company. Years later, he was visiting a friend in New York, looking for a beverage in a cooler in Central Park. His friend was perplexed when Seth exclaimed that he couldn't find a suitable drink (there were sodas and presumably other beverages). But, he saw something else...he saw that a tea drink was missing.

So from there, he and his original professor created Honest Tea.

The obvious thing, (that never seemed so obvious to me before today) was that Seth had a unique insight that a tea-based beverage was missing, because he himself was a low-sweetness tea drinker. He knew the market space, it seemed, on an intuitive level. Not so much to confuse himself, but enough to see a missing product and create something. This seems to be the right way to create products, understand a market / customer need and think about simple ways to close the gap.

When I think about Silicon Valley culture (and what I hear about it) I think of people that are simply looking to start companies. They are looking for gaps so they can fill them, for filling's sake - not for any intuitive or intrinsic reason. This seems contrary to how businesses actually start. Rather, it seems like you understand something well and then you just start seeing the gaps. You create from what you know, and looking at what you know in a new way.

This seems to jive with innovation and creativity (in social impact contexts or otherwise): the best solutions come from front-line, tacit knowledge. So long as they can get out of people's heads, of course. The magic of creativity and innovation, it seems, is when someone is fortunate enough to get a deeply held insight out of their heads so that they can build something from it. What is important is making the tacit first explicit, then tangible.

---

Some friends and I were talking about this after the event. One friend pointed out that what I seem to know is people. Which is true, I have cultivated an instinct about how to bring people together over the past 20 years, since I was six years old. Now, I wonder, how do I look at people / relationships in a new way so that I can start seeing some gaps that could be filled by entrepreneurship?

Allying / Coming Out In the (Private Sector) Workplace

Friday is National Coming Out Day and I wanted to soapbox a bit on behalf of allies everywhere as a result. I also picked up a nifty bracelet from the Ross Out For Business Club after signing the "Ally Pledge". Thanks peeps. ---

I had a work experience where I thought I couldn't be myself and it was the most stressful time of my life, to date. I even wrote a business school essay about it. It was TERRIBLE. I was always stressed, becoming less healthy, and I wasn't performing at my best. I felt incredibly lonely and was losing hope that my situation would ever get better. I thought about quitting or taking a transfer, often. My situation wasn't even that extreme.

The more I talk to friends, classmates, and colleagues now, I find that everyone feels this way at some point or another. The chorus of people I talk to agree that it is a terrible feeling that is dehumanizing. Yes, dehumanizing.

If I felt that way for superficial reasons (e.g., I wasn't doing the sort of work I liked, my sense of humor wasn't accepted, people thought I was a goofball), I can't imagine what it would be life to feel compelled to hide your sexual identity or something equally personal. I'm guessing it'd be about a thousand times worse. As a result, I don't think we should ever let someone feel compelled to hide their sexual identity. It's hurtful and it's not fair.

I don't think those who identify as L, G, B, T, Q, or even an Ally should feel unsupported, either, because coming out can be such a hard process anyway. On the contrary, because it's so hard (and might subject the person coming out to emotional, career, or even physical harm) I think any ally needs to be an extremely, visible, and active one. A quiet ally might as well not be an ally.

We owe it to our friends, family, and colleagues to be supportive allies precisely because being out is really hard. And after spending some time in private sector organizations, it's broken my heart to see friends (who I deliberately call friends, they just happened to be colleagues) have to hide parts of who they were. I know the relief of being able to talk about my wonderful girlfriend with my friends from work or school (which you can't do if you're not out). It makes you feel good when a caring supervisor asks you about why you're smiling when they know you went on a first date the evening before (which you can't do if you're not out). All my older colleagues (without exception) loved talking about their kids and to take that away from someone is hurtful and a damn shame (afterall, baby pictures are adorable!).

More than that, if we're not supportive allies, our LGBTQ friends may suffer in their careers - maybe because they aren't chosen for a project, because their life circumstances aren't understood, or any number of other reasons. As allies, we can't let anyone feel like they have a reason to think that a colleague who happens not to be straight is any less talented or employable than anyone else. On the contrary, diverse perspectives (whether from sexual orientation, race, SES, educational background, career history, interests, location, anything) make business better. Speaking from a place of "profit maximization", teams can't afford not to have different flavors of people on them and have those differences be open, visible, and usable.

So today, while eating my peanut butter sandwich in an empty classroom I say to my friends, whatever flavor of human they are: I support you. For those who happen to L,G, B, T, Q or any type of sexual identity, I'm your ally. I'll try my best to be a good one.

--

PS - Special thanks to my friend Gabriel for reminding our class about the Ally Pledge!

Why we need legislative responsiveness (and dunk tanks)

So with this in mind, I'd like to propose some radical (read: wacky) alternatives which might actually make legislators "feel the pain" when they make decisions that are bad or "feel the love" when they make decisions that are good.

How to make legislators feel the pain and love One easy translation from the private sector is to have variable compensation or "pay-for-performance". In such a scheme you could have citizens judge legislators on a number of criteria indicating good performance. Then, you could have a bonus pool for legislators who do well and no bonuses for those who don't. This would be difficult because you'd have to design the incentives correctly, but it's possible. This isn't radical, however.

Campaign contributions aren't a great lever to use, but I think campaign spending could be. What if we limited campaign spending by legislators based on how pools of constituents viewed their performance? Say you had three pools of constituents, people in your district, people in your state, and a national group of non-partisan political elites. After every session of congress, each pool of constituents would be able to allocate points to whichever members they wanted. Then, based on those point allocations on a session-by-session basis, legislators would have different spending ceilings for their campaigns down the road. This would give an incentive for legislators to be responsive to constituents, immediately, beyond vocal minorities.

Another lever one could use to punish misbehaving legislators is to control access to the chamber floor or the media. In this scheme, legislators who get more done or better represent the country would have easier access to make remarks publicly. If a legislator was being wholly unproductive, they'd have their time to speak capped. You could perhaps evaluate this based on a constituent voting scheme or by legislators policing themselves.

Finally, here's a funny one that might actually work. Below I discuss why shaming might not be good enough. But, if we're going to shame legislators let's REALLY shame legislators. Let's do a gong show. In this scheme, maybe we put a big dunk tank on the Capitol steps. Let's put a legislator above that aforementioned dunk tank. Then, we have a game show on a regular basis where a legislator gets grilled by a moderator. Then, people on social media vote as to whether that legislator should get dunked or not. If they get off the tank without a dunking, we'd make a big deal about it to really make them feel good about it. If they get dunked, we'd make them wear a "dunked" cap until the next dunking show. They'd look really, really foolish if they were dunked. We'd do say, 10 or 20 legislators during each show so that over the course of a term everyone would have to face the dunk tank.

Anyway, some of these are crazy, some are hard, and others are simple. Overall, though, I think there's many better ways to have immediate responsiveness of government. Surely, all these ideas are not ready for implementation. I merely want to provide a vision of alternatives that we might use. If there's big demand, I'll flesh one of them out. If not, I hope they help the readers of this post realize that responsiveness in government is difficult, but very important.

Extended Discussion on Voting and Campaign Contributions (and why they don't work): The two mechanisms we seem to have are voting and campaign contributions. Unfortunately, though, these happen every two, four, or six years which diffuses the effectiveness of those feedback mechanisms - if you vote for a congressperson every two years, they'll have no idea what the basis of your decision is. It could be because of the government shutdown or because you like their views on pet adoption. A vote isn't a great feedback mechanism if a legislator doesn't know why you vote and you vote very infrequently.

You could also communicate your viewpoint after an event by making campaign contributions for a particular candidate. But that runs into the same problems of diffusion above: no legislator can really know exactly why you contribute to them. They probably shouldn't anyway, because if you contribute for a specific purpose the legislator is running into a gray moral area (potential bribery).

Moreover, both these mechanisms don't actually impose a direct cost on a legislator...by not giving a vote or a contribution, you're simply withholding a future benefit. Legislators don't "feel the pain", so to speak. Also, I don't think shaming - for example through letter writing or social media - does enough because it's also diffused. On average, any legislator will probably get lots of different written feedback from constituents but they plusses will probably cancel out the minuses. Moreover, constituent letters and tweets are very easy to ignore, especially when media channels are already saturated with information.

Irrational Manager / Market Share Fallacy

- Increased Market Share = More Programs

- More Profits = More Impact

More programs doesn't mean more impact, just as more market share doesn't mean more profits. Not-so-good Managers in both sectors don't understand this fully. Increasing market share or programs makes you look like a better manager / executive, but it doesn't mean you are a better manager / executive.

The anecdotal difference, I think, is that founders in the private sector are crazy about profits whereas founders in the social sector seem more likely to be interested in their "market share" than their private sector peers.

Future of Auto #2 - Imagining Data (not tailpipe) Exhaust

This post is the second installment in a series I hope to keep with over the next few months. In it I will try to empathize with different customer segments and think of new products or services that would serve them in fresh ways. If you think my ideas are legit, I'd appreciate your help in finding a sweet gig for the summer. If you think my ideas are far from legit, I'd appreciate your feedback.

Note: I'm getting really excited about Auto. It seems like there are lots of ways to innovate this industry. It's wide open. The key seems to be to focus everything other than the car itself.

---

Update: As it happens, some friends who are more intimately involved with auto let me know that the transmitter portion of this idea already exists, but that the analytics is still underdeveloped. Though it makes this post a little less valuable, it probably makes the potential for a business a little bit more possible. Maybe one could collect more sophisticated data if necessary but then emphasize the analytics component.

My friend Cameron put it well, "The ability to capture data has far outpaced the ability to do useful stuff with the data."

---

Original Post: Tonight, I'm trying to get inside the head of people who manage fleets. Those people don't drive cars, their drivers drive cars. But, can an auto company provide them added value? I think so.

As I understand it, fleet managers probably want to know two things, mainly: how much their vehicles are being utilized and whether the cars need maintenance. Given this insight, it seems like there's lots of data that could be captured to help address those needs, with little inconvenience to the fleet manager or the driver.

Imagine this: an OEM installs a transmitter on every one of their fleet vehicles. This would tap into data about:

- The vehicle's condition: e.g., it's oil level, fuel level, engine wear, or any data that is already produced by the car or could be cheaply captured with an add-on sensor

- The vehicle's location: i.e., with GPS

- The vehicle's use: e.g., RPMs, acceleration, g-forces of turns

- Anyone interacting with the car: e.g., a driver driving the car, a mechanic

Future of Auto #1 - The Shareable Car

This post is the first installment in a series I hope to keep with over the next few months. In it I will try to empathize with different customer segments and think of new products or services that would serve them in fresh ways. If you think my ideas are legit, I'd appreciate your help in finding a sweet gig for the summer. If you think my ideas are far from legit, I'd appreciate your feedback.

----

Speaking as a Millennial, It's not that I don't like cars. I actually really like cars. I grew up around cars. When I played with Legos as a kid, I used to make them into cars (full disclosure: and spaceships that doubled as cars). I think the technological innovations in cars are astounding and that the invention that's currently happening with in-car tech is fascinating.

The thing is, I wish I had a lifestyle that didn't require a car. See, I want to live in a city and walk places. But I still want to be able to use a car. And, I still want to own a car. I want some of the private benefits of having a car while still sharing the fixed costs of having a car with other people.

So, why not have some of the benefits of both with a shareable car? What if people who aren't necessarily family or members of the same household could own a car together, too? Maybe the beginnings of an idea could work like this:

OEMs would create leasing schemes in which the leasees can be of any association to each other. Maybe they're neighbors. Maybe they're friends. Maybe they're roommates. Maybe they just met and live down the street from each other. Under the agreement they would each pay for insurance and maintenance through the OEM and sign their lease together. They'd both have access to the car. And, it wouldn't be a generic car like Zipcars. It'd be one they picked all together.

A supporting technology for this idea would be a mobile app which helps the co-leasees share the car. The app would track mileage and usage so that the friends could split gas and maintenance (i.e. variable costs) quickly and automatically. This app could also be used by the friends to reserve use of the car at the times they need it, or maybe coordinate how they can carpool. Finally, the app could contain a unique identifying mechanism which allows the car to adjust itself to the driver's preferences, whether it's music, recently navigated destinations, temperature, or seating arrangements.

Of course, there are problems with this idea (e.g., who would want partial ownership of a car with a friend, especially if that person doesn't live within parking distance of your residence). I don't attempt to resolve all the problems here. I merely intend to lay out the beginnings of what could be a good discussion about the future of the auto industry and a potential product or service offering.

Business Must Do Good

The Metaphor To have a healthy body, one must eat a variety of foods, at least in the long run. Let's say you grow your own food and you need fruits, vegetables, grains, and proteins to be healthy. Say you run out of fruits in your refrigerator, and you're hungry and the store is closed. So you eat vegetables, grains, and proteins. Say you don't eat fruits for a week. You'll still probably be okay, though you like fruits. You just go about your activities and you have lots of grains and proteins. You don't worry...you just keep eating.But say it's been several weeks. Now, unfortunately, you're starting to feel weary. You really need the nutritional value of the fruits. You start to catch more colds and generally feel malaise when walking around. But uh oh, now you're out of vegetables too. This only makes things worse and you start to feel worse whenever you get sick. Thankfully, grain is still cheap and easy to grow. Your ability to eat meat, however, is fading because you're less and less able to work hard in your garden to grow the things required to support livestock. In fact, your family tells you to stop raising and eating meat…saying you should focus on growing and eating grain.

The problem is, your body is less and less resilient the more you eat only grain. There's no telling how you'll react when you get sick. You'll probably respond very badly to ailments and will probably have to go to the hospital. Unfortunately, the hospital is expensive and it will take you a long time to pay off the bills…especially if you go back to a diet of grains after you're released.

The Metaphor, Explained This is a metaphor for how I think society works. We consume a lot of different types of value: economic, social, civic, and spiritual (grain, vegetables, meats, and fruits, respectively). And we can subsist on one type of value, perhaps, for a long time. The consequence is that it makes our society - the living organism that it is - weak and more unable to respond to shocks.

Economic value, much like grain, is easy to grow in a variety of climates and is reasonably consistent across the globe. It provides energy. It's satisfying and makes you feel temporarily at ease. It's easy to measure and store. It doesn't spoil quickly. It fills you up.

Civic, social, and spiritual value are much like vegetables, fruits, and meats. Everyone has different preferences with those kinds of value. They are harder to classify and they decompose much more quickly. It takes getting used to them to like them. They don't always fill you up as quickly as grain, so they seem less important to eat.

But these types of value are needed, much like in the example of the farmer, to have a healthy society. We need a mix of value being created to be able to prosper, I think. To put it into the nomenclature of a 4 year old and his parents…we need to eat our vegetables, which is to say that we need to create value beyond that which is economic to have a healthy society.

Note that there's a difference between the vehicle creating value (e.g., business, government, non-profits, hybrid organizations, informal organizations, etc.) and the value that those vehicles create. For example all these types of organizations creative a mix of value (e.g., non-profits create economic, social, and civic value…as do the rest of the value creating vehicles I've mentioned). I'm concerned with the value that's created and consumed, regardless of the vehicle that creates it.

The Argument For Why Business Must Do Good I'd contend that business is the vehicle that creates the largest amount of value in society (not necessarily the most important value…just the most). Think about how the largest companies have more assets and people associated with them than some nation states. They also make the resources of non-profits look like pennies on the dollar. This is especially true because government has become weaker in the past several decades, in no small part because of the influence of business interests.

I'd also contend that the majority of the value that businesses create - especially in this unfortunate era of shareholder capitalism - is economic value. When it comes to civic, social, and spiritual value, businesses might even consume more than they replenish.Because they are the greatest force in creating value of all kinds, and they are severely skewed in the type of value that they create, I'd contend that businesses must do good. Let me even reframe this notion…I contend that businesses must create economic value, but at very least also leave behind more civic, social, and spiritual value than they consume. If their net value creation leaves our stocks of value (e.g., the total amount of social, economic, civic, and spiritual value) lopsided, our society will be unhealthy.

They way I see it, in the long run if business does NOT do good, our society will collapse. Which is to say that if their net value creation doesn't preserve the balance and growth of civic, social, spiritual, and economic value, our society will collapse. As a result, I'd contend that business must do good.

The Corollary I don't think the other value creating vehicles that exist (government, non-profits, churches, etc.) are off they hook. They ought to help in striking the balance of value that's needed. I don't implicate them here because they're proportion of value creation is smaller and they're more conscious of the balance they need to strike (in my humble opinion) than is business.

I strongly believe, also, that we are all much better off when these stocks of value are in balance because they create synergies when they interact together. In other words, when these stocks of value are in appropriate proportion, our total amount of value grows bigger and faster than it would if our stocks of value were lopsided.

Can business do good?

It perhaps was a foul to talk about that in statistics. But, shouldn't politics and morality be exactly what we should be talking about in a business school classroom? Aren't the effects of business on society and morality strong enough to prevent an outright aversion to political discourse?

I'm not asking for business school to be a public policy classroom. But I am appalled with the seemingly unending focus on profit maximization and the creation of economic value. Without being willing to teach that there are reasons to tame shareholders' interests, I don't know how we can expect that business will do good for society unless it happens to be convenient. The way business schools seem to be now make me think socially responsible business might actually be a gimmick.

Maybe I was expecting too much to have my moral positions challenged and refined in the classroom. Maybe it will still happen. But until then, a question lingers on my heart and mind:

Is business that truly does good even possible?

Cola meets the maker movement?

Background

Basically (and I'm being really basic) the CSD industry operates on a franchised bottling model. What we consider to be the company, let's just go with Coke, makes syrup which it then sells to bottlers. This "mothership" company also puts in a lot of marketing effort and deals with big national contracts. The bottlers add in carbonated water to the syrup sold by the mothership to make a finished product. The bottlers then sell and distribute the bottles within the territory they have exclusive rights for.

There's a lot of nuance, but this is basically it. There are a few other interesting facts about the CSD companies:

- Recently (in the past few years / decades) Coke and Pepsi have been buying up bottlers, but operating them as separate companies

- The companies have been expanding into emerging markets

- US beverage consumption per person (all beverages) has been flat for the past forty years...it's about 185 gallons per person, per year

- Bottlers have high operating costs and relatively low margins

- Retail consolidation has given larger retailers a lot of leverage when negotiating prices with bottlers / mothership companies

- CSDs have been trying to expand into non-CSD beverage (e.g., bottled water, juices, sports drinks

- Cut costs by eliminating a few steps in the value chain and punting those costs to consumers themselves

- Providing a value-add to consumers (coke whenever you want it!)

- Provide consumers the opportunity to customize their product experience (maybe you have a cartridge for three types of soda and two types of sweetener)

- Provide a direct-to-customer product, which probably has a better way of linking marketing and promotion to consumers, so you can probably develop a better relationship with those customers for upsell opportunities for product bundling (which becomes really useful as you diversity product mix beyond beverages or even just beyond CSDs)

- Maybe you could even create retail locations and turn the product into a lifestyle brand with accessories and add-on opportunities for enterprising soda enthusiasts

Organizations' Dirty Trick

The organizational world doesn't have to be this way. We could be more purpose-driven, or have more freedom at work. We could easily have more equality in pay. We could be doing things that matter, instead of wasting away in bureaucracies which are wholly meaningless. Why is that we don't accept oppression in public life, but accept it from our bosses?

Reframing the question is essential, meaning, allowing ourselves to view organizations fundamentally differently is essential. I will figure out how. Or more likely though, we will figure out how.

Let's map the social sector's genetic code

The Loneliest Detroiter

Why I want to provide seed money for parties

- I'd give the host $50 in cash to use however they wanted, the host would be expected to spend $25 of their own (or more if they want) to get to the $75 threshold - By keeping the party small it brings more attention to the people rather than the party. And, hosts have to be invested...thus not giving them enough money to cover the whole cost of the party.

- Hosts would invite guests of their choosing:

- Each guest would be allowed to bring 0-2 friends - This keeps the party manageably sized, and by bringing friends it commits people to come...other people are depending on you to be there. Also, third degree connections (the friend of your friend's friend) is where networks really open up because you're not likely to know that person, but there's probably enough trust between you and that person because you have some ties but not a strong enough tie to make you scared to break things off if it's awkward. Third-degree connections also are where the number of contacts you have exponentially increase.

- At least one of the friends each guest brings can't already know the host - This is to promote new people meeting each other - This helps ensure diversity, but also ensures that the group isn't a bunch of strangers. This is ideal...there's enough trust for people to feel comfortable, but enough diversity to meet new people.

- Guests would be encouraged (but not expected) to bring something to contribute to the party - a dish to pass, decorations, beverages, etc. - Guests have to be invested. But, people also feel good when they exceed expectations...hence the soft request for contributions. Also by contributing, it's implicitly implied that you can participate in what's happening.

- Hosts would pick some small activity to help get a conversation going. - Something like helps convey a purpose for being there. The guests get a signal from the host that their presence matters and that their contribution / thoughts are wanted. A little structure gives people permission to participate and think about what they want to say / share beforehand. It's also not stifling when you have something simple to get conversation going.

- We'd share the experiences online - Open accessibility is good. tumblr's / blogs are easily shareable. Lots of people being able to learn from a few people is cheap and valuable. And, it makes it feel like something was produced.

The danger of "all in one place"

As it normally goes, at least when talking about organizations and management or creative spaces, people imply that having things - whether it be people, business process experts, information or materials - co-located...all in one place is what is needed, that having these things all in one place is obviously good and useful. Having things all in one place reduces transaction costs because the task of combining goods or services before consuming them becomes cheaper. This makes sense.

Except when it doesn't. For much of the 20th Century, perhaps it was desirable to have things all in one place. But now whether it's goods or ideas, it's a lot easier to instantly bring things together from disparate places in the moment you need them. Take Amazon for example, they can get you goods from around the world at a few days notice, maybe less than that. This makes it less necessary to have a superstore within 5-10 miles of where you live. Shipping things is cheap and fast, world-wide so it's not necessary to have things all in one place.

This is even more true for digital consumables, like information. It costs virtually nothing (pun intended) to scour for and synthesize information from across the net, as long as the information is connected. We don't need to have massive libraries or other repositories of concentrated information as long as that information is digitized, consistently formatted, and searchable. To spend effort putting information "all in one place" to just sit around is almost laughable because of how easy it is to bring information together within seconds.

The same thing goes for organizations. Organizations don't need to have all materials and expertise in-house, anymore. They can combine things and form teams around problems within hours if necessary, bringing disparate skill-sets and passionate people to a problem from around the globe. Fewer and fewer organizations need to be "one stop shops" or "all under one roof" to be successful. The same forces that have made it easy and cheap to bring goods and information together instantaneously apply to people, too.

More than merely pointing out that having things "all in one place" is inconsequential, I'd say an "all in one place" mentality is actually dangerous. Having things all in one place requires a lot of effort and a lot of internal structure. To make having something "all in one place" worth the effort you have to spread out the fixed costs of doing and make processes efficient when in operation. This often requires rigorous, inflexible processes which stifle creativity and promote the territorialization of people and resources. In other words, having things "all in one place" requires standardization, and standardization stifles creativity. That's a bad thing if you're trying to do something creative.

Now, throw my point of view out the window if the example in your mind doesn't require creativity. The rub is, there are fewer and fewer circumstance where that's actually the case, at least in the organizational world. Being efficient isn't always a useful objective anymore; the need to be creative often trumps efficiency.

So, I'd ask, before you make a statement implying that having things all in one place is unquestionably good, make sure that's actually what you mean, and that it is truly beneficial to have things all in one place.