The Market and the Middle Class

With regard to the changing winds of the American middle class, I don't know how we got here (I'm not an economist) or how to get us out of it. What I do understand is how "the market" of businesses creating goods and services will respond. It's not pretty, and the writing is already on the wall. My prediction: businesses will chase dollars and more new products and services will serve the upper classes, especially as the size of the middle class shrinks. This will accelerate income inequality as the lower and middle classes have less access to the products and services that they need to maintain or increase their income and productivity.

Here's an example of what I mean. Imagine all the new products and services launched in recent years. Since apps are a very visible product for readers of this blog, let's use those as an example. I will make two points, first that entire categories of products are less accessible to the middle class and second that the selection of products in categories accessible to the middle class will wane.

The mobile app market is booming, with revenues that will reach $25 billion this year. The point of category accessibility is a simple one. Unless you can afford mobile devices and data, you can't afford apps. So, if you are not wealthy enough to have a smartphone / tablet / etc. you can't take part in a new and very important echelon of the economy. If you can't pay up front, you can't play.

I don't think this is unique to apps, this problem exists in pharmaceuticals, cleantech, or any innovative industry. If you don't have a certain level of wealth / income to pay the up-front cost of entry to use a new product or service, you can't even begin to reap the benefits of that new and emerging industry.

Another problem is that the middle class shrinks, less and less versions of a product will be made for them. In apps, what this means is that fewer and fewer quality apps will be at an affordable price for middle class buyers. If you were a businesses wouldn't you cater your product (and your prices) to customers who could pay more, especially if the amount of middle class people you could potentially sell too was shrinking? In the app world, I think this will mean more and more apps worth downloading will need higher and higher levels of payment.

In the app world, this may seem trivial (even though I'd contend it's not because apps can increase productivity and therefore affect learning and income). But extend this effect across the economy to clothes, consumable goods, cars, education, healthcare, and others. In aggregate, middle class people will have less and less products they can use to be more productive, educated, or otherwise attractive as employees, putting them at a disadvantage for maintaining or increasing their income. The wealthy will have more and more products developed for them which will allow them to be healthier, happier, and more productive - begetting them more wealth.

But wait, another reason the market effect of product and service selection will perpetuate inequality is because of cultural distance. As income inequality increases, those developing products (who are presumably wealthy and educated, especially in innovation industries) will have less contact with those of lower classes. This means they'll have less awareness of the product needs (and potential business opportunities) of the lower classes. Because you can't make a product without knowing what the customer's need is, the lower and middle classes will have less products made for them which make their life better.

The writing of this happening is already on the wall. Think of all the new businesses you've seen get big in the past few years (either from friends, the news, or even kickstarter). How many of those products could a lower or middle class person afford? How many of those products were even catered to the needs of a lower or middle class person? Most of the new stuff I've heard about definitely does NOT cater to a lower or middle class person. (I'm not giving examples, because I don't want to be mean to friends who are launching businesses. I support them wholeheartedly).

I'm a big proponent of entrepreneurship, so I'm not trying to trash entrepreneurs who don't serve the lower or middle class. And, all of what I'm saying is fair and legal by the law of our land.

What I am pointing out is one, often unrecognized, way that the market will perpetuate and increase income inequality if left to its own devices. I point it out because it doesn't sit well with me. Because it doesn't seem right. Because it doesn't leave our world in a better place then we found it, it seems like it leads to a world with more suffering.

I also point this out because income inequality shouldn't just be a concern of "poor people" anymore. It's a very real issue for many more Americans these days and in ways they may have never considered, such as the products and services that are even available to them. As a child of a middle class family, I never thought that income inequality would be such an applicable issue to me. And now it does.

---

Another interesting tidbit about the middle class from The Brookings Institution. Also, here's a decent summary. Has anyone heard of a study examining how levels of inequality affect the types of products and services that launch? I can't find one.

The Foundation of Innovation Is Empathy

How innovators approach their work is a choice, and this choice boils down to how you prioritize two things: serving customers and making money. Surely, every successful innovator has to balance these two priorities, but sometimes these two priorities conflict, especially in day-to-day operations. Every entrepreneur, every non-profit, every company, every organization, every innovator has some version of this tradeoff. At the end of the day either your customers or making money take priority. When these interests conflict, which will you choose over the other?

For companies that want to innovate, I think they have to prioritize serving customers over making money because innovation is fruitless without the identification of a real, clear, customer need (which you can't find out if you don't prioritize it). In all the innovation work I've done, it's very easy to delude yourself into trying to force a solution on customers which they don't need because it's more profitable.

Choosing to prioritize customers over profits is a huge commitment to make, though. What I find interesting is why anyone would choose to prioritize their customers' needs over making money. I think what's at the core of it is empathy because empathy gives you reasons to forego short-term profits for long-term value creation.

It's easy to commit to serving someone if you feel for them and understand what they need. It's easy if you care about their experiences and what happens to them in life. It's easy if you value and respect them and constantly put yourself in their shoes. Committing to serving someone - like a customer - is really, really hard to stick with if you don't empathize with them.

Again, I'm not suggesting that businesses should ignore the need to make money, in fact they must do quite the opposite. But I am suggesting that innovation requires prioritizing your customers' needs over profits and going to the mat for them sometimes. And that critical ingredient for innovation - commitment to serving your customers' needs - requires empathy. Empathy is a foundational attribute, I think, for individual innovators and innovative companies.

Innovation cannot exist without empathy. And, I'd say that these days innovation is pretty important.

So, the real quandary is, if innovation is important and innovation requires empathy - how do you develop empathy for customers within companies who believe the shareholder value thesis?

Serving The Long Tail

If you're working for a company, chances are that your company falls into one of two categories: Business-to-Business (B2B) or Business-to-Consumer (B2C). In the past, the way this normally has worked is similar to the auto industry. The Original Equipment Manufacturers (OEMs) - think GM, Ford, and Toyota - are the B2C companies selling their product to end consumers. These companies do the final assembly of the car and build consumer brands. The OEMs are supplied by several tiers of B2B companies - businesses that serve other businesses.

Generally speaking, Tier 1 suppliers are big and the companies who supply the Tier 1 suppliers (these are called "Tier 2" suppliers) are smaller than Tier 1 suppliers. Tier 2 companies are supplied by Tier 3 suppliers who are even smaller then them. You can think of it this way: the OEMs are the biggest fish and they use stuff supplied by smaller fish, who are supplied by smaller fish, and so on. That's just the way it was back then.

In today's sort of world, it's hard to go out on your own (and say, be an independent car maker) because when you're a big fish you have the benefits of scale. When you're a little guy you have to do all your own hiring, all your own sourcing, all your own marketing, and so on. In a nutshell, when you're a little fish, it's hard to compete because you can't spread fixed costs out across a big, big business.

This is all changing, now, though. It's becoming easier and easier to make it as a "little fish", if you're in an industry with a long tail.

Serving the Long Tail

There are lots of industries that have a handful of big companies and thousands of small players. In this sort of industry, the thousands of little players are called the "long tail." As I've mentioned above, the companies in the long tail don't have the benefit of scale to spread out fixed costs. In theory, someone could make a ton of money by providing a service to all the little fish in a long tail industry. This opportunity has existed for centuries.

This is hard however, because it's not trivial and is often expensive to serve thousands of customers simultaneously if you're a small company. Coordination costs make it difficult to serve the long tail.

But all that is changing. Digital technology is making it possible to dramatically cut coordination costs. Thus, it is now more possible than ever to serve the long tail. Lots of companies are now serving the long tail, here are a few examples:

Kickstarter - The market for creative goods (e.g., video games, movies, gadgets, etc.) are often dominated by big players. One obstacle to being an independent player in the creative goods market is the difficulty of finding funds and the difficulty of attracting a customer base. Kickstarter helps independent people making creative products do both.

Amazon Web Services - If you're a software developer, you need server space and computing power to run an app. This stuff, historically, was only accessible to big companies with deep pockets. Now, Amazon Web Services and other cloud storage and cloud computing providers make it affordable for independent developers and small software companies to get their prototypes off the ground.

Elance - Large companies gobble up talent and do many things in-house. It was hard to be a freelancer (whether it be in writing, publishing, marketing, consulting, etc.) because you couldn't find clients. Now, Elance is one of the many services that allows talented professionals to find clients, and avoid selling out to big firms (or even small ones). At the same time, small companies now have unprecedented access to skilled professionals, often for short-term jobs.

Castle - There are a few big property management companies. But most landlords aren't big, and there are LOTS of small property managers who own and manage real estate. The cool dudes at Castle are working on a product to serve these folks. Oh, and, even more awesome...they're Detroiters!

The Opportunity Of Serving The Long Tail

For a long time independent companies / freelancers have been woefully underserved, because the costs of serving can't sustain profitability. But now, because of digital technology, it's suddenly becoming possible. If you're a clever entrepreneur, one way to be very successful (and feel great because you get to serve an underserved market) is to do the following. I'm focusing on B2B companies in this post. But, the same logic could be applied to B2C companies. Also, if you're interested in serving underserved companies through business, check out the Base of the Pyramid Strategies work being done at the Ross School of Business. (I'm taking a class on this next term, I'm stoked).

Anyway, follow these steps:

- Find a market that has a few large players (because this indicates that there's money to be made there) but that is also highly fragmented by loads of small or independent players.

- Understand the needs of the independent players. How are they being underserved?

- Of the needs you've identified, pick one that can be addressed with a solution that mitigates coordination or other transaction costs. This is likely a cost that larger players can afford to do in-house and is solvable using digital technology*

- Build the product / service

- Take it to market

If you start thinking about it, you'll likely think of many, many, industries which have a long tail AND which have a long tail that can be served via digital technology. Let me know if you make it big.

* - If you're looking at a solution (like Kickstarter or Elance) you have to consider the needs of anyone interacting with the independent players. In the case of Kickstarter, for example, you can't just make sure the people making the creative projects are having their needs met, you also have to incorporate the needs of the crowd funders when building the solution.

Has anyone really thought about what Detroit needs?

One way to simplify business school, is to know that to succeed in business you have to do this. Seriously, this is all you've gotta do:

- Define who your customer is.

- Find out what they need.

- Imagine something that will fill your customer's need.

- Make it.

- Give it to them.

That's it, that's all you've gotta do. Of course, there's a lot of sophistication with how to make this happen.

The beauty of this 5 step process is that it's broadly applicable. You could apply it to lots of different organizations across sectors, whether it is a foundation, a family, a government, a neighborhood, a non-profit...anything. What I can't fathom is what Detroit needs. I have my own opinion on what Detroit needs, but I can't find anyone articulating it clearly across the city. In my observation, everyone is prescribing solutions and not understanding real needs. Here's what I mean:

Breaking it down for Detroit to succeed

- Define who your customer is. - This is easy, sort of, let's assume citizens of the City of Detroit.

- Find out what they need. - This is what I don't see being articulated. Do people need agency? Do they need to feel safe? Do they need distraction and entertainment? Do they need opportunity? What does Detroit need, really?

- Imagine something that will fill your customer's need. - Street Lights, No Blight, Public Transportation, Good Schools (notice that these are solutions, not descriptions of need.)

- Make it. - Self explanatory.

- Give it to them. - Self explanatory.

Here's why it matters. For every need that exists, there's hundreds of ways to solve that need. Take "bring light to darkness in your home" as an example of a need. You could solve that need with a fire, a lantern, a fluorescent light, an incandescent light, a flashlight, etc. People don't need lamps, they need light in dark places. There's a difference.

The problem is, when you don't define what someone needs really well, it's hard to give them a solution that really works for them. Providing solutions to problems is aided greatly by defining the right need. Solutions without real needs don't last and aren't useful.

So for real, if anyone has found good articulations of what Detroit needs (or what subgroups of Detroiters need) please point me to it. If nobody has found anything, we're in a bad spot because it means people are prescribing solutions without understanding needs. That leads to bad solutions or solutions that work only because of luck.

Two Higher-Ed Fallacies (which are near to my heart)

Let me break down two fallacies I see in higher education: The MBA Recruiting Myth Here's how the story goes. One thing to know about MBAs is that we obsess over finding a job.

Right now, the cost of higher education - an MBA is not excluded from this - is appalling. I will have close to $150k in debt by the time I graduate from the Ross School of Business, for example. This creates intense pressure to find a job, because if you don't have a job you can't pay off your massive amount of debt. Moreover, this amount of debt makes it difficult for anyone that doesn't have at least some cash saved up (which normally is the case for people who already have high-paying jobs or have a well-to-do family) from taking the risk of applying to business school - which by the way is costly...over $200 per application plus the cost of interview travel and GMAT prep.

Even worse, because of all the debt, most people are pressured to take low-risk, high-paying corporate jobs. A lot of folks I know don't see themselves making a career where they get a job out of school, because they don't want to work for a corporation or have higher aspirations, etc. The debt, however, handcuffs your to work for a larger company with a lot of prestige for awhile unless you're extremely risk tolerant and can fend off the social proof of your classmates who opt to work for Fortune 500 companies or prestigious professional services firms.

The people who benefit from the high tuition rates are the business schools (who are now justified in raising prices higher) and large corporations (who now have a captive pool of talent to pluck from that has less freedom of choice because of their debt).

Here's the fallacy though. What business schools do is bolster efforts to help students find high-paying corporate jobs. What would be a more elegant solution (which is difficult, of course) is to lower the cost of attending business school. This would allow people more freedom and bring in a more diverse group of people into business school anyway.

The Cut-and-Run From Liberal Arts Myth This one is more simple.

Lots of liberal arts majors (apparently) are having trouble finding jobs. The logic goes, that liberal arts majors don't have the same skills as their peers coming out of professional backgrounds (like business and engineering). As a result, the pundits say, we should have less funding go toward liberal arts programs and should instead funnel students toward STEM educations.

Let me first counter the notion that liberal arts students are less skilled than their professionally-oriented peers. It's false.

In my own experience I consistently find that liberal arts majors are more imaginative and are better communicators. They think more critically and better understand ambiguity (and customer needs). It's not that liberal arts majors have less skills they have different skills which are less tailored to entry level jobs. The skills that liberal arts majors have serve them well when they are leading organizations, not starting out in them.

Here's the fallacy. If liberal arts majors have valuable skills, we should not push people away from the liberal arts. Rather, we should help them build the brick-and-mortar skills (MS Excel, basic business writing, meeting management etc.) that their business and engineering counterparts have. This could be done through classroom training, co-curricular activities, career-prep training, or internship support.

I'm proud to say that my alma mater, the College of Literature, Science, and the Arts at the University of Michigan is following this path of helping liberal artists bolster their professional skills. The school realizes both that the liberal arts are valuable AND that liberal arts majors need to supplement their skillsets. The school is working to do so in a number of ways. The method I support regularly is the LSA Fund for Student Internships, check it out.

The Point Often, institutions solving problems make interesting choices when choosing solutions. In this case, I think conventional practices are rooted in counterintuitive conclusions. Instead of helping cash-strapped MBAs find corporate jobs easier and pushing liberal artists to other fields, why don't we lower the cost of getting an MBA and implement programs which help liberal arts majors develop the so-called "practical" skills they are missing.

Those seem like much more sensible solutions that have higher long-term payoffs.

The Fallacy of Building Social Capital Efficiently

This thought should have probably occurred to me many months ago, but it did not. I was hanging out with two of my friends (and fellow Ross classmates) Ina and Janelle this past Friday. We did, roughly, the quintessential day one does with people who haven't really spent time in Detroit. First we brunched at Hudson Cafe, then went for a walk on the Riverfront via Downtown, toured the Detroit Institute of Arts, and wrapped up with cocktails at the Ghost Bar.

It was a lovely day.

Later that evening, I was able to grab dinner with another friend, Wayne, and we stumbled upon the topic of what it takes to build efficacy and strong relationships to the city and across the city.

We agreed that there's some role for formal institutions and programs: like panels put on by the Gilbert family of companies or tour groups.

But I realized that the real, enduring experiences are not the mass-produced, highly efficient, forays into the community sponsored by anything ranging from a corporate conglomerate to a tech incubator. No, what really builds Detroit loyalists is when newcomers are introduced to the city, personally.

That's how I was indoctrinated, and every "success story" I've ever seen of people engaging with Detroit has been the same. It takes a personal touch and more than an hour-long panel discussion or walking tour.

This is a lesson, I think, that applies more broadly when building social capital of any sort. Efficient, "at-scale" programs may be perceived as being cost-effective or "more bang" for our collective buck, but the TLC of an intimate introduction to a community is what lasts.

And that's what I think we need in our city, connections that last - between people and the city itself and interpersonally between people across the city's niche communities.

Of course, this sort of approach is hard to make a business case for because things that are time-consuming are also expensive. This sort of approach also precludes the organizer of a scalable connection-building program, from becoming a rainmaker that holds power because of his / her place as the gatekeeper in the center of the network. Power comes from holding the keys to the castle and being the person that makes an introduction.

When building social capital, however, aren't lasting relationships that take a lot of work more important than shallower relationships that are manufactured efficiently?

How Cultures Form, Part II - Forming Culture In Detroit

A friend and colleague who I've never had the privilege to meet in person, framed up my last post on how cultures form very clearly in a tweet. I'd to like to use his simple framing as the foundation of evaluating how culture forms in Detroit and thinking of solutions:

.@ntambe on how cultures form. The ideas (& actions) that get reinforced the most become part of the culture. http://t.co/TpUe26TuH6

— Matt Frost (@mattgfrost) March 5, 2014

I agree, the ideas (and actions) that are the most reinforced become part of the culture. If that's true, there is a two step process for evaluating and improving cultural formation in Detroit, via two questions.

- Do cultural ideas and actions becomes reinforced (or not reinforced) effectively?

- If answering no to the first question, what should we do about it?

I'll now consider these questions in turn. In my last post, I broke down cultural formation into two categories with three components each. I'll use this framework as the basis of analysis:

- Culture forming behaviors must be present and effective:

- The interaction channels which enable culture forming behaviors must be present and effective:

Do cultural ideas and actions become reinforced (or not reinforced) effectively in Detroit? First, a look at culture forming behaviors:

Expressing cultural ideas in Detroit Something I find interesting about the people who express cultural ideas with their thoughts and actions in Detroit is that attention is focused on a limited number of voices and stories. Individuals and media alike reinforce the same class of social entrepreneurs, the same foundations, and the same business leaders. As a result, I think the only people who express ideas about the culture are in the same group of people. Everyday Detroiters don't have a means of asserting their spin on what Detroit means to them, and probably don't feel like it's valued.

We certainly have a strong, clear, and confident group of people expressing cultural ideas in Detroit, the group just isn't very diverse. The poster children of the city are the ones that are vaulted into the public spotlight because of their position, wealth, or the timeliness of their work. If there is a voice for everyday Detroiters, I can't think of one.

Sharing cultural ideas in Detroit I think it's pretty common for ideas to be shared in Detroit. Detroit feels like a small town for a city its size and word travels fast here. What's problematic is that information doesn't travel across different types of communities. What the artists are talking about and learning doesn't really get co-mingled with what business leaders are talking about and learning, for example. Our city exists in social silos. If you want a deep and thoughtful explanation of how the siloed-ness matters, talk to Chad.

Forming new cultural ideas in Detroit In my observation, Detroit is mixed when it comes to forming new cultural ideas. Most Detroiters seem to be resistant to the notion of engaging in the realm of ideas, and aren't good at it anyway. (Go to panel discussions with public Q&A to witness the difficult Detroiters have with asking deep questions.)

Instead, the focus of most Detroiters I come across - not that it's a bad thing, necessarily - is how to get something done. It's about executing and not exchanging at a deeper, more reflective level. There are a few exceptions to this, there are a few groups of people who seem to step back and reflect: artists / writers and the people in Venture for America or other cohorts like VFA. It's funny, a lot of the more reflective people I've come across weren't brought up in Michigan.

In addition to all this, public figures don't seem to be reflecting much and communicating narratives that give social permission to reflect and "ask why." More to come on this in a few weeks. If leadership in the city is razor-focused on execution (with little room for reflection) why would individuals give it a go?

Next, a look at interaction channels.

Enabling the original transmission of cultural ideas From my observation, it seems like there are plenty of ways to originally transmit cultural ideas, although, lots of these mechanisms are through digital channels or through a job (e.g., twitter, kickstarter, a company initiative, artist galleries, etc.) It seems as though there aren't really many physical spaces or social settings to express cultural ideas that are broadly accessible. This is somewhat problematic because Detroit is a city that is not extremely digitally savvy.

Moreover, using digital mechanisms to express a cultural ideas is self-selecting process because it's very public. Because digital channels are very public, it makes it difficult to express provocative ideas without sterilizing them for broader consumption...there's some lost intimacy and nuance.

Enabling the dissemination of cultural ideas There aren't many mechanisms to share ideas broadly, mechanisms for broad sharing are fractured. First, media channels have very pointed audiences. Everything from Crain's Detroit Business to Hell Yeah! Detroit) has a niche audience. We even have two local papers which prevent multiple points of view from being expressed on a single opinion page. Having niche mass media channels prevents ideas from being shared widely across different communities in Detroit and prevents those ideas from bumping up against each other.

Second, social networks don't exist across communities. This prevents ideas from percolating both in the physical and digital worlds. Ideas can't get legs across communities, so they stay within sub-groups which limits Detroit to only having sub-cultures.

Enabling the evaluation and reflection of cultural ideas Just as people don't seem to be reflective on their own, there aren't really formal mechanisms for evaluation and reflection either. We don't have ways to give feedback to city institutions, nor do we have many things like Fail Fest or Nerd Nite. There also aren't a ton of third spaces (public, semi-private, or private) which foster reflection. Moreover, the third spaces that do exist require reliable transportation to reach...something many Detroiters don't have.

This post is already rather long, and recommendations are supposed to be short and sweet, so I'll keep it that way. I'll publish some more specific proposals soon. For now, here are some things we can do (broadly speaking) to improve the possibility of forming culture in Detroit, given all this analysis:

- Model and highlight behavior which give individuals the social proof to express cultural ideas

- Bridge the digital divide so a wider group of Detroiters can engage in the sharing of cultural ideas

- Take pauses in the execution of projects for the public to weigh-in on implementation plans, allowing the new cultural ideas to bubble up

- Create public opportunities (forums) for everyday Detroiters to express themselves and transmit cultural ideas

- Bridge social circles through a consistent series of accessible public events, creating the networks which could broadly disseminate cultural ideas, eventually

- Create opportunities for individuals and organizations to share learnings , focusing on reflections and not strategic planning - this will compel presenters and listeners to evaluate and reflect on cultural ideas

How Cultures Form, Part I - Frameworks for Culture

What is a culture? lt's surprising how difficult and inconsistent definitions of "culture" are. I mean it in the context of organizational culture, and I'll put forth one I found here, which is:

"A set of understandings or meanings shared by a group of people that are largely tacit among members and are clearly relevant and distinctive to the particular group which are also passed on to new members (Louis 1980)."

There's also a widely accepted model from Schein which breaks culture into three levels: artifacts, beliefs / norms, and assumptions. I pulled a nice graphic explaining this from a blogger named Patrick Dunn. You can see his original post here:

But, the more important question here is, how do cultures form? Or, here’s a link to some thoughts on a different (but relevant) question: how does one actually build a culture?

How Cultures Form I've done a bit of research on the question of how cultures form and have done my own thinking on the matter. How cultures form is surprisingly simple. Generally speaking, it's a three-step process.

I use the term cultural idea to include representations of culture at any level of Schein's model - artifact, belief / norm, or assumption. Think of a cultural idea as a value, a physical object, belief, a way of thinking, language, or anything else that represents a culture...it's a broad, inclusive term:

Express Cultural Idea - The process starts by someone expressing an idea through some medium...whether it is a belief, an object, an action, a document etc.

Share Cultural Idea - The process continues when cultural ideas are shared within the group where the culture is forming. As more people accept and internalize the cultural idea, the culture grows

Form new Cultural Ideas - Once a cultural idea is expressed, people form new ideas which contest or reinforce other cultural ideas. Once shared, the process starts again. With each cycle, prevailing cultural ideas become reinforced. The ideas that get reinforced the most become part of the culture

Note that this process of Express -> Share -> Form has to be isolated from other cultures. Without some means of isolation or boundary between the group in question and others, cultural ideas wouldn't be able to reinforce each other. In Detroit this is a geographic boundary from say New York, or Chicago. Unless there's some separation from other cultures, no unique culture can form.

Also, note that for cultures to form, there's activity or structure required to move from step to step. I'll call these mechanisms Interaction Channels. These interaction channels provide the human interaction needed for cultures to form. In other words, if culture doesn't form in a vacuum and requires interactions between people, then there has to be different mechanisms to interact with other people. The mechanisms in these channels different types of interactions required for cultural formation: transmission of cultural ideas, dissemination of cultural ideas, and reflection on cultural ideas.

Transmission of cultural ideas - ideas have to get out of peoples' heads to be able to form and shape culture. Some example mechanisms for transmission are: blogging, social events, art, conversations, strategic plans, interactions in public spaces, mission statements, etc.

Dissemination of cultural ideas - ideas have to be amplified to reach the critical mass of awareness to be able to influence culture. Some example mechanisms for dissemination are: mass media, press events, word-of-mouth, social media, community organizing, etc.

Reflection of cultural ideas - ideas have to evolve and refine for some ideas to reinforce the prevailing culture. In other words, people can express ideas that they never reflect on and form in their heads. Some example mechanisms for reflection are: journeys into nature, community dialogue, third spaces, social media, and story telling.

Interaction channels could also take a few forms. Check out a list (e.g., rites, rituals, gestures) here.

How To Form Culture in Detroit - A Teaser So, to form a culture in Detroit (or anywhere) it's is simple and complicated as fostering these expressing, sharing, & forming behaviors, and, building up interaction channels.

The Magic of Third Spaces, Written From Detroit

I am sitting in a coffee shop and the world is abuzz around me. By now, it's cliche to spend a morning camped out at Great Lakes Coffee - a less than three year old bar and coffee shop in the heart of Detroit's Midtown neighborhood - because it's a well trodden establishment for the city's burgeoning "creative class." But that doesn't make it any less impressive. There are medical students studying in their scrubs, and older men and women conducting meetings in suits. There is a gentleman in a beanie who is wearing a long-sleeved t-shirt with the emblem of a plumber's association. There is a college student in headphones eating Sun Chips. Behind me, the guys who tried to bring the X-games to Detroit and who are launching the ASSEMBLE festival are having a working session. All these people are certainly not a full representation of Detroit's residents, but, it's much more so than most establishments.

This ability to gather, to learn, to work...to dream amongst other dreamers and serendipitously meet them is the magic of the third space.

These semi-public spaces are essential for the development and creation of knowledge, the sharing of ideas and relationships. Third spaces like coffee shops have the openness to bring disparate people into proximity, but have the structure to be focal points of activity. They are respites from the corporate jungle just as they are offices for bootstrapping entrepreneurs and students. They are mixing bowls which mash up different kinds of people with different kinds of ideas - a necessary ingredient for creativity and innovation. Third spaces are community centers, laboratories, and parlors all at the same time. They just happen to serve coffee.

At the same time, these third spaces are not Detroit's savior. There is certainly a carrying capacity for how many third spaces can healthily exist in a city, and they don't create many jobs. They are not accessible to all, either, because not everyone can afford designer coffee or membership fees. But they are a necessary part of a city's social fabric, that creates the right condition for learning, sharing, creativity, and entrepreneurship to occur.

What I hope is that the people sitting in these coffee shops and other third spaces are dreaming about more than just opening other coffee shops and other third spaces. I hope they are thinking about new products and services, philosophies and expressions, businesses and innovations.

And in Detroit, I think we are.

Reimagining Business School Rankings

From what I can tell, rankings are hugely important to the staff and administration of business schools. Rankings, after all, are what prospective students often use to judge the quality of a business school and the value of the $100k+ they spend to complete their graduate education. The one part of business school rankings that aren't really talked about - which I'd argue is the most important - is the methodology of the rankings. Looking at the methodologies is important because different people value different things about business school, so the ranking is only valuable if you value the same things as the people who created the rankings. It's funny that there's little discourse about the formulas for the rankings, no? In fact, I suspect that people talk considerably more about the College Football Bowl Championship Series methodology than they do about the methodology of business school rankings.

After looking into the rankings' methodologies, here are some of the criteria I found. Each ranking uses different combinations of criteria, of course:

- Salary of the graduate's job 3-5 years after graduation

- What recruiters think about the school

- What other business school faculty think about the school

- What students think about the school

- Rates of faculty publishing in major journals

- Rates of graduates being placed into jobs after they graduate

- GMAT / GRE / GPAs of incoming students

- Diversity of the class

- Quality of alumni network

For more details, here are the links to the methodologies of various rankings: The Economist, US News, Financial Times, Forbes, Businessweek

What I propose is that there are other metrics that matter, that could better demonstrate the quality of the school and give a flavor of the priorities of that school's administration. Here are some measures I'd be curious about...ones that I'd consider measuring if I were making the ranking:

- Percentage of students who go to jail (this is what sparked the idea for this blog post, I was talking with two classmates about this)

- Percentage of students who become c-level executives

- Number of VC dollars raised per student, number of startups launched per student

- Number of students who are single at some point during their studies who end up marrying classmates or alums

- Percentage of graduates who feel happy / fulfilled in their work 5 and 10 years after graduation

- Percentage of graduates who enter non-profit or public service careers for a period of time within 5 years of graduation

- Effectiveness of graduates as rated by their peers and/or subordinates at work

To assess whether a business school is doing a good job preparing its graduates for business careers, we ought to have a broader set of measures. I wonder what the rankings would looked like if we prioritized holistic measures in addition to or in lieu of what the rankings currently measure.

Jargon vs. Slang - And How We Treat Them Differently

Let me start by saying this post is an observation. I don't intend to make an explicit point. That said, I think this is a topic that many regular readers of this blog have an interest in. With that in mind, I invite you to share your opinion or add your observations in the comments. If you like, I'll even update the postscript of this post with your text (anonymously if you like). If you want to add your story to the text of the post, e-mail me: neil dot tambe at gmail dot com.

An observation: we evaluate jargon and slang differently

I was out with some friends, and because most of them are former (or current) teachers in Detroit we often discuss topics related to education or their students. This past weekend, we started discussing some of the slang used by Detroit students. Here are the highlights:

- "You're telling a story" or "You're boostin" = You're lying

- "That [shirt, or something else someone is wearing] is crispy" = That [shirt, or something else someone is wearing] looks really good

- "Why are you finessing my shirt?" = Why are you stealing my shirt?

- "What up doe" = YES, I AFFIRM WHAT YOU ARE SAYING AND IT IS GREAT, or, what's up?

For a moment, forget about any improper use of grammar embedded within these phrases (which I might add, I like some of them a lot...they're fun). Focus on the slang. In contrast, here are some highlights of the corporate jargon I heard (and unfortunately used, sometimes) as a consultant:

- "We need you to take ownership of that work" = We need you to be responsible for that work

- "We're boiling the ocean" = We're attempting to solve more problems than we have the capacity to handle

- "We will start with the marketing piece, then continue with the finance piece" = We will start with the work we need to do related to marketing, and then continue with the work we need to do related to finance

- "I'll reach out next to touch base so we can find a time to connect about best practices we can use for the project" = I will contact you so we can meet to talk about the advice you have (based on your experience) that we can apply to accomplish the goals of this project

Both sets of phrases - the slang and the jargon - are equally contrived and imprecise. If anything, the jargon is more vacuous and sterile. To be fair, the jargon and the slang carry meaning within the communities of their use; the words do give common understanding of an idea.

What is interesting, however, is that we generally perceive the slang as an indication of immaturity and the jargon as professionally acceptable (albeit annoying). We judge the slang and assimilate the jargon, even though the contexts of usage are similar.

That's interesting, isn't it?

Measuring Social Value, Part II – A Framework For Measurement and Evaluation

In the previous post of this series, I proposed that we don’t have a sound theoretical framework for understanding forms of non-economic value creation. Because we don’t have a theoretical framework for understanding non-economic value (e.g., social value) we don’t have tools to measure and assess our efforts to create it. In turn, we aren’t very good at addressing social problems. As I mentioned in the post, Business Must Do Good, social value is all about happiness. So any framework for understanding social value must aim to explain happiness, which I’ll call “welfare” in this post. For those of you who are economists, you can think of welfare as an analog for consumer and producer surplus.

For now, I’ll go straight into a work-in-progress framework for understanding social value (i.e., welfare), leaving out much of the theoretical underpinnings. I’ll save those for a subsequent post. Needless to say, it’s a little complicated. There are several types of social value (e.g., physical health, intellectual engagement, social engagement, emotional health, etc.). For the sake of introducing the framework, I’ll focus on physical health.

A Framework for Social Value Creation

What’s different about social value, is that it’s not always best to maximizing or minimizing a certain quantity – like some abstract measure of physical health, like resting heart rate or weight. For social value, it’s instead important to be in balance between extremes. Moreover, it’s not always about absolutely quantities either, sometimes welfare is derived from comparisons between an individual’s level of welfare versus another person, versus their aspiration, or versus their perception of their level of welfare.

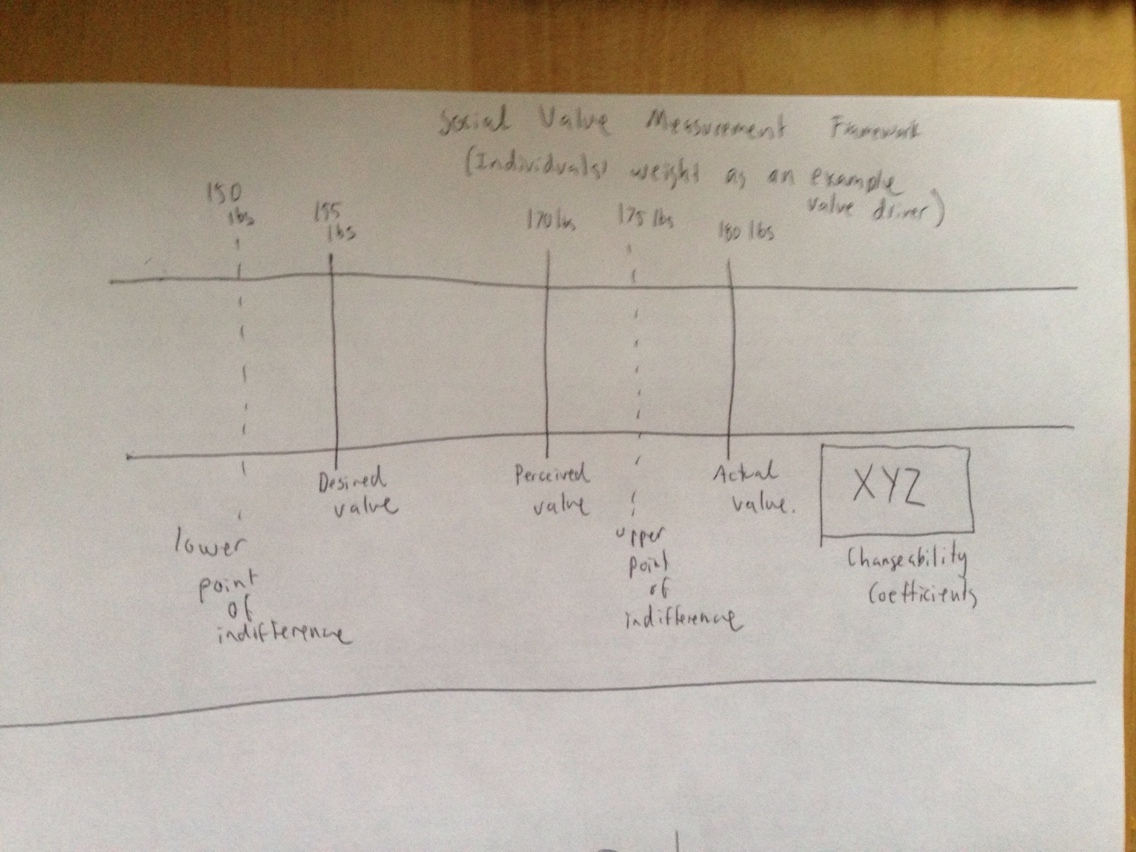

These observations are the basis of this framework, which is how I propose we conceptualize social value. I will explain each part of it in turn:

Overview: This is a horizontal bar and not a wedge, for a reason. I don’t thin social value should be measured implying more is better than less, it’s all about meeting expectation, being in balance, and having equity between people…because that’s what makes us happy. This bar is a simple way of plotting out certain types of information in a cohesive way, and what is important to interpret is how these quantities of welfare relate to each other.

The bar as a whole is a range of possible levels of welfare for some value driver, in the realm of physical health maybe it’s something like resting heart rate, blood pressure, weight, or some quotient between the three.

Points of indifference: I have plotted upper limits and lower limits of indifference. By this I imply there are values where it doesn’t matter so much if one has more or less welfare. Take resting heart rate or weight for example, if you’re in a certain range you’re considered healthy and it doesn’t really matter if you’re within that range. When you fall outside that range, it’s not a great thing.

For individuals, the interpretation tactic here would be to see whether people fall inside our outside this range of indifference. For societies, you could evaluate – in aggregate – what the distribution of people across the value driver is…say in a histogram. You could also look at whether the range between the indifference points is increasing or decreasing.

Desired Point, Actual Point, and Perceived Point: Think of this using the example of weight. On this horizontal bar, different people would have different desires of where they would want to be, where they actually are, and where they perceive they are. Plotting these points would provide insights on whether people are actually happy because you could evaluate the gaps between these points.

For individuals the interpretation tactic would be to look at the gaps between desired points, actual points, and perceived points because they would give some indication on how happy that person is (because a lot of what makes us happy is whether we are getting what we desire. For societies, you could aggregate and look at centrality and variances measures for these values and the distances between them.

Ability and Perceived Ability to Change Actual Point (Changeability Coefficients): A final component that affects our happiness is whether or not we have the agency to change our actual life outcomes. Again, think of weight as an example – if we think we can’t change our weight or actually can’t change our weight and we want to, it make us unhappy.

You’d have to measure this as some sort of coefficient or rate and represent it in some way (explicitly or maybe changing the color of the graph to represent different coefficients). You could measure this at the individual or aggregate level.

Next Steps

After explaining this framework, I know there are at least two open questions. I will attempt to slowly build on this model by addressing them in future posts. They are:

- “Weight and blood pressure – the examples you gave – are only two of many, many, things that affect happiness and social value…what types of things would you measure?”

- “Let’s say you could determine different types of things to measure. How would you actually collect and analyze the data?”

I also invite you to challenge my ideas a lot. This is a huge idea and I want to work collaboratively to get it right. If we, together, do get this idea right…it sincerely and wholeheartedly believe it could provide the foundation for groundbreaking work.

Once I’m able to articulate the complexities of social value, I’ll move on to Civic Value and Spiritual Value.

Measuring Social Value, Part I – Understanding The Complexities of Non-Economic Value

You Can’t Manage What You Can’t Assess (And Measure) A few months ago I introduced the notion that Business Must Do Good. Urban Innovation Exchange even picked up the post. In that post I proposed that there are four kinds of value that can be created: economic, social, civic, and spiritual.

These types of value creation are inevitable in the organizational world. As businesses, governments, NGOs, religious organizations, and others consume resources to operate, they will inevitable create and destroy value. Some of that value will be in each of the four realms I have described: economic, social, civic, and spiritual.

We can’t manage value creation in each of these realms unless we assess them. Without some form of assessment, categorization, and measurement we will not be able to proactively take steps to create or destroy value in each of these realms. As a result, even though me may want to create social, civic, or spiritual value, we won’t be able to intentionally.

In short – you can’t manage what you can’t assess (and measure). And by that I don’t mean that we have to measure social, civic, or spiritual value and convert it into a dollar value. In fact, I think that’s a foolish exercise that can’t be done. This idea is so important (and so misunderstood), I’ll focus on the relationship between economic and social value in a subsequent post.

Since we want to manage (and foster) the creation of social, civic, and spiritual value, it’s absolutely essential for us to assess and understand it. This is to say that we need to measure value.

Many have failed in attempting to assess non-economic value. Now, I’d like to present a new approach.

Better Approaching the Assessment of Non-Economic Value

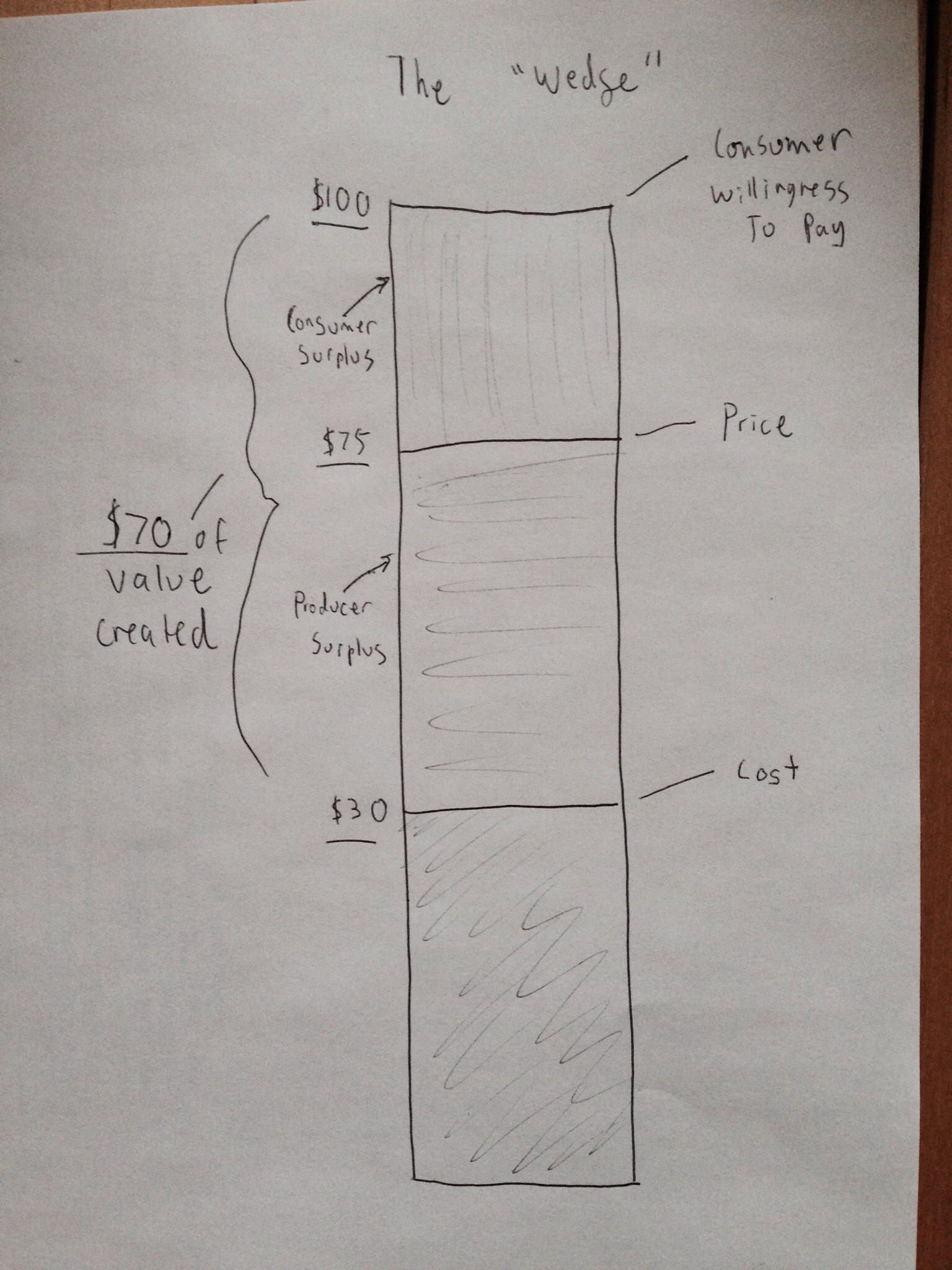

We have some really good tools for understanding economic value. If you take an introductory strategy class in business school, you’ll quickly learn about the wedge as a framework for understanding value.

In short, economic value is the difference between how much a consumer is willing to pay for something minus its cost. Here’s a visual explanation, it’s called the “wedge”:

Everything in business tries to affect these parts of the wedge to create more value. Because creating (and capturing) value is the goal, there are all sorts of things to measuring each aspect of this diagram, people study this stuff like crazy – whether it’s how to optimizing pricing to figuring out how to accurately define how much a customer is willing to pay, and more, not to mention oodles of ways to measure costs.

The point is this: because managers measure willingness to pay, price, and cost – and study it like crazy – they are able to analyze what’s preventing them from creating value and change something to create more value. The tools of business require measurement to improve performance. Business tools, it turns out, are derived from this “wedge” because it’s a simple framework for defining economic value.

The Wedge Doesn’t Work For Non-Economic Value

The wedge, unfortunately, doesn’t translate well to non-economic value. Happiness (the aim of social value) doesn’t have traditional "costs" and it’s really hard to measure happiness in terms of dollars, nor does it have “prices” in the same way as economic value.

I propose that this is why we're swimming around aimlessly when it comes to measuring non-economic value: we don’t have a simple way of understanding what social value is. We need a novel representation of social value – like the wedge – except for social, civic, and spiritual value. Once we have those, we can build more sophisticated tools to understand and measure non-economic forms of value.

For the past few months, I’ve been questioning, tinkering, and exploring how to develop a framework for non-economic forms of value. I started with social value. Read the next post in this series to discover and provide feedback on what I’m coming up with.

Detroit Doesn't Have a "Culture" (sort of)

While I was a research fellow at the Center for the Edge working on this paper, two of the most interesting documents I came across were from Netflix and Valve Software. They were in essence, company culture manifestos. What’s important about them is that these documents are very comprehensive and they are written down. These qualifications – that the documents are comprehensive and written down – is important to note. A culture doesn’t matter unless you can describe it specifically, because if you can't it implies that the culture is weak, coincidental and/or inconsistent across the organization. Coincidental cultures, if you will, don't stand the test of time and are more like fads. What's the point if a culture isn't distinct and enduring?

(Here’s a teaser for later in this post – by this definition, Detroit likely doesn’t have a culture because it's not consistent across the city)

I’ve had the privilege of presenting to a few government and corporate executives in the past few weeks. Culture has come up a few times and it’s not surprising – organizations everywhere are trying to build culture because leaders are realizing that people management (the umbrella category for things like culture and talent) is a sustainable competitive advantage.

But I think a lot of organizations have the wrong approach when it comes to organizational culture. Instead of building and evolving what they have, and create something unique to their organizational challenges and strengths, they try to copy someone else’s culture. The tech sector is often the target of this mimicry, whether it’s copying the practice of rotational programs or having snacks on every floor.

The 1993 Disney film Cool Runnings (which is especially timely because the Olympic winter games are currently occurring in Sochi), offers a parable for why it's important not to mimic someone else's culture.

Recall the scene where the bobsled team is in the Olympic village preparing for their big race. Derice makes reference (per usual) to being like the Swiss sled team. And after an exchange Sanka replies exclaiming that the team won’t be able to perform at its best unless they stay true to what they are: Jamaican.

This lesson also applies to organizations. Organizations can’t do their best unless they stay true to who they are. It takes too much effort to try to be something your not, and that’s effort that can’t be accomplishing goals. If you don't act like yourself it's also hard to be confident - you never know if someone is going to pull the curtain away and reveal you are a fraud.

So when I see companies trying to “build culture” and achieve results by copying the practices of what others are doing, I think they are missing the point. What matters about culture building is doing things that represent who you are, and implementing programs that affirm that identity, not transplanting a practice from another company and forming an identity around that. Copying someone else's culture just isn't sustainable.

I'd argue that being able to articulate a culture comprehensively in writing is a good indicator that the culture is distinct, authentic, and sustainable. If it's not possible to do so, the culture probably isn't sustainable.

Detroit’s Culture

First let me say, there’s no document (that I can find) that articulates Detroit’s culture like the Netflix or Valve Software documents that I linked to above. But that’s not the point. The point is whether one could document Detroit’s (or any other organization’s) culture if they tried.

In Detroit, I don’t think we could document a single, cohesive, culture even if we tried. Detroit has at least two worlds (this is actually something my friends and I talk about a lot) But, I think this is a point reasonable people could disagree about. If you disagree, I welcome you to add comments on this page and list out your articulation of Detroit’s culture.

But for a moment let’s assume that Detroit does have a single, cohesive culture and identity. If that’s the case our culture certainly not documented or explicitly identifiable via some others medium. We should try to do this.

Documenting our cultural norms and practices would allow us as Detroiters to argue about what is good and bad about our culture and identify elements to evolve. We could put in systems to amplify the culture (an example of this is type of system would be the Andon cord at Toyota or Google’s CEO signing off on every single hire at the company). We could put in policies to police the parts of the culture that are destructive. It would also be a way for people outside Detroit to get a sense of what Detroit is truly like.

Most importantly though, having a strong culture (that’s identifiable) helps with decision making. When weighing several options – say for how to deal with influxes of investment and development downtown – having identifiable cultural norms helps guide how decision makers should weigh the options. As an example, If equity were a prominent part of our culture, that everyone agreed to, decision makers might choose a less lucrative investment if it was more fair to existing residents. Cultural norms are a decision-making heuristic of sorts.

Now, it’s possible to run an organization (or a city, like Detroit) without a common set of cultural norms and values. There's nothing wrong with having a community of sub-cultures, it can work. The downside is that it leads to conflict. Look at San Francisco and the opposition to tech company shuttles and the creative class in the city. Because of different sub-cultures (that have conflicting values) existing in the city, it is leading to cultural clash.

With this example in mind, we can have distinct sub-cultures without an overarching common set of values, but we will have to resign ourselves to the fact that there will be conflict.

I think there are real benefits for creating an environment where culture can develop. And that’s exactly how I think it happens…you create environment for culture to occur and it develops on its own. In the long-term (at best), individual agents can only influence culture, not prescribe it.

This emergent phenomenon doesn’t happen in places where there aren’t connections across communities and inclusive participation of the entire population. So if we want to develop a unified culture in Detroit, that’s what we should do, make institutions and public dialogue inclusive.

Tackling the unsexy (but game changing) policy issues

I attended a great event last night, put on by the good folks at ASSEMBLE and Chad of Urban Social Assembly. The troupe brought in Vishan Chakrabarthi of SHoP Architects in New York to speak about the views he articulated in his excellent book titled "A Country of Cities." In his talk, Vishan highlighted how national policies have shaped how urban and suburban landscapes have developed in America. The existence of the mortgage interest tax deduction and the construction of interstate highways, for example, made it cheaper and easier for suburbs to grow. I never shy from asking a smart person a question, so I probed the folks onstage (by this point, Craig Fahle was leading a panel discussion with Vishan and a few Detroiters) about whether cities with transit-oriented densities could develop without state or national policy change. Are there any levers cities can pull unilaterally?, I asked.

All the panelists gave interesting answers, including Vishan, but the visiting urbanist also challenged the premise of my question. Millennials, he contended, shouldn't always shy away from big systemic issues and shouldn't balk at the opportunity to shape far-reaching public policies. A lot of these system-wide policies, he argued, are worth tackling because they fundamentally change how the problem can be solved. Millennials shouldn't shy away from these big policy debates because they are hard, complex, and are unlikely to provide instant results.

He's right.

A lot of policies are so deeply seeded in how we conduct business in the US, that they constrain the possible outcomes in the system. Take the mortgage interest deduction - a subsidy on the order of hundreds of billions of dollars a year - as an example. If we're putting intense downward pressure on prices for owning homes, of course suburbs will grow. There are many other unsexy issues like the mortgage interest deduction that have huge impacts on how things work in America. If we don't change some of these things, we may never move the needle on solving some of our country's most difficult social challenges - the ones that millennials claim to desperately want to solve.

As a generation, we millennials crave "positive change" which "leaves an impact" on the world and "makes it a better place." And that's great. But I think we're missing something important if we don't work on some of these foundational issues similar to mortgage interest deductions - like money in politics, emphasis on quarterly earnings and shareholder value maximization, gerrymandering, due process of law, infrastructure investment, budget reform, tax reform, and others.

Maybe the work of our generation should be to tackle unsexy, but game-changing, institutionally-driven, systemic policy changes so our children can do the explicitly impactful work we always dreamed of. Maybe some of us should trade social entrepreneurship for system design. If we did, maybe institutions like governments, markets, and courts would function better in the first place and make some of the gripping social problems we face today less overwhelming to address.

Is Social Entrepreneurship a Middle Class Opiate?

Tunde, a good friend of mine, raised an important question in response to one of my previous posts - Bow Ties, Crazy Socks, and Hip-Hop: Tactics for Successful Intrapreneurship - which I have been mulling over for the past two weeks. He posited: isn't social entrepreneurship just an opiate for the middle class? Though it's possible to dismiss this question as outlandish, I think it mirrors an important debate in the Social - X (fill in the "X" with impact, intrapreneurship, entrepreneurship, etc.) movement...who are social entrepreneurs really serving? Are they serving others or are they serving themselves?

Anyway, I'm glad Tunde brought it up because I think he's right. At very least, social entrepreneurship can be an opiate for the middle class, and that possibility merits preventative action to ensure that social entrepreneurship (or other Social - X's) exist for reasons broader than being an opiate for the middle class.

What I think Tunde means by opiate is that it's an externally introduced activity that soothes the anxieties of the user and distracts them from the difficulties of their reality. Even more extreme, I think he means that the opiate of social entrepreneurship distracts the privileged from the full extent of the issues facing disadvantaged communities. I'll let Tunde weigh in and will update this post with any remarks he adds. For now, this is the working definition of "opiate" I'll use throughout this post.

[Here's a placeholder for Tunde's response. I'll update this placeholder should be reply with any remarks.]

I have often questioned the intention of certain social entrepreneurs, especially those widely publicized in mass-media publications. There's something about the air of those folks which is arrogant and condescending instead of inquisitive and humble. Moreover, some of the innovations presented by social entrepreneurs seem to be surprisingly self interested or misaligned with the real, palpable needs that the intended "customer" actually needs. Here's an example of a misaligned need - as told through a recount of why Bill Gates is less than amused by Google's (and others') attempts to provide internet access to the global poor.

It is this behavior - serving yourself more than serving others - that I see as the hat tip for social entrepreneurship as an opiate. This is because not serving a customer's need shows that you're interested in soothing yourself than serving another. Maybe Social Entrepreneurs are interested in looking cool (which is entirely possible when you're looking to get press to satiate a high-profile funder, rather than depending on a customer's payment to perpetuate your existence). Maybe social entrepreneurs hate their corporate job and hope social impact will alleviate their need to do something meaningful or interesting with their time. Maybe they're just curious people who think social entrepreneurship will allow them to travel to interesting places across the globe. The reason for "opiating" themselves - if that's what they are doing - could be anything. It's certainly possible.

What's more important is that this "opiating" I've described is presumably harmful. Like I said before, the processes of selfish social entrepreneurship could distract from real, needed social interventions by conveying the perception that the needy are being served. Perhaps more importantly though, is the chance that the growth of social entrepreneurship is a symptom not of social injustice but the disengagement of most workers from more traditional forms of employment.

Let me explain. In some senses, social entrepreneurship could be an opiate because it makes social entrepreneurs feel good and/or helps distract them from the fact that high-minded social interventions are all that matters in improving social outcomes for the world's most disadvantaged. But the "opiate effect" could also be people trying to make up for the fact that they hate their jobs and feel disengaged from them. (Note, I don't think disengagement is a good metric, but it's the most easily accessible to make this point right now.)

I'd like to note, I'm not suggesting that all social entrepreneurs are selfish, and self-aggrandizing. I'm merely suggesting that it's very reasonable to think that social entrepreneurs use their craft as an opiate. Moreover, I'm suggesting that because there's a clear path to using social entrepreneurship as an opiate, and that using social entrepreneurship as an opiate might indicate a presence of harm, we should be intentional about alleviating that harm.

I think there's at least one simple way to prevent social entrepreneurship from becoming an opiate for the middle classes: have real, authentic experiences inform efforts to pursue social entrepreneurship. In my limited forays to deeply understand social ills, I've found that - by experiencing the "front-lines" - it's not only informative, it's also humbling. Without understanding real, front-line needs, it's very easy to have a ivory-tower-esque solutions which are well received at cocktail parties (and well intentioned) by those who have no idea what's really going on in the lives of real people. That's where the disingenuousness fixes itself - by trying to understand the issues of real people (being "close to the customer", if you will) it's much easier to take effective, authentic intervening action.

Here's the rub, though.

The larger, and I suspect more transformational, opportunity to improving both employee and societal welfare is to give people ways of making an impact in their corporate jobs. That's why my focus is starting to shift from social entrepreneurship to social intrapreneurship. Through social intrapreneurship you have more resources to do good and you can generate more social returns that way. It's just not as sexy to talk about.

---

But enough of my opinion, what do you think? Does anyone even reject the premise of the question? I'd love to hear what you think.

My Race, In My America

Before this post, a statement:I've grappled with my racial identity, especially because I'm the first person from either side of my family to be born outside of India, my whole life. I'd like to share some of that reflection.

I'm fully aware that this is somewhat narcissistic and that race is a caustic subject. With that in mind, I'd like to qualify this post by saying that I will try to avoid making accusatory statements or speaking in platitudes about race in America. This post is about my experience. I know that my experience is but one of the many entirely unique perspectives on race.

I'm also qualifying this post because I'm tense about backlash. After all, I am recruiting for internships and future employers or business partners may not take too kindly to someone who is so "controversial." Perhaps though, that's exactly why I am writing this...because I feel like I have enough built up rapport to be able to withstand any social consequences which may arise. Not everyone has that luxury. I'm often naive about how my ideas will be received, I hope this isn't one of those times.

What all that said, if you have a thoughtful comment please do post it. I'd love to hear criticism of my perspective, for one. But also, I feel like if there are thoughtful comments it will do two things. First, it will demonstrate - in a small way - that it's possible, in America, to have nuanced, civil discourse about sensitive subjects. Second, it legitimizes this blog post, which will make me feel less vulnerable to social consequences. I admit that the second reason is selfish.

-Neil

And now the post.

---

"My Race"

There is no greater identity that has shaped my life than that of my "race." I use quotation marks here to make a point - that race is a social construct. Unfortunately though, it's a construct that feels real, daily. First, a bit about my racial identity.

I categorize myself as an Indian-American. I was born in the late eighties and I was the first person on either side of my family to be born outside of India. My parents, who I love dearly, are immigrants from Madhya Pradesh, a state in the heart of the country. Almost my entire family still resides there. I call my cousins brothers and sisters and most people think this is peculiar at first listen.

Race has colored my life in many ways, but it all comes down to one notion: I don't feel like I belong anywhere. I like hip-hop, but I was brought up speaking Hindi. I am decently good at math but I deferred a career in engineering or medicine. The values of my family make me relate more to practicing Christians than to Bollywood, even though I haven't been baptized and I don't take communion at Catholic Mass. I could continue with more examples, but the point is I'm always somewhat on the outside of a demographic group. I don't quite fit in, for one reason or another. There is never a time where I can comfortably fade into the background of a social setting. There's always something about me that sticks out, and it's often my race.

"My America"

Before I was born, there were lots of efforts to prevent institutional racism in America. Suffrage was greatly expanded. The poll tax was eliminated. The Civil Rights Act was passed. Diversity was written into Supreme Court jurisprudence as a compelling state interest in higher education. The list goes on.

But I still have the lingering feeling that America is too quickly trying to forget about it's race-riddled past. Changing policies is one thing, but changing hearts and minds is entirely another. On this point, here are a few examples illustrating when I've felt tremendously like a minority.

I grew up in Rochester, MI. It's a good town with generally good people. I went to good schools and lived a good life, I won't contest that. After I went to college though, I started noticing things when I returned to Rochester over Christmas vacations. People looked at me differently in public places than they did in Ann Arbor and seemed to be more guarded around me than they were my white friends. Once a woman with a baby brushed by me rudely as I held a door for her at a Thai restaurant. As her husband walked by, he whispered to me, "I'm sorry."

It was the first time I realized the gravity of what being a minority in America was. Yes, I suppose that woman could have been rude to me for any number of reasons and that her husband could have apologized for any number of other reasons. But for my white friends who are currently perplexed at my propensity to "play the race card," know that you begin to develop a "race radar" when you're a minority. You start to be able to decipher when people are treating you differently because of your race and when they aren't. I can't explain it. It's just an intuition that develops over time.

To underscore this point, I can't remember the number of times that people have talked to me like I don't understand English or change their tone of voice when I'm ordering a meal, relative to when my white dinner partners are. It often disgusts me how cashiers behave toward my father - who has a thick accent, still, but is one of the most educated people I know. My mother, who owns a small retail shipping business, has been slandered by angry customers who call her a foreigner and say that she "doesn't belong in this country."

To be fair, some of my mothers customers have defended her in the face of bigotry, and I don't have enough love in my heart to give to those folks. But based on my experiences, it's laughable to think that America is a "post-racial" society.

One final story, and a conclusion

The most recent instance of really feeling my race was at at a previous job. As a bit of context, know that Asian cultures are often more deferential to authority figures, like supervisors. American companies expect more upward management and expect that employees are more outward with their opinions and more aggressive about managing their careers.

I received an invitation to a webinar for Asian employees. It was a straight-talk panel in which more senior Asian managers would talk about how they managed their careers. The description of the webinar indicated that the panel would be giving tips on how Asian employees could learn to speak up and adapt to the culture of the company. This was fine advice, but to me it sent the signal that there was something wrong with me and that I had to change something about my nature/demeanor to be more successful at the company. What I've never seen in the corporate setting is a webinar for white managers to give them insights on how to better adapt their styles to get more out of Asian employees. The responsibility to fit in lies with the minority.

The company, is actually quite progressive with regard to diversity and inclusion, and this instance is only a subtlety. But it's powerful one. It's examples like this - that pervaded my experience growing up in America - that signal to me that there's something wrong with me as a minority. That's it's my responsibility to assimilate. That I have to choose between being who I am and having a healthy and prosperous life. That there are bounds on the type of person I'm allowed to be.

This is the most insidious aspect of race, because it subversively shapes the narrative you can create for your own life. Yes, it's not overt and it's not institutional but this shackle is just as powerful. It's a like a poll tax on your own psyche. And, yes, all the victories of the 20th century were instrumental for making America more equal. But the way I see it, and the way I feel personally is that I'm living with an unshakable feeling that there's something wrong with me because I'm not white. I feel like I'll never be able to be part of the club, because of the implicit attitudes of the country we live in.

Then I realize how lucky I am because of the family I was born into. And then I realize how hard it must be for minority citizens who didn't have as much of a head start as I did. It's a peculiar confluence of feelings.

Finally, let's assume for a second that we've made every institutional change that we need to make to ensure a fair and equal society. My gut tells me this isn't true, but let's assume it. Under this assumption then, I propose we set our sights on the next challenge of changing narratives about race, instead of claiming that race isn't really an issue in America anymore.

How might we ensure that every person in America doesn't feel like the possibilities of their own life aren't constrained by who they were born as? How can we help people change the narratives they create for themselves, for the better?

How "core" must social intrapreneurship be?

I came across this article today from Bill Eggers of Deloitte. The article gives several examples which suggest that true social innovation / intrapreneurship occurs when a business adapts one of its core activities to provide social good. This is in stark contrast to traditional CSR which takes ancillary activities or resources and directs them for social good. For example, a core activity is Wal-Mart greening its supply chain. A periphery activity would be Wal-Mart employees mobilizing a company-wide clothing drive to make donations to local charities. See how one is part of regular operations and one is a supplemental activity?

I kind of think that the sort of change we should be after needs to be as close to the "core" business as possible. So that a business is simultaneously creating economic and social value...rather than creating economic value, feeling guilty, and then doing something social to make up for it.

I don't see a moral distinction, and I think it's cool if business wants to make an impact by having its employees volunteer or donate stuff. And, for what it's worth, skills-based volunteerism seems to be somewhat "core" because of the learning gains employees receive.