Supplement to "How To Actually Build A Culture - What I've Learned"

A supplement to my post "How To Actually Build A Culture - What I've Learned".

This post is a supplement to "How To Actually Build A Culture - What I've Learned"

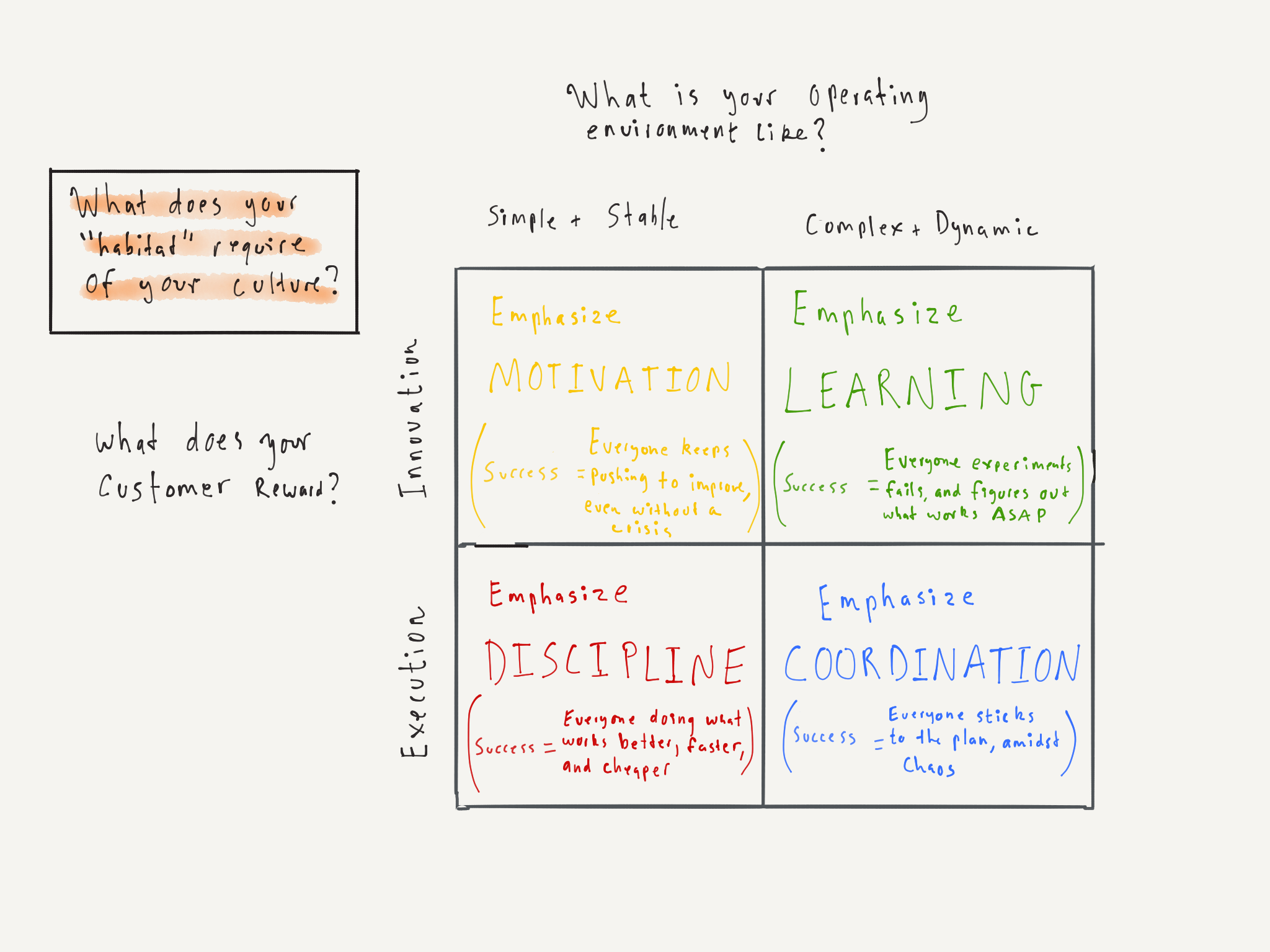

Determining your company or team’s habitat is not a trivial pursuit. Ask yourself these two questions:

- What do your customers reward – execution or innovation?

- What is your operating environment in your market niche - simple & stable or complex & dynamic?

Of course, answering these questions is not trivial either. Here are some other guiding questions to help you come up with the right answers:

What do your customers reward – execution or innovation?

- Is your customer always going to what’s new?

- Are your customers fixated on price or quality?

- How often do your customers expect new products and services?

- Do you have a fan-base of early adopters in your market niche?

- Do customers know what they like and demand it?

- Are customers dissatisfied or bored with what companies in your niche offer?

What is the operating context in your market niche – simple & stable or complex & dynamic?

- Is your company or team divided into a lot of geographies or divisions?

- Do you interact with a lot of partners?

- Is there a new regulation that’s causing everyone to change?

- Is there a new technology that’s disrupting the status quo?

- Do customers have a lot of power when they’re making choices?

- Are there a lot of new entrants to your market niche?

Management Is A Technology That Needs Upgrading

At work, we've abandoned typewriters and horses & buggies, but we still use management practices that are nearly a century old.

So much of how we operate at work is settled on because that's how we've always done it. In the past few weeks I've had a heavy hand in shaping a team, which is why I've been reflecting on the topic. I don't yet know the best way to build a team, but what I do know is that in most cases, conventional wisdom is totally wack.

Rather than prescribing an "ideal" way to operate a team, I think different situations require teams with radically different operating systems (e.g., the way a team focused on responding to a natural disaster should work and feel is likely much different than how a team staging a play should work and feel). That said, corporate environments tend to have a few standard features, that don't often make sense for today's operating environment. Here are a few examples:

ORG CHARTS

Most teams I've been on are obsessed with organization charts, even though they don't say much. Org charts, after all, leave out mission / purpose, the roles on the team, the relationship across organizational units, and norms on how decisions are made. People seem to make them just because they think they're supposed to.

In my experience, org charts are helpful only for identifying who gets to resolve disputes during a turf war. I'd add, that org charts are a calling card of a hierarchical bureaucracy (a form of organization designed to avoid change), which is precisely the opposite of what today's operating environment requires. If you have a manager that insists on having an organization chart for the sake only knowing "who reports to who" - that's trouble.

STATUS REPORTS / STATUS MEETINGS

Most status meetings I've been to are a colossal waste of time. Usually managers have them for the sole purpose of making it easier to report to their boss, who is invariably an executive. If a team's manager is having a meeting for the sole purpose of checking on work, they are probably a terrible manager - a manager should know that already.

I'm not suggesting that teams shouldn't meet. What I am suggesting is that they mostly likely need to meet for reasons other than reporting on progress - like coordinating complex tasks, raising issues, or sharing learnings. If you have a manager that holds a "status meeting" and the manager does most of the talking, or it's basically a sequence of 1-1 interactions between the manager and each direct report - that's trouble.

INTERNS / JUNIOR STAFFERS

Lots of teams I've been on, treat interns and / or junior staffers like garbage. This is not only frustrating to the intern and a crummy thing to do to another human, it's a waste of talent.

To me, how teams treat the lowest colleague on the totem pole is a measure of that team's morality and their effectiveness. After all, if the way a manager under-utilized someone's talent solely because they're the youngest, newest, or lowest paid - it probably means they're not good at utilizing anyone's talent. If you're on a team that treats interns poorly - that's trouble.

I don't mean this post, entirely, to rib poorly run teams or incompetent managers. I've actually been lucky to be on more than my fair share of highly effective teams with effective managers. What I'm suggesting is much more radical. I'm suggesting that everything about how today's teams are built and how they operate should be questioned. So much of how organizations operate today is solely because "we've always done it that way".

To me, management is just like a technology. Computers are a technology for manipulating information. Rockets are a technology for traveling to space. Management, similarly, is a technology for coordinating a group of people toward a common goal.

Most organizations no longer use typewriters, horses & buggies, or quills & ink. Consequently, I think it's absolutely ludicrous that most organizations still use management practices that were pioneered almost a century ago. It's time to think more deeply about the technology of management.

The way I think of building teams and organizations is how I understand genes. In a living organism, some genes control eye color, some control height, and some control sex. Depending on how those genes are combined, you get a different kind of organism.

I think of teams the same way. Organizations have "genes" too, but in management we call them "norms". Some norms control size of the team, some control communication practices, some control conflict resolution, and some control how feedback is delivered, and so on. Depending on the goal and context, different teams need different genes.

Most managers act as if the norms of teams can't be changed - they just take what they've seen before and replicate it. That's a tragic mistake that's usually bad for the company, bad for the team, and bad for customers.

How To Solve A Problem

I put together this mind map on how I've come to approach problem solving. Credit goes to the many mentors I've had in the enterprises of problem solving and innovation.

How do you solve problems? What's your critique of my approach?

How To Solve A Problem

It Is Time To Build A Boat

Many generations of my ancestors have been preparing me for this moment.

The first thing I thought about when sitting in Culebra, Puerto Rico on the most beautiful beach I've ever seen, and staring out at the ocean was that "Papa would've loved this."

After all, my father had the heart of an explorer and loved natural beauty. I quietly dreamed about surprising him with plans of a road trip tour of the American West - National Parks and all - someday soon, which we'll never get to do now. But regardless of that, he would've certainly been pleased with the breeze, sunshine, and the bluest blue water I've ever seen with my own eyes. That was my first thought.

Then the second thought that came to mind, was, "How the hell did I get lucky enough to get here?"

You see, I'm the only child of two Indian immigrants who grew up pretty poor and really poor. When my parents arrived in this country, they were a bit older than me and they were still struggling, much more than I am now. And there I was, sitting on this remarkable beach, with some of my oldest friends for a weekend jaunt, soaking in the sort of scenery my father dreamed of - all before hitting my 29th birthday.

I got there because I've been lucky enough to stand on the shoulders of giants, benefitting from the accumulated hard work and integrity of probably a dozen generations before me. My ancestors, most notably my parents, brought me to the precipice of where I think damn near every person hopes their descendants will reach someday - on the cusp of making it.

I realized this weekend that I was born at the inflection point of a hockey stick graph. For generations my family has been moving along the shaft of the hockey stick, with things getting slowly, linearly better from generation to generation. And after one last big push from my parents, I'm looking out at a chance to end my family's incremental growth. I'm at the inflection point right before the blade of the hockey stick when things get exponential. I'm right here, at the point of making it that my ancestors - most of all my father - have been working toward for generations.

But I don't even know what "making it" means, exactly. Does it mean becoming wealthy? Does it mean being able to see the world and having opportunities leisure? Does it mean being able to make an outsized impact on the world and move humanity forward in a tangible way? Does it mean doing something which brings honor to my family's name? Does it mean laying a foundation so my kids can have an outsized impact someday? Does it mean living without the shackles of want or oppression? Does it mean having a happy life surrounded by the love of family and friends? Does it mean becoming one with God?

I don't think I'm alone in feeling this way, especially among the children of immigrants. In many ways, we live an easy life. More importantly, we live in a time where I'd guess than many more people than ever before are being born at the inflection point of a hockey stick.

So I am confused about where to go from here. But only confused and not afraid, because my parents taught me well and are with me always (just as all my ancestors are). I just wish I could say, "thanks, Pops." I understand the magnitude of his sacrifice and his greatness now more than ever. He literally and figuratively brought me to the water's edge.

And I suppose that if I'm at the water's edge, it is time for me to look up to the sky for guidance from my father and all my ancestors before me and build a boat.

The ESPN Effect

To me it feels wrong to trust ESPN more than I trust the channels which cover hard news. But it's not surprising.

In my book, ESPN is the most trustworthy news source on television. I've especially noticed this when catching gulps of election-cycle news coverage on traditional news channels in public places like airports or restaurants.

To me it feels wrong to trust ESPN (or other sports media) more than I trust the channels which cover hard news. But it's not surprising.

During sports press conferences, the players and coaches answer questions candidly and admit mistakes. Interviewees on traditional news channels have this arrogant way of misdirecting their answers to sincere questions and reek of poll-tested sound bytes.

In the sports media, the vast majority of stories focus on the "scoreboard" in some way - who's winning the current game, whose offseason acquisitions make them likely to win, and which players & coaches are likely to propel their teams to championships. In sports, to focus media coverage on topics related to winning and losing is relevant and substantive. In my opinion, sports media doesn’t venture too much into locker room gossip (which in sports is a rather frivolous thing to discuss).

Traditional news seems so bush league compared to that. In covering the presidential race, for example, I feel like I hear more about polling numbers and fundraising totals than I do about actual issues. The coverage feels riddled with talk about inside baseball between politicos rather than something substantive.

Finally, sports media tells great stories. ESPN, for example, continues to do amazing documentary work in the 30 for 30 series. Heck, during the Super Bowl I probably enjoy the montages and season-recapping human interest stories more than the actual game. Sports stories have this palpable earnestness and seem to let the truth drive where the story goes. This is unlike traditional news in which the journalists - at least to me - always feels like they are subversively trying to bend the story to their own worldview.

I think it's also worth noting how caring discussions about sports can be. I've heard men in the barbershop passionately argue about sports with remarkable civility. Nobody ever insults their buddy, nor do people hold their opinions as sacred. People actually listen to each other. When talking about sports, I've actually seen people change their minds when presented with better evidence.

Of course, these days, "civil" is one of the last words I'd use to describe discourse stemming from traditional news coverage. I can't help but think the quality of the media companies, and how they approach their work, makes a difference. I can't help but think that because ESPN (and other sports media organizations) approaches its work with integrity and thoughtfulness, it leads to greater civility when everyday people hang out together and talk about sports.

Free Time Is Worth Protecting

48 hours per week is a comically small amount of time to really live.

On February 15, the daily question I asked on Facebook was, "What's one way you're trying to change this year?" I replied:

"Focus more on fewer responsibilities."

I've said this in the past, and failed to focus on fewer responsibilities. This time around, I decided to write down all the responsibilities I have and how much time I spend on them, just to see what I could cut down on. Here's a rough summary of what I budgeted for:

- Sleep - 8 hours / day

- Work - 10.5 hours / weekday (or more) and sometimes more on weekends

- Eating / Cleaning Dishes and General Life Maintenance - 1.5 hours / day

Let me stop there for a second. Those three activities are essential, I can't realistically stop working, sleeping, or eating. Here's what's left:

168 hours / week (24 hours a day x 7 days a week)

- Sleep (56 hours / week)

- Work (52.5 hours / week, at least)

- Life Maintenance (11.5 hours / week)

= 48 hours left per week after accounting for non-negotiable activities

When I plotted this out, I was flabbergasted. Borrowing from the concept of disposable income in personal finance, my "disposable time" every week is only 48 hours.

Which is to say, everything non-essential to staying alive has to fit within 47 hours every week. That includes spending time with Robyn, family, friends and eventually kids. That includes reading and exercising. That includes personal correspondence and all side projects.

48 hours per week is a comically small amount of time to do the things most people believe make life worth living. I'd encourage you to do a similar audit of your own responsibilities. If you're anything like me, you'll be much more protective of your time and attention after counting out the hours.

A Case For Quitting Your Career

Why aren't there more smart people in the industries that matter the most?

In the middle of January, I found myself in the most unexpected of places - the intensive care unit waiting room of a hospital in Philadelphia. My father was very ill and my mind was (obviously) racing. I don't know exactly why - maybe my reaction to the stress was to distract myself by thinking about something else - but while I was there I marveled at the medical devices being used as part of his treatment. And I don't know why, but I started to ask myself, "why do so few smart people I know want to work for medical device companies?"

In addition to reflecting on this myself, I put a few questions related to this topic onto facebook and soaked up what people wrote. Anecdotally, it seems as if there's a mismatch of talent in our country. A disproportionately small amount of the world's bright talents tend to enter industries which have a disproportionately high impact on human society.

But why?

After reflecting on some of the reasons which might be deterring more smart people from taking their talents to an area of greater purpose, here's my no-pulled-punches, call to action to my smart friends: you can quit your career. Join those of us on wacky, non-standard paths.

Taking a pay cut is not that bad

I'll be the first to admit that I grumble about my student loan debt all the time. I'll also readily admit that I'm very lucky to make a good living - my pocketbook is modest, but not hurting. That said though, I took a pretty hefty pay cut when I started my current job. But to all my MBA / Law friends there who feel conflicted about those strategy consulting, I-banking, corporate, big law jobs...don't worry. It's not that bad to live on a budget, especially if your budget is still substantially higher than the income of the average American family. The pay cut is nothing to be afraid of. And besides, a high-paying job or glitzy perks are usually a good indicator that the company is making up for something else about the job that really sucks.

You're not actually learning that much more

Prestigious firms like to talk about how much you learn while working for them. I think that's misleading. First of all, people in smaller or scrappier organizations tend to learn a lot, very quickly because they're thrust with more responsibility. Second of all, I think how much you learn at work has much more to do with your own disposition than the company. People who take risks, work hard, and have a learning mindset learn wherever they go. If you need a perfect company culture to learn, you'd probably get just as much of a boost in learning by staying put and changing your attitude.

You don't need a name on your resume to prove that you've made it

One of the things I've learned is that someone's resume or educational pedigree isn't a good indicator of who I'd pick to be on my team. As many folks who responded to my facebook questions pointed out - there are many kind of intelligence and there are smart people all over the place...that didn't go to elite schools or work for top firms. Don't think you need to work for a so-called prestigious firm to "make it." At the end of the day, your deeds and results prove your character and your talent. Not a line on a resume.

Doing hard stuff is not that scary

I wouldn't have admitted this at the time, but working at a cushy company was really easy, stress-free, work. At the end of the day, my actions didn't have measurable consequences on real people. It's certainly hard to work in gnarly, complex, environments fraught with problems - which tends to be the case in consequential industries. My father said, "There are many problems, but there are also many solutions." I think that wisdom applies here, too.

---

Of course I realize that my examples are hyperbolic. And of course, I'm not suggesting that everyone quit their jobs, move to Portland, and become sustainable food-truck owners, inner-city teachers, design-thinking consultants, non-profit staffers, or anything else that fits this rosy picture of a impact-driven career. I'm also not trying to suggest that the world doesn't need bankers, consultants, corporate lawyers, or people to start cutsy billion-dollar tech companies that don't really serve anyone but the affluent.

What I am saying, though, is that there are too many really bright people (at least among people I know) that are in jobs that are an insult to their talent and that the world would probably be better off if those people did something more consequential.

I don't normally soapbox (anymore) in blog posts and I'm normally not so poignant. I get that, and I get it if anyone reading this feels taken aback or offended by this post. I sincerely apologize for that.

But here's what really gets me, and why I am so vigorous in my passion for this idea. It goes back to when I was in the ICU in Pennsylvania, after spending the last few hours of my father's life at his bedside.

I kept thinking, If more of the world's smartest people chose to build medical devices instead of being consultants and investment bankers, would my papa still be with us?

My 2015 Annual Letter

I hope you'll find that the time you invested in me was worth it.

One of the (only) blogs I read diligently is Farnam Street, founded by Shane Parrish. For the first time this year, Shane followed the lead of many public companies which issue an annual letter to their shareholders. I'm doing the same via this blog.

After all, those of you who read my blog are representative of all the people investing in me and my success - family, friends, colleagues, random strangers on the internet who sometimes follow me on twitter, etc. 2015 was a transformative year for me, and probably the best I've had. Aside from a little luck, it's been a stupendous year mostly because of you all. I honestly don't think I had much to do with it, other than showing up.

So first and foremost, thank you for investing your time in me throughout the year. I am grateful for your influence and caring on a daily basis. I've been doing my best to generate a return on your investment. Here's a recap.

A SUMMARY OF GOOD THINGS

The greatest result of the year, was the moment Robyn said yes to my proposal for engagement. It was truly a moment I have been anticipating my whole life, even before I knew her. It was the end of a long, slog, of a journey as a bachelor which so many folks helped me survive. Over the course of decades, people have been helping me to be more confident, mature, and persistent to find Robyn. Well friends, all your work (and patience in dealing with my shenanigans through single life) has finally paid off.

A few months later, I graduated from the Ross School of Business with a graduate degree. But the greatest result of my time at Ross was not my degree, but the great friends I made there. What's super cool is that these friends are not just interesting people to pal around with. They're thoughtful, courageous, people who have deep convictions about the world...beyond profits and being recognized for their accomplishments*.

People criticize MBA Programs for just being a two-year party where affluent people make the connections to stay affluent. Luckily, I received more than that, I'm now part of a tight-knit crew that really pushes me beyond the edge of my talents.

Some of you who know how frustrating I found business school to be, will probably be surprised by how much I appreciate what I learned there. In undergrad I learned how to think, and in my first job I learned how to work hard. In business school, I learned how to teach myself. After business school, I now feel like a learning machine because I learned how to transform myself, use deep reflection to learn from my experiences (and from other people), and developed the courage to proactively do things that are very difficult (which are the experiences you learn the most from)**.

Finally, I started a job working for the City of Detroit that has been dynamic, inspiring, and challenging in the best way. I don't like to draw attention directly to my work on this blog (it's not about me, and I don't want my opinions to be construed as the administration's), but I will say this - my colleagues and I have been pushing very hard on projects related to public safety. I'm optimistic that our labor will start bearing fruit in 2016 and the results will speak for themselves.

A SUMMARY OF FAILURES

For better or worse, my failures*** this year were small in scope and large in quantity. It all boils down to one root-cause, committing to too much. Here are the most notable examples:

- I have been an advisor to my college fraternity for several years. I recently stepped down because I didn't put in the effort to help them at all. I'm in the process of resigning my position.

- I was working on planning some events with 3 high school friends. My commitment has been hot and cold for months.

- A close friend of mine had a emotionally taxing autumn. My friend is fine now and came out of it okay, but I was not sufficiently supportive during that time. Luckily, others were there for my friend to lean on.

- I can't even count how many times I had to reply to e-mails and texts, with something to the effect of, "Sorry, I've been behind on my e-mail for months, but I'd love to get together..."

Committing to too much has always been a struggle for me. I've already started taking steps to narrow my scope and stay focused.

A SUMMARY OF WHAT I'VE LEARNED

Over the course of the year, I've tried to keep my eyes and ears open. Here are some of the more impactful observations I've had.

Real Talk

Over the past few months, I've been asking a daily question which is usually of the "it made me stop and think" variety. Friends have shared some remarkably sincere responses. I've certainly learned a lot about what really matters to others. But most importantly, I've noticed that the conventional wisdom of "people are usually averse to putting themselves out there" isn't true. People crave honest, heartfelt interactions with other people. I've been shocked at how just providing a safe-enough forum and a sincere desire to listen makes a difference.

Being Present

For some time now, Robyn and I have enforced a rule that we don't check our phones at dinner time. It's taught me how hard it is to stay focused on the moment I'm in (my mind races to work, the future, anxieties, etc.). The broader lesson here is that you have to fundamentally approach "projects" with long time horizons (like marriage) differently than shorter ones.

For long projects, you have to be present and immerse your self in every second of it.

Longer projects tend to be harder, more complex, and more important. Because of that, you can't depend on quick fixes and short sprints of intensity to get them done. You have to show up every day, ready to work without cutting corners. To make it to the end of long projects, you have to find reward in the journey and not the outcome.

How To Change A Habit

I've been obsessed with changing habits as of late...because I'm getting married, because I'm getting older (and less healthy), and because my work requires it. I don't think there's one system to change habits that works for everyone. That said, there are three absolutely bedrock principles I've discovered when trying to change a habit.

First, you have to feel the consequences of your actions swiftly, ideally immediate after the action / decision occurs. Second, you have to find a way to make the new habit a ritual and build it into an existing habit. Third, changing habits doesn't just mean forming new habits, it also means killing old ones.

A SUMMARY OF WHAT'S NEXT

Because I'll be having so much life change in the next year (i.e., marriage and a dog, eventually) I don't intend on rocking the boat too much in other areas of my life. What I do plan to do, is continue to declutter my mind, my time, and the physical space around me. I've been cutting down on facebook and TV, and reading more. I've been trying to focus on changing no more than 3 habits at a time. I've been creating systems to reflect, refocus, and recharge. I've even been trying to downsize my t-shirt drawer. I'm not done with this yet and I intend to continue it into 2016.

What I do want to do is write more. I've been struggling to blog regularly and I intend to do so at least once a week in 2016. I also have been flirting with writing a book and it's time to get started. It'll be a memoir in two parts. Part I will be a series of observations about what is unprecedented about the times that we live in now. Part II will be a reflection on the sort of world I hope our grandchildren live in. I'm excited to share more as the year progresses.

Cheers to you and yours. Let's have a great year.

---

*Not many other business schools seem to have such a humble, thoughtful culture. Ross does more than others, and so does Haas.

**Being a learning machine starts with reading. The smartest people I know are all voracious readers. Shoutout to Dominik R., the most prolific reader I've ever met in person.

***I have lots of mistakes and failures. These were the ones that bothered me the most in 2015, namely because letting other people down is something that I really, really don't like to do.

Hustling Hard, Hustling Smart

Thinking through problems supercharges hustling.

In our town, you're either known as a talker or a hustler.

Talkers are the ones who have grand plans and spend hours in meetings figuring out what to do and getting "buy in". They're the ones getting everyone "on the same page" without actually creating something tangible.

Hustlers are the ones who think talk is cheap. They are the ones on the ground, getting it done. They are people of action and initiative. They're the dreamers who aren't satisfied just dreaming, they do, too.

In our town, you want to be known as a hustler not a talker, in my humble opinion. In Detroit, talk is cheap. Real Detroiters actually make things and make things happen. It's in our DNA.

I'd propose however, that there's one more category - thinkers. Thinkers are the ones who figure out the best way to go about doing something, so that the work actually results in something. It feels like a waste of time, but it's really an investment of time.

Thinking is a slow process, but when done well it allows teams to move much faster in the long run.

What's difficult for us thinker types is convincing people that thinking isn't a waste of time. Because for straight hustlers, thinking feels a lot like talking. It's on us to make thinking action-oriented instead of passive.

A National Policy For Working Fewer Hours

I don't believe a silver bullet which solves all our social problems exists. But finding a way to limit how much time we spending working is as close to a panacea as I've ever imagined.

I'd like to propose a hypothetical Federal law.

"For any hours worked beyond 40 hours per week (in total, across every employer and job held by the individual) the employee must be paid triple his or her normal hourly wage or effective hourly wage, if salaried."

Of course, in practice this would be difficult to pull off. But let's say it did (I know it's a stretch, but humor me). If so, it would likely discourage any employer from making their employees work more than 40 hours per week. And that - limiting our work hours in America - is an idea that's worth exploring.

To me, as much as we work in America has tremendous non-monetary opportunity costs. Here's a sample of what we could be doing if we worked fewer hours:

- Spending time with our children and families

- Exercising, sleeping, and other things to improve our health and motivation

- Participating in leisure activities which reduce stress and increase happiness

- Volunteering, and participating in civic life

- Learning or working on entrepreneurial projects

- Going to church or participating in some other spiritual development

- Shopping and participating in commercial activities

What I'm getting at is that there are lots of things we could be doing with our time that addresssocial ills we care about solving. Would kids do more homework if their parents were around more? Probably. Would we be less angry and violent if we had more time to rest and recharge? I'd think so. Would we have stronger communities if we felt like we actually had the time to talk with our neighbors? My guess is yes.

For those that care about economic arguments, I think penalizing companies for overworking employees would actually increase productivity and output. Working longer hours, particularly in white collar jobs, is a buffer that covers up bad management. If supervisors knew that they could no longer just force employees to work longer they probably would quickly learn to better manage their employees' time and only assign work that led to results. Applying a modest constraint on workers' time would cause the managers of companies to innovate their own management practices.

This is a side-note, but I also find the American tendency to wrap up our identities in our vocation to be damaging and unsustainable. If we literally weren't allowed to work so much, we would be more likely to define our lives in broader, healthier ways.

Of course, my crude, hypothetical policy of a psuedo-tax on hours worked beyond the first forty isn't the point. The point is that how much we work in America is probably damaging to our individual and collective welfare. Moreover, if we worked less, I would expect it to enhance welfare.

I don't believe silver bullets which solve all our social problems exist. But finding a way to limit how much time we spending working is as close to a panacea as I've ever imagined.

Ideas and Unlimited Shelf Space

Because ideas are basically free, it's getting harder to focus on the ones that really matter.

On the internet, it's basically free to create an idea and share it. In fact, that's what I'm doing now. In the old days, this wasn't the case. Ideas had to compete for shelf space to get in front of audiences. Now, ideas just have to compete for eyeballs.

There's a key difference here. When competing for shelf space, proprietors of ideas had to convince broadcast companies and publishers that they had ideas people wanted to hear. Moreover, if those broadcasters had a modicum of journalistic integrity, they could insist upon quality standards for themselves and for others.

Today, when idea-peddlers compete directly for eyeballs instead of shelf space, they can make money even if their ideas lack quality. After all, these peddlers can buy audiences with advertisements or with low-brow messages that appeal to humans' neanderthalic compulsions.

There are also many more ideas bombarding us on a daily basis than in previous decades. After all, If it's no longer costly to create ideas, two-bit hacks (like yours truly) say whatever they want whenever they want.

When ideas can become higher in quantity and lower in quality, it's harder to build momentum around a single (good) idea because there are so many lesser ideas to distract from it. What perplexes me is how to keep those more meritorious ideas around long enough so that they lead to action.

But maybe a way out of this cycle of distraction is getting back to to basics and propagating ideas the old-fashioned way, with authentic, in-person, interaction. And, by articulating ideas with such compelling quality, sincerity, and persistence that those who hear them can't help but talk about it with everyone they meet.

My Lingering Toothache

The slightest uncertainty of safety is what I find difficult about my racial identity - like a toothache that I have to just grow accustomed to

For my soon-to-be family-in-law, enjoying the lake life in Northern Michigan is a yearly ritual every fourth of July. During one of the evenings of this year's trip, we ate dinner at a local biker bar. Shortly before our dinner arrived, one of my siblings-in-law and I ventured to the far side of the bar to order a drink. At the time, we were both bearded.

While we were waiting, we overheard an over-served young man trying to charm a young woman. He, of course, was not particularly charming but was trying his best. As he was conversing with the woman, he said something which compared me to a member of ISIS and how he wouldn't be surprised if I did something to harm the patrons of the bar. He was obviously trying to use hyperbole to be funny.

I gave him a befuddled, "Are you serious?" jaw-hanging glance from across the bar. He was extremely embarrassed. When I ordered my drink, I bought him a round to demonstrate I didn't have lingering ill will toward him. This of course, made him feel more foolish.

I'm not interested in making preachy platitudes about racism, prejudice, or patriotism. Rather, I share this story to illustrate why I have a barely-noticeable, but persistent, anxiety in public places. I honestly don't know if someone's going to bother me because of my race (which in my case makes me arbitrarily different from others). What's worse, is that I don't know whether someone will hassle my family or friends because I happen to look like someone they think they should be afraid of.

The slightest uncertainty of safety is what I find difficult about my racial identity - like a toothache that I have to just grow accustomed to.

Money Shouldn't Be A Mental Model

In America, money isn't just a tool we use to buy things, it's a mental model that's hard coded into our brain from birth.

A clever way to understand a culture, I think, is to examine its commonly used phrases. In America, we have a remarkable amount of phrases about money. Here are a few examples:

"Money can't buy happiness."

"Penny wise and pound foolish."

"Making bank."

"Money doesn't grow on trees."

"You can't put a price on ______."

I don't think the most interesting observation here is that Americans care about money. It's that we think in terms of money. Put another way, when evaluating a complex situation, the first (and sometimes the only) thing we consider is it's price in dollars. In America, money isn't just a tool we use to buy things, it's a mental model that's hard coded into our brain from birth.

I think this is problematic because as individual humans we care about stuff, for reasons beyond their economic value. We care about how things make us feel and whether they adhere to our moral code, for example. Corporations have the luxury of thinking about the world exclusively through an economic lens because they don't have flesh, bones, and feelings.

People are more complex, which is why we ought to think of things in broader terms than just their price.

What's challenging is that there are many more frameworks which help us simply understand and evaluate economic value. I'm working on mental models to evaluate things not in terms of money, and if you have any thoughts on the topic I'd love to hear them.

Three Pre-Requisites for Intimacy

To have intimacy, I discovered at least three pre-requisites: accepting yourself, accepting love, and finding joy in sacrifice for others.

My last roommate, Divya, and I were talking about relationships a few weeks ago. During that conversation, I was vibing with her about three pre-requisites I discovered, to even be capable of an intimate, committed relationship.

First, I accepted my best self and quit trying to be my "ideal" self. No happy person can fulfill a false persona for an indefinite period of time. Eventually, with your partner, your true self will shine through. Consequently, it's practical to just be yourself from the beginning so there are no surprises.

Doing so is not easy, even though "being yourself" is proverbial wisdom. In society and culture we're surrounded by messages that talk about how to be an "ideal" lover, worker, and partner instead of ourselves. Fashion magazines, books (like Neil Strauss's "The Game"), blog posts on LinkedIn, etc. have checklists on how to be an ideal person to others. We're constantly nudged into being someone else, often subliminally. That makes it hard to "just be yourself."

Accepting my best self required me to stop trying to be the center of every social network, and constantly trying to be everyone's friend. It also required me to place less emphasis on being the best consultant at my company and considering myself a success only if I gained admission to the most prestigious graduate schools in the country.

Second, I allowed myself to feel deserving of love. After all, if you can't accept love it's basically impossible to give it. About 2 and a half years ago, everything in life was going well - I had a good salary, a good enough GMAT score, and lots of fun times with friends - but I felt guilty about it, especially about relationships. I didn't feel like I was worthy of being loved. In retrospect, pursuing extrinsic things (i.e., career, money, social status) was probably something I was doing so that I would feel accomplished enough to deserve love. I was in a terrible mental state and was driving myself to be crazier by the day.

I was lucky though, a few close friends and my family pulled me back and just gave me love without me even asking for it. They told me I was worthy of love (from other people and from God). They gave me books to read so that I could re-wire my brain. Everyone has a different process for realizing that they were worthy of being loved, and I was lucky to have a lot of support through it.

These two realizations have to come early on (or before) a relationship. My third realization came after starting a relationship with Robyn.

Third, I started to find joy in making sacrifices for my partner. Not just compromise or acceptance in sacrifice, but joy. Relationships (of any flavor) don't work without sacrifice. If they're not joyful, they aren't additive to the energy of the relationship, they're subtractive. Given the choice, why not be joyful about sacrifice? For Robyn and I, finding in joy in sacrifice was a virtuous sacrifice for our relationship.

Here's an example. I'm very messy about having clothes strewn about in my apartment. Robyn isn't ever upset with me about it, but she's definitely not amused by messy clothes. Knowing that she would rather have laundry taken care of neatly, I started to make an effort to put my clothes where they belong. This is something Robyn presumably appreciated so it made me happy. Because it made me happy, it became a habit, which made Robyn even more happy. Now, we're in an upward spiral of sacrifice and appreciation in more than just the realm of laundry. None of it would've happened, however, if either of us didn't find joy in the smallest of sacrifices.

To have intimacy, I discovered at least three pre-requisites: accepting yourself, accepting love, and finding joy in sacrifice for others.

The funny thing is, they have very little to do with "knowing what you want", "trying out lots of people", finding "the one" or other externally-focused cliches. Rather, these three truths I've discovered have to do entirely with changing yourself.

Business Modeling for Civic Enterprises

I'm proud to present an independent study project I completed at Ross which translates Allan Afuah's business model framework so that it can be used by public-sector executives.

In my last semester of business school, I completed an independent study research project under the direction of Professor Allan Afuah. Professor Afuah's research focuses on business modeling and business model innovation.

What I found is that business model frameworks are useful for private-sector executives, but have never been translated in a way that is useful for public-sector executives. The paper I wrote, translates Professor Afuah's framework for dissecting business models so that it's useful to leaders of "civic enterprises" in the public sector.

I hope you'll read the whole paper, but here's a very brief summary. Please let me know what you think, privately or in the comments.

The Business of Urban Growth - Executive Summary

Just like private enterprises, governments must create value for their customers (i.e., residents and taxpayers) to survive. Businesses have great tools, like business model frameworks, to help them think through their strategies for creating and capturing value. Civic enterprises, however, do not have a business model framework that is tailored to their executives' needs - until today.

Professor Allan Afuah has a great framework for articulating the business models for private enterprises, which I've translated to the civic context. Afuah's components of a business model are capabilities, value proposition, customer segments, revenue model, and growth model.

Here are the key takeaways from translating the business model framework for use by civic enterprises:

- Revenue Model - Revenues models are fixed by law, and therefore relatively simple. Crowdfunding could be a supplemental revenue model worth exploring.

- Growth Model - A good proxy for "growth" could be revenues and costs of a civic enterprise's budget. There are generally only four ways for civic enterprises to increase revenues: add population, add businesses, increase individuals' wages, and increase businesses' revenues. Therefore, all growth initiatives should directly impact at least one of those four growth levers.

- Market Segments - A civic enterprise's main segments are individuals and businesses, but additional segmentation would be useful so that cities could target their growth efforts on a limited number of segments.

- Value Proposition - There's clear research on what individuals (and businesses value), but it's not as simple as jobs and/or amenities. Perception of weather and social capital are a big determinant in what people value when they move.

- Capabilities - Civic enterprises need capabilities which fall into four categories: tangible assets, intangible assets, stakeholder networks, and management systems. There is no silver bullet, all types of capabilities are needed simultaneously.

I believe that the leaders of civic enterprises will have better results by using this translated business model framework when crafting their growth strategies.

Where Home Is

Life, in a way, has called me up to the major leagues. Starting on graduation day I finally felt that I was ready for it.

In retrospect, the most important thing I learned in Business School had nothing to do with mental models, financial statements, or innovative business strategy. Rather, it was discovering where home is.

Home is where Robyn is, where my family is, and amongst friends old and new. It's in Detroit and Rochester. It's at my grandmother's house in India. It's reading and learning. It's in serving others and taking risks. It's telling the truth and acting with honor and virtue. It's doing God's work. It's in adventures in and out of nature. It's in a notebook, a whiteboard, or a dance floor.

Home is in my vocation, not a job. It's in hard work, not in rent-seeking. It's not in headlines or awards - better results for customers and communities is reward enough. It's in friendship and fellowship, not "networking."

Now that I'm out of graduate school, the stakes in my life and at work are higher. I'm getting married in less than a year, and I'm taking a job that will be purposeful, but also very difficult. I have a frustrating debt of student loans, so I have to spend wisely every dollar I earn. Now, my actions actually have measurable consequences.

Life, in a way, has called me up to the major leagues. Starting on graduation day I finally felt that I was ready for it.

Today, a month after graduating from Ross, I feel one more emotion that's been eluding me for years: it's good to be home. Because of my transformative time in business school, and many hours of reflection, I finally know exactly where that is.

Reframing How I View My Job, Career

I used to dream about the job that I'd really like. Now, I've decided to view my career in an other-focused way.

I've begun thinking about my job and career differently; my perspective has evolved throughout and because of business school. I used to think about the job that I would like, even a job that I would be good at. A job that gave me the lifestyle, purpose, happiness, and pay I wanted. My "dream" job.

In retrospect, I consider that a self-centered view of my job and career.

But, I've learned in the past few years that true happiness comes from serving others, not yourself (the data is incontrovertible). That's helped me rethink how I make decisions about my job and career.

I figure, if happiness comes from being other-focused and how I view my career is self-focused, I probably won't be happy. As a result, I've decided to view my career in an other-focused way.

Now, instead of asking myself questions like, "What kind of job will I like?", I ask myself a different question that's more other-focused. I ask myself: "In my life, who am I excited to serve? Who's the customer I care about?" This reframing has changed how I've viewed my job after business school, a lot.

I think there are a lot of legitimate ways to answer this question, and what I've found is that it's most important is to be honest with yourself.

For example, I've chosen a job where I get to serve people in the City I live in. My customers are the current and future residents of the City of Detroit. But my "customer" is also my family. I chose a job that affords me a good (not lavish) lifestyle but allows me not to travel every week. It's a job that I'll likely have stress from, but it will be one that energizes me with optimism - I won't take negative emotion back to my family.

Maybe the customers you care about are other people in your company. Maybe it's the hungry or sick. Maybe it's CEOs. Maybe it's small businesses. I don't know, only you do. But what I'm saying, is that it's worth figuring out who you care about serving rather than figuring out what you like. If you're not excited to serve your "customer", you probably won't be happy.

Like most decisions, reframing the question I asked when considering a job / career change made a huge difference.

Who do educators really see as their customers?

It will be a game-changer if we can create an educational enterprise which truly treats students as the customer.

I’m not an educator, but let me share an insight about education that came to me while sitting in my business school class about the “Co-Creation of Value.” I’ll leave off a description of what the class is about, for now.

Think of a good teacher. I’m don’t even mean the very best teachers. I mean good ones, of which there are probably many. Those teachers, in my opinion, see their students as their customers. They create experiences which help their students learn. Moreover, they work with their students to co-create experiences which help them learn better. They adjust to students and do amazing things. They’re able to do this, because they interact with and communicate with their students every single day. There’s an ongoing feedback loop between good teachers and students. Incorporating that feedback into their teaching practice is indicative of a customer-oriented relationship.

When you look to other institutional stakeholders in schools (administrators, school board members, superintendents, policy makers, etc.) they don’t see students as their customers, the majority of the time. Of course, they claim too, but I would argue that their behavior doesn’t back up that claim*.

One piece of evidence is looking at who has the power to hold them accountable. Administrators, school board members, etc. aren’t held accountable for their jobs and performance by kids. They are held accountable by parents and voters (who are above the age of 18). Even if a student had strong feelings about those non-teacher stakeholders, they don’t have any easy mechanism to act upon those feelings. Sure, they could protest, or lobby their parents, but that’s an extremely indirect way to foster a change in their experience. Speaking, from personal experience, it’s also very hard.

The more indicative piece of evidence suggesting that non-teacher stakeholders don’t see students as their customers is how little time those stakeholders spend with students. Good administrators (of which there are some) spend time with students and incorporate their feedback, but from my observation that varies a lot across schools. The higher up the food chain you go, the less those stakeholders interact with students. This leads me to believe non-teacher stakeholders rarely, if ever, see students as their customers. They just don't spend enough time with them and really digging into understanding students' needs, directly.

This is a problem because ultimately students are the customer, they hold final power over whether they learn. So, because so many stakeholders don’t treat them like a customer, they don’t create the best solutions which help students learn.

If someone could truly create opportunities for students to be co-creative customers in their own learning and their educational experiences more broadly - beyond interactions with just individual teachers - I think it would be a game changing innovation. Why? Because customers, when co-created with, can give the firsthand feedback required to shape experiences to be better for them. Customers are the best advocates for their own needs.

A note on “good” teachers

A good friend of mine, Sam, pointed out that as a teacher he often hears that teachers treat students the least like customers and are the least likely to co-create with them. I’d personally chalk that up to all the testing and mandatory requirements that teachers have to follow. My guess is that good teachers have their hands tied when it comes to co-creating with students because if they don’t raise test scores and get through their requirements they are reprimanded.

So it seems that even if teachers appear to not be treating students like customers it’s probably because they’re being given directives by administrators, superintendents, school boards, policy makers etc.

Of course, there are probably “good” non-teacher educational stakeholders, too. I just see co-creative behavior much less by non-teachers.

* - For the record, I’m lucky to have had many good teachers and many good administrators while I was in school, especially as a student at Stoney Creek High School. So thank to all of those wonderful educators!

The Weaknesses We Shouldn't Ignore

In the workplace, it may make sense to focus our efforts on building strengths. But in life - and to be fully human - it also makes sense to work on on vanquishing the deepest sins of our character.

These days, it's fashionable to talk about building on one's strengths at work. After all, if we work primarily in teams, it doesn't make sense to try to be good at something that someone else is already much better at, comparatively. Rather, we're advised to build on our unique strengths - and not waste time on our flaws - so that we can increase our contributions in team settings and advance our careers more rapidly.

That may be true, but this weekend's thought-provoking piece by David Brooks reminded me of an equally important truth: we must work to improve the flaws in our character.

He says:

“Many of us are clearer on how to build an external career than on how to build inner character. But if you live for external achievement, years pass and the deepest parts of you go unexplored and unstructured. You lack a moral vocabulary. It is easy to slip into a self-satisfied moral mediocrity. You grade yourself on a forgiving curve. You figure as long as you are not obviously hurting anybody and people seem to like you, you must be O.K. But you live with an unconscious boredom, separated from the deepest meaning of life and the highest moral joys. ”

What that means to me that if we ignore the flaws in our character, we're ignoring our humanity and a responsibility to others to try to be good. Ignoring our character flaws is tantamount to allowing our core sins to fester and permeate to others.

My deepest sin is probably lust (broadly speaking) or maybe greed. That's not a "weakness" that I'm willing to ignore, even though building on strengths is what I'm "supposed" to do.

In the workplace, it may make sense to focus our efforts on building strengths. But in life - and to be fully human - it also makes sense to work on on vanquishing the deepest sins of our character.

Why I Reflect

It stymies me that reflection isn't a cornerstone of every learning enterprise on the planet

There are some things you can learn from a book or video - like how to make sushi, the history of Puerto Rico, or the varying methods for valuing a company. I'd argue that there are other things - like leading a team, comforting others, or making decisions in a crisis - that can only be discovered through experience. I'd argue further that the most important skills for having a good life can't be learned from a book.

It stymies me that reflection isn't a cornerstone of every learning enterprise on the planet.

Reflection is the key that unlocks tacit knowledge, the type of knowledge that can only be discovered through experience. Acquiring tacit knowledge is different than learning from a book because it takes more than memorization of the mind and body. Instead, it takes having new experiences, failing or succeeding, and internalizing what you learn. Tacit knowledge doesn't stick if you don't internalize it, and that internalization only happens through reflection.

Ironically, reflection is something that can be learned from a book or video and practiced. For a reason unknown to me, it just doesn't seem important enough to make part of the core body of explicit knowledge we learn in school. I think that's a monumental miss.