A Justification For Goodness

If we value freedom, we should also value goodness.

I don't think being a good person ought to require justification. It's almost part of the definition of something being good to not need justification.

But that's not particularly persuasive. So something I've been thinking about is why being a good person matters. In particular, I'm trying to think of an argument persuasive enough to affect the opinion of someone who doesn't already believe that being a good person matters.

Here's what I don't think is persuasive:

- "Because, God" - Theological guidance for moral behavior is a fine reason for being good, and I happen to be influenced by it. That said, there are a lot of people who range from ambivalent toward religious perspectives or downright resistant to them. Consequently, religious and theological arguments aren't sufficiently persuasive.

- "Because, it feels good" - To me, acting with goodness feels light, natural. It feels right. I feel good after doing the right thing, especially after a particularly difficult dilemma. But this isn't persuasive, because the spoils that can come from not doing good - and the power that comes with it - can also feel good.

- "Because, other people will respect me" - Sure, people whose respect is worth earning (in my humble opinion) will respect you for being a good person. But, if you switch your peer group you can get respect (cheaply) just as easily, so again - not persuasive.

Here's what I think is persuasive:

Let's consider a world where people generally act with goodness versus a world where people generally don't.

In both worlds, there is conflict. In both worlds, there is suffering (because even good people make mistakes). In both worlds, there is law and order (because we are sufficiently different from each other for misunderstandings to occur).

What I suspect would be different is the design of the governing institutions in the world where people generally don't act with goodness. There would have to be more laws, with steeper punishments, precisely because it can be expected that there are bad people. In that world, non-good people are not the exception, they are the norm.

As a result, there would have to be stronger components of law enforcement. There would have to be larger armies. The state would have to be strong, to prevent people from causing harm toward each other, more so than the world where goodness was the norm.

This is all to say that the state (or some other regulating entity) would amass power. Which is to say that those in cohoots with the state would also amass power. And as human history suggests when power is amassed by a select few, freedom becomes precarious.

So here's the most persuasive argument I can think of for being a good person. A society in which people act with goodness creates less of a need for strong, forceful institutions. Fewer strong, forceful institutions make it less likely that freedom will deteriorate. Because nearly everyone I can think of values a free society, we should be good and expect others to be good.

Goodness creates the space for free societies to exist.

The world keeps turning

My reflection on 2016 is that the world keeps going, with or without us.

This year started at 12:00:01 on January 1st and the world was turning. Two weeks later my father died.

And though I was devastated, in a way that felt violent and deliberate, it kept turning.

Then, we went skiing and the world kept turning. One of my close colleagues died. The world kept turning. We were married, I tried to elongate every moment and drop of joy in every last one of my nerve endings, because the world kept turning.

We celebrated weddings, births, and birthdays - near and far - and the world kept turning.

Some nights, when I was lucky, I talked to Pops in my dreams. And the world kept turning. When we visited my family in India, the world kept turning. The world was turning before, during, and after, I ran a half marathon.

When I made mistakes managing projects at work the world kept turning, too. Riley became part of our family and the world continued to turn just the same as when another colleague from work was murdered unexpectedly one night.

At Thanksgiving, Christmas, and every day between, before, and after- when we laughed, cried, stubbed toes, kissed, raised glasses, napped, walked along the river, hugged, voted, cooked, and read books. Even when we sat still and quietly the world turned.

In our new home, the world will turn.

I feel a strange mix of guilt and relief saying this, but when Papa died I felt for the first time it was really, honestly, possible that the world would stop spinning. But thanks to God, it didn't. As much as the only constant in life is change, I find it comforting that the world still turns - with or without us, and every living thing we've ever known - no matter what happens.

We don't have to concern ourselves with the Atlassian task of keeping the world turning, thank God. All we have to do is keep this world of ours a nice place for our children and grandchildren, and teach them to take care of it when we're gone.

If you're an audio person, you can also catch these posts (with a little extra discussion) by subscribing to my podcast via the iTunes store. Happy listening!

Iterating a life

Getting 1% better every day requires reflection and discipline.

This evening I came across a blog post about stoicism. The blog post boiled stoicism down to one sentence that a 5 year old child could understand. It came down to this - you cannot control what happens to you, you can only control how you respond.

Over the past few months, I've been starting a larger writing project and one of the two core questions I'm exploring is how to be a good man. As a result, I've necessarily been thinking about my own philosophy. Here's where I'm at:

Discovering how to be a good person (i.e., having good intentions and acting upon them) happens over time. The keys to getting 1% better every day are reflection and discipline, so focus on those two things instead of trying to be perfect.

I obviously have a lot of intellectual lifting to do here, but this is what my philosophy comes down to.

My Beliefs Haven't Changed

I'm not letting the election change my core beliefs about citizenship.

Before the 2016 Presidential election I'd like to think I acted with a specific set of values related to citizenship. Here's a summary of what I believed then.

I believed that community problems are best solved when all the impacted parties have a voice at the table. I believed that everyone was worthy of being listened to. I believed that issues should be debated vigorously with facts. I believed that I had a sacred duty to tell the truth. I believed that I had a responsibility to act on convictions, and protest the government when necessary. I believed that all political parties are on the same team, at the end of the day. I believed in treating others with respect, even if I didn't like them much.

I believed that violence is never acceptable. I believed that I should surround myself with a diversity of perspectives, including ones that don't conform to my worldview. I believed that I should argue (with civility) with people I disagree with. I believed in voting. I believed that complaining was not much more than cheap talk. I believed in thinking through the complexity and nuance of issues. I believed in changing my mind when the facts changed. And many more.

These are ideas I still believe in. It's going to take a lot more than one election to change my mind about the things I believed on Monday, November 7, 2016.

I've seen a lot of talk amongst the people I surround myself with (who tend to be progressives) and I suppose this is what I'm trying to say: I don't care who you are or who you voted for. As long as you're willing to exchange in a civil dialogue about issues, beliefs, and ideas, I'm willing to be part of it.

I have so many other ideas and frustrations about American politics at this moment, (about conservatives and progressives), but I think I'll leave it at that for now.

If you're an audio person, you can also catch these posts (with a little extra discussion) by subscribing to my podcast via the iTunes store. Happy listening!

Boiling my MBA down to four points

There are four general strategies to make a company more profitable.

The overarching point of an MBA is to try to figure out the answer to one question: How do you make a company more profitable? Being a fan of making complex things simple, here's my answer to that very simple question.

Basically, to make a company profitable you have to get better at one (or more) of these four things:

- Management

- Innovation

- Money

- External Environment

It's that simple.

All the strategies you can use to become more profitable - and by extension, everything you learn in business school - falls into one of those four categories. If you're running a company, and you want to become more profitable, all you have to do is brainstorm how you will tweak the four levers, prioritize your ideas, and start executing.

Apparently, management theories are more legitimate when you make them sound mystical, so I'll call this idea "Tambe's MIME Model." Before continuing, let me suggest that this model can apply to the public and social sectors as well, if you broaden the question from profitability to impact.

TAMBE'S MIME MODEL

Management is first lever you can tweak. This includes the management of people and other assets, like equipment, that people use to do their jobs. If you were to tweak this lever you'd figure out why your people weren't effective and then do something better. That might include improving the quality of managers and supervisors in the company, improving a process to increase output, or upgrading technology and equipment to something better.

Innovation is the second lever you can tweak. This includes introducing new products and services or improving existing offerings. If you were to tweak this lever, you'd put in the hard work of understanding customers' needs and pour resources into R&D to figure out a solution for those needs. Innovation need not be big - it could be as simple as improving one feature (e.g., remember when Apple added volume controls and a mic to its earbuds). Or, it could be as big as doing something the world has never seen before (e.g., creating the microchip).

Money is the third lever you can tweak. This includes cutting costs or improving the terms of financing. If you want to tweak this lever, you'd improve financial controls or find better ways of getting capital into the company. This is the sort of stuff people talk about when it comes to accounting, corporate finance, and improving the "bottom line."

External Environment is the fourth lever you can tweak. This includes increasing trust and awareness with customers or working to change the company's competitive landscape. If you want to tweak this lever you might do a marketing campaign, lobby for a more benevolent regulatory framework, or buy your competitors to reduce competition. Everything from lobbyists, to marketers, to M&A fall into this category.

I'd add that there's a dark side to using the MIME Model, because you can try to tweak these levers in an honest way or in a dishonest way. For example, when it comes to external environment, you could run a marketing campaign that truly informs consumers about the value of your products in a compelling way (think the Pure Michigan campaign). Or you could run a disinformation campaign that misleads the public (think the tobacco companies downplaying or outright lying about cigarettes causing cancer).

You could also try to lobby the heck out of an issue to prevent new, innovative entrants from entering your industry instead of upping your own company's game. You could threaten to fire people in order to increase productivity, or you could do the hard work of building a management culture that improves performance without fear tactics. If you ask me, appealing to the dark side of the MBA toolkit is cheating and not sustainable anyway.

Again, to summarize, there are four general ways to making a company more profitable: improving management, innovation, money, or the external environment.

In any case, I fully welcome your critiques on how to make this model more useful, especially from my fellow MBAs. After all, what's the point of spending a stupid amount of money on tuition if we can't distill what we've learned into something simple enough to be useful by us or by others?

For a great read that congealed my thoughts for this post, check out The Economist's special report on Superstar Companies.

If you're an audio person, you can also catch these posts (with a little extra discussion) by subscribing to my podcast via the iTunes store. Happy listening!

The freedom from meaningful work

I no longer expect work to be meaningful and I don't think you should either. Let me try to convince you.

I no longer expect work to be meaningful and I don't think you should either. Which you should be skeptical about, given that how I make a living could be considered "meaningful." Nonetheless, let me try to convince you.

I think of my mental health using a simple model, as a function of meaning and trauma. Basically, I try to do more things that fill up my heart (meaning) and do fewer things that are toxic (trauma). Perhaps that's a simplification, but it's honestly a good enough mental model.

Naturally, I then think about what's meaningful and what's traumatic. Here are some of those things. I don't claim to be a proxy for all humans, but I've found these to be consistent across people:

Things that are meaningful (aka things that fill up my heart)

- Serving others (or at least making their day)

- Accomplishing something challenging

- Learning something new

- Doing the right thing

- Expressing love and emotion

- Trying something that's never been done before

- Faith and spiritual exploration

Things that are traumatic (aka things that are toxic to mental and emotional health)

- Losing friends or loved ones

- Being yelled at

- Being shamed

- Being ostracized

- Being coerced

- Cutthroat competition

- Letting someone down

- Thinking you aren't good enough

Here's the point - the deeds that generate meaning or generate trauma can happen anywhere. Not just at work. Which is to say, meaning and trauma can be generated in any domain of life, whether it's at work, with family, when participating in public life, when with friends, anywhere. There's absolutely no reason we have to couple work and meaning.

Which is to say, to be a sane and happy person you don't have to generate meaning at work, because it can come from many other sources. In actuality, meaning and trauma need not have anything to do with work. They have everything to do with deeds, wherever they occur.

From there, I've thought about what I can control to keep the overall balance of meaning and trauma in my life at a healthy place. I've come to three truths:

- I have a lot of control of how meaningful and traumatic my life is outside of work

- I don't have much control of how meaningful my work is, but I do have some control over how traumatic it is

- If I put boundaries on my work, I can do things to recuperate from the trauma in life that is inevitable

So why not acknowledge work for what it is - important and useful drudgery - and generate meaning in our lives from the deeds that we have more control over?

If you're still not convinced, I can vibe with that. But I'd offer this advice from what I've learned. To borrow from David Foster Wallace - we're swimming through water (the culture of how organizations work) we don't even realize is there. To find more meaning at work most of the advice I see is tantamount to guiding people on how to be better swimmers (i.e., do these 10 things to find more meaning at work). That's crap.

What I think is better advice is acknowledging the water we're in and cleaning it up - changing the culture of how organizations work.

To be honest, I think we can generate a ton of meaning at work (even though I've argued against that strategy in this post) and that we should - especially given how much time we spend there. But I don't think that will ever happen without reimagining how organizations work.

The dominant "operating system" for how organizations function is hierarchal bureaucracy and cutthroat competition (think org charts, moving up the ladder, status meetings, and the like). The way that operation system is built structurally squashes meaning and propagates trauma. In other words, employees should expect that hierarchical bureaucracies, by design, will be traumatic and not-so-meaningful places to work. To add insult to injury, almost nobody likes hierarchal bureaucracy - customers, employees, or innovation-minded executives - and we still use it profusely.

The problem is, nobody has yet figured out an alternative to hierarchical bureaucracy. It's like the whole world is using Windows and nobody has invented Linux, MacOS, iOS, or Android yet. Maybe someone has, but the word hasn't yet gotten out to the masses.

And that, my friends, is why I'm on a mission to imagine alternatives to hierarchical bureaucracy and experiment with new ideas at work at every opportunity I can.

If you're an audio person, you can also catch these posts (with a little extra discussion) by subscribing to my podcast via the iTunes store. Happy listening!

Management is simple

If you can convince others to advance a common interest more often than they advance their own interests, you've succeeded as a manager. That's it.

Don't let pundits, the mess-load of half-rate leadership books, overpriced management consultants, or blogging MBA graduates fool you - management is simple. It's not easy, but it is simple. It's taken me twenty years to reach this insight but here it is. Management comes down to this:

Management is a craft of shared sacrifice. If you can convince others to advance a common interest more often than they advance their own interests, you've succeeded as a manager. If you haven't done that, you've failed. It's just that simple.

If you had to buy-off, intimidate, or otherwise coerce someone to advance a common interest, you're a manager - but a pretty bad one. If you've done it without coercion, you're a pretty good manager. If you've convinced others to advance a common interest, but that common interest is harmful to society in some way, you're not only not a manager, you're also a scoundrel.

All those other things that you can learn about management, leadership, organizational strategy, and such from books and leadership coursework still apply. Yes, you have to be vulnerable. Yes, you have to clearly define roles and responsibilities. Yes, you have to have integrity. Yes, you have to inspire. Yes, you have to have accountability and control systems. Yes, aligning incentives matters. But following those rules is not a formula for being an effective manager.

At the end of the day, the result that matters is if a group reaches a place of shared sacrifice. If you can do that, everything else falls into place relatively easily. Getting others to advance a common interest more often than they advance their own interest is the only rule you really need to know.

If anyone else has a better sentence describing the essence of management, I'm all ears and eager to learn from you.

If you're an audio person, you can also catch these posts (with a little extra discussion) by subscribing to my podcast via the iTunes store. Happy listening!

Putting Family First

Putting family first is not settling. It's actually quite the opposite.

For a long time, even though I said "family comes first" and I tried to live by that principle, in my heart of hearts I thought it was wussing out. You know, something that people who fell short on their careers and ambition said. I thought making family the center of one's life, though virtuous, was in a way, the easy way out.

As it turns out, I was epically wrong about that. Putting family first is the hardest possible path. Luckily, it's also the most rewarding.

Putting family first - which right now for me means investing in my marriage - takes everything I've got, every day. First, it takes an enormous amount of time. And by time, I mean time with intense focus, energy, and undivided attention. From what I've heard, this gets even harder when kids enter the picture.

Second, it takes an incredible amount of sacrifice. Sure, some days you lean on your partner and family more than they lean on you. But for it to work in the long run, everyone has to give more than they get - and find pleasure in it. Put simply, "the team, the team, the team."

Finally, it takes an incredible amount of trust, faith, and vulnerability. Even on the easy days you have to dig deep and keep your mind and soul open to love - and that's taxing, scary work. More than that, you have to trust that your partner is going to do the same.

Putting family first is so hard, in fact, it's essential that we all help each other build our marriages, families, and by extension our collective community. Luckily, all this is so fulfilling it makes the hard, hard work feel easy in retrospect.

Don't get me wrong, my most difficult days at work are really challenging, and require a considerable amount of cleverness, plus a lot of hard work. But nothing I do for my job is as audacious as building a marriage and family. A career is a series of goals that you must chase with dogged persistence. A family is a series of shared dreams you bring to life with devotion and unconditional love. That puts family in an entirely different league.

When I was a younger man, I don't know why a focus on family made me feel inferior, soft, or professionally inadequate. I don't think any of us should feel that way, because building a marriage and family is not an easy path. Putting family first is not settling. It's actually quite the opposite.

I need your help to tell my story

I need your help. I need you to tell my story to people who will never hear it otherwise.

I need your help. I need you to tell my story to people who will never hear it otherwise.

I need you to tell them that brown people are peaceful, just like non-brown people. I need you to tell them that people who are good at math can be good at things other than engineering and IT. I need you to tell them that people who choose to be goofy aren't pushovers. I need you to tell them men who bake bread on the weekends, learned ballet, or watch an inordinate amount of Star Trek are just as capable of being men than those who constantly talk about sports. I need you to tell them that those who don't humblebrag about their credentials are as talented as those who do (maybe more).

More than anything, I need you to tell them this: don't believe TV or the Internet is a representative sample of reality. Regardless of the identify of mine you consider: race, religion, size and shape, attitude, political beliefs, or level & disciplines of education, what you see on TV or the internet is only a caricature of that identity.

I didn't even know it until yesterday, but the Brexit and rise of Trump Republicanism have made me fearful. Not only because of how much of a train wreck a Trump presidency would be, but because of what his rise indicates. When I see Trump winning primary after primary, it signals to me that people believe those caricatures they see on TV about categories of people they've never met. I fear that belief in those falsehoods will affect how people treat me and eventually turn to violence, because that's what's happened throughout history.

The best way to combat those beliefs are to expose folks to categories of people they've never met. But no matter how many dinner parties we all throw, that's not enough because there are probably lots of people who will never willingly expose themselves to new things.

Which is why I need your help. I need your help to set the record straight about me and others who have identities that are made into caricatures on TV and the internet. I need you to tell my story to those who will never hear it otherwise. I am probably already doing the same for you.

If you're an audio person, you can also catch these posts (with a little extra discussion) by subscribing to my podcast via the iTunes store. Happy listening!

A Celebration of Being Outside

I was twenty-two years old when i was truly "outside" for the first time. Since then, the outdoors have brought me great joy.

For the majority of my childhood, I lived inside. I was a bookish kid who went to dance classes, swim team practices, school, and not much else. Later, I started to participate in sports like football, tennis, and track, but that's not exactly being outside, either. Nothing about those sports requires you to be outdoors.

I never appreciated really "being outside" until I was twenty-two years old. Two of my close friends - Aaron and Jeff - took me on an overnight camping and hiking trip to Giant Mountain in the Adirondacks, near Lake Placid, New York. They were both seasoned outdoorsmen and they showed me the ropes. It was the first time I was truly "outside."

They helped me buy equipment and shared some of their equipment with me. We applied insect repellent and ate foods that were closer to rations than a meal. I had boots that over the course of two days, actually got dirty. We boiled water to make lunch on a windy mountaintop. We were caught in the rain. We ventured far enough away from automobiles, that we couldn't hear road noise. We traded stories about the trail and about our lives. By the end, I was anointed a trail name - "Bucket List."

Experiencing nature is now one of the things in this world that brings me the most joy. Since my first trip with Aaron and Jeff, I've now been to almost a dozen state or national parks across the world. My wife and I even spent part of our honeymoon at Mammoth Cave National Park in Kentucky. I'm now experienced enough to help others experience the outdoors. It is a great honor and duty, I think, to be a person that introduces someone else to the glorious natural treasures we have in America.

Our country and world are so blessed to have tremendous majesty and natural beauty. And experiences in nature leave you feeling so connected not just to the earth, but to all those have traveled trails before you - it's a damn near religious experience. Once you experience the outdoors in such a meaningful way, it's hard not to take that appreciation to other parts of life - whether it's in your own neighborhood (Detroiters - Belle Isle!) or to the ballot box.

This year marks the 100th anniversary of the National Park Service - it's a celebration of being outside. Whether it's a park, nature reserve, or historic landmark you'll be glad you visited - take a trip! Not only is it wonderful, it can be a very cheap vacation. The Park Service has actually really upped its game and it's never been easier to plan a trip, just head to findyourpark.com or recreation.gov.

If you're an audio person, you can also catch these posts (with a little extra discussion) by subscribing to my podcast via the iTunes store. Happy listening!

My $3 Trillion Mission

The potential gains from choosing an alternative to bureaucracy are enormous. It's my mission to imagine those alternatives and bring them to life.

I don't like bureaucracy. As an employee it's oppressive and as a manager it's stifling and frustrating. Perhaps there's a time and place for bureaucracy - when control needs to be the top priority of an organization - but in the vast majority of situations, bureaucracy doesn't make sense.

What Gary Hamel and Michele Zanini figured out is that bureaucracy is also expensive. In a paper they published, they estimated that bureaucracy costs the US economy $3 Trillion dollars a year. For businesses, getting rid of bureaucratic management means more profits. For cities and governments, getting rid of bureaucratic management means more jobs - assuming that gains are reinvested in job creation. For people, getting rid of bureaucratic management means better and cheaper products and services.

The potential gains from choosing an alternative management style to bureaucracy are enormous. It's my mission to imagine those alternatives and bring them to life.

For me, the stakes are higher than just financial gains. I think about how so much of the reason people hate their jobs is because of how their companies are managed. People take that stress home to their families and it has real effects on their well-being. I think about how bureaucracy wastes so much of our country's talent. We could have so many more life-changing inventions and innovations if organizations used management styles that unleashed people's talent instead of letting bureaucratic management degrade their talent.

We can choose alternatives to bureaucracy, and our world would be better off if we did. I mentioned before that it's my mission to imagine alternatives to bureaucracy and bring them to life. I'm not the only one, there are management thinkers, company executives, and other influential people who are going to the mat for this fight.

But it's not just powerful people who can make a difference in this. Imagine if each one of us did something different on our own teams to make them less bureaucratic. Each one of us can challenge the status quo in our own organizations, whether it's by doing something to communicate across silos, or by giving our front-line colleagues the authority to make just one decision currently made by a manager.

We can all be a part of bringing alternatives to bureaucracy to life. And we should.

Exciting news, I'm starting to podcast my blog posts! You can listen to episodes here (below) or subscribe to the podcast in the iTunes store.

Life Is Built In The Off-season

Getting through hard times is much easier if you cultivate relationships and restorative habits during the good times.

The past few months have been the hardest "season" of life that I've ever had. I lost my father, I've had very rewarding but very high-pressure projects at work, I've had to help plan a wedding, and I've had to learn to live with the steam-rolling weight of student loan debt.

Because today was a particularly difficult day, I started to reflect on the most important lessons I've learned this year. After all, what good is a hard season in life if you can't learn from it? So I thought, "How'd I get through this?"

It didn't take me long to realize that the only reason I got through this season was because of the outpouring of support from loved ones that I've built relationships with over years and decades. Even people I barely know sent me nuggets of wisdom and comfort after my father died.

Moreover, I've been able to lean on regular rituals like morning gratitudes, alternating grocery shopping weeks with Robyn, or attending an at-home brunch hosted by two dear friends every second Saturday of the month. Hell, even the consistency of eating exactly 5 spoonfuls of yogurt with granola cereal every morning helps keep me sane.

I could go on. But here's the point.

Life is built in the off-season, when things are going smoothly and there's not a crisis afoot. Building up relationships and disciplined routines are the guardrails that keep you afloat during difficult times. Habits and relationships are an inoculation against adversity, and they are most easily built during the calm times between storms.

So, if you asked me, "how did you deal with the past few, very hard, months?" I'd tell you that you were asking the wrong question. The better question would be to ask what I did in the off-season to prepare.

How To Actually Build A Culture - What I've Learned

Don't mimic a different organization's culture, evolve to one based on your business environment.

Most companies I’ve come across are copycats. Their founders and executives look at how other companies do business and mimic the work environments (a composition of a company's habits, rituals, and practices) they like. In effect, they try to copy the culture of organizations they’ve seen before. On it's face, this is a fool's errand because most people haven't been in a high-functioning organization or team to begin with.

Even worse, it's reckless to mimic a different company's work environment, even if it is high-functioning. Why? Because those practices might not work well in a different business environment. Instead, the curators of a company’s culture – which are most often its founders and executives – should evolve their company’s work environment to fit the context in which they operate.

Animals and plants have been doing this for centuries. Camels and cacti, for example, have evolved to deal with water scarcity because they live in the desert. Bears have lots of fur and hibernate in the winter because that's what they need to survive in a colder climate. Animals and plants evolve to their habitat.

Companies, or even individual teams, should do what animals do – evolve their work environments to fit their habitat. Just like it doesn’t make sense for a camel to try to mimic a bear, it doesn’t make sense for a company in one “habitat” to mimic the culture of a company with a different business environment.

What's My Company or Team's Habitat?

I’ve found that the answers to two questions give reasonable insight to what a company’s “habitat” is and what that habitat requires of its work environment. After all, if you’re in a position to shape the culture of a company or team, it’s hard to do that without what your business environment requires. Here are the two questions:

What do your customers reward – execution or innovation?

What is the operating context in your market niche – simple & stable or complex & dynamic?

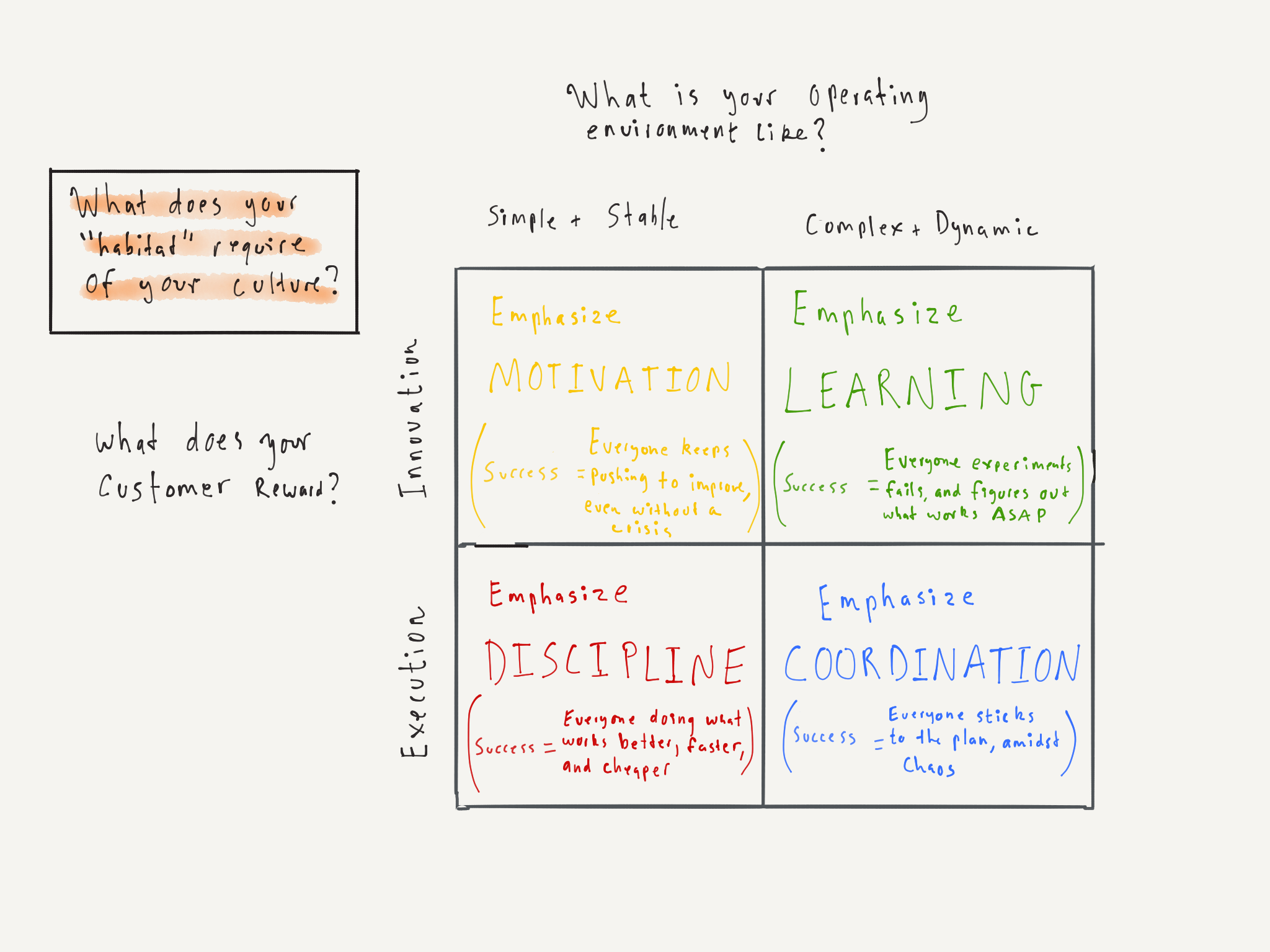

These two questions yield 4 basic “habitats” that each require a company or team’s work environment to emphasize different attributes - Coordination, Discipline, Motivation, or Learning:

(For help on how to determine your company or team’s habitat, click to this supplementary post).

How to Evolve A Culture

Correctly identifying your company or team’s habitat is one challenge, and evolving its culture to fit that habitat is quite another. I think the way to do this is choosing something – a moment in the day, an interaction, an artifact – and experimenting with it. Some colleagues and I put pen to paper on this concept in Work Environment Redesign.

I’d recommend experimenting with something small and mundane that’s done a certain way because “it’s the way we’ve always done it.” My favorite example is reimagining standing meetings. Here’s how the agenda of a standing team meeting could look for companies and teams in different habitats.

Lot's of little things can be evolved to fit a company's habitat - annual reports, branding, how customers are greeted, physical space, how recruits are interviewed, etc. Even if you only experiment with only one or two aspects of your work environment at a time, you’d be surprised how much your company or team’s culture can evolve even in a few months.

One more nuance I'd like to point out is that this model implies that a company's culture shouldn't be permanent. If a company's business environment changes, so should its work environment.

If you have stories or experiences to share with others about evolving your company or team’s work environment and culture – I’d love to hear about them in the comments (or a guest post)!

Supplement to "How To Actually Build A Culture - What I've Learned"

A supplement to my post "How To Actually Build A Culture - What I've Learned".

This post is a supplement to "How To Actually Build A Culture - What I've Learned"

Determining your company or team’s habitat is not a trivial pursuit. Ask yourself these two questions:

- What do your customers reward – execution or innovation?

- What is your operating environment in your market niche - simple & stable or complex & dynamic?

Of course, answering these questions is not trivial either. Here are some other guiding questions to help you come up with the right answers:

What do your customers reward – execution or innovation?

- Is your customer always going to what’s new?

- Are your customers fixated on price or quality?

- How often do your customers expect new products and services?

- Do you have a fan-base of early adopters in your market niche?

- Do customers know what they like and demand it?

- Are customers dissatisfied or bored with what companies in your niche offer?

What is the operating context in your market niche – simple & stable or complex & dynamic?

- Is your company or team divided into a lot of geographies or divisions?

- Do you interact with a lot of partners?

- Is there a new regulation that’s causing everyone to change?

- Is there a new technology that’s disrupting the status quo?

- Do customers have a lot of power when they’re making choices?

- Are there a lot of new entrants to your market niche?

Management Is A Technology That Needs Upgrading

At work, we've abandoned typewriters and horses & buggies, but we still use management practices that are nearly a century old.

So much of how we operate at work is settled on because that's how we've always done it. In the past few weeks I've had a heavy hand in shaping a team, which is why I've been reflecting on the topic. I don't yet know the best way to build a team, but what I do know is that in most cases, conventional wisdom is totally wack.

Rather than prescribing an "ideal" way to operate a team, I think different situations require teams with radically different operating systems (e.g., the way a team focused on responding to a natural disaster should work and feel is likely much different than how a team staging a play should work and feel). That said, corporate environments tend to have a few standard features, that don't often make sense for today's operating environment. Here are a few examples:

ORG CHARTS

Most teams I've been on are obsessed with organization charts, even though they don't say much. Org charts, after all, leave out mission / purpose, the roles on the team, the relationship across organizational units, and norms on how decisions are made. People seem to make them just because they think they're supposed to.

In my experience, org charts are helpful only for identifying who gets to resolve disputes during a turf war. I'd add, that org charts are a calling card of a hierarchical bureaucracy (a form of organization designed to avoid change), which is precisely the opposite of what today's operating environment requires. If you have a manager that insists on having an organization chart for the sake only knowing "who reports to who" - that's trouble.

STATUS REPORTS / STATUS MEETINGS

Most status meetings I've been to are a colossal waste of time. Usually managers have them for the sole purpose of making it easier to report to their boss, who is invariably an executive. If a team's manager is having a meeting for the sole purpose of checking on work, they are probably a terrible manager - a manager should know that already.

I'm not suggesting that teams shouldn't meet. What I am suggesting is that they mostly likely need to meet for reasons other than reporting on progress - like coordinating complex tasks, raising issues, or sharing learnings. If you have a manager that holds a "status meeting" and the manager does most of the talking, or it's basically a sequence of 1-1 interactions between the manager and each direct report - that's trouble.

INTERNS / JUNIOR STAFFERS

Lots of teams I've been on, treat interns and / or junior staffers like garbage. This is not only frustrating to the intern and a crummy thing to do to another human, it's a waste of talent.

To me, how teams treat the lowest colleague on the totem pole is a measure of that team's morality and their effectiveness. After all, if the way a manager under-utilized someone's talent solely because they're the youngest, newest, or lowest paid - it probably means they're not good at utilizing anyone's talent. If you're on a team that treats interns poorly - that's trouble.

I don't mean this post, entirely, to rib poorly run teams or incompetent managers. I've actually been lucky to be on more than my fair share of highly effective teams with effective managers. What I'm suggesting is much more radical. I'm suggesting that everything about how today's teams are built and how they operate should be questioned. So much of how organizations operate today is solely because "we've always done it that way".

To me, management is just like a technology. Computers are a technology for manipulating information. Rockets are a technology for traveling to space. Management, similarly, is a technology for coordinating a group of people toward a common goal.

Most organizations no longer use typewriters, horses & buggies, or quills & ink. Consequently, I think it's absolutely ludicrous that most organizations still use management practices that were pioneered almost a century ago. It's time to think more deeply about the technology of management.

The way I think of building teams and organizations is how I understand genes. In a living organism, some genes control eye color, some control height, and some control sex. Depending on how those genes are combined, you get a different kind of organism.

I think of teams the same way. Organizations have "genes" too, but in management we call them "norms". Some norms control size of the team, some control communication practices, some control conflict resolution, and some control how feedback is delivered, and so on. Depending on the goal and context, different teams need different genes.

Most managers act as if the norms of teams can't be changed - they just take what they've seen before and replicate it. That's a tragic mistake that's usually bad for the company, bad for the team, and bad for customers.

How To Solve A Problem

I put together this mind map on how I've come to approach problem solving. Credit goes to the many mentors I've had in the enterprises of problem solving and innovation.

How do you solve problems? What's your critique of my approach?

How To Solve A Problem

It Is Time To Build A Boat

Many generations of my ancestors have been preparing me for this moment.

The first thing I thought about when sitting in Culebra, Puerto Rico on the most beautiful beach I've ever seen, and staring out at the ocean was that "Papa would've loved this."

After all, my father had the heart of an explorer and loved natural beauty. I quietly dreamed about surprising him with plans of a road trip tour of the American West - National Parks and all - someday soon, which we'll never get to do now. But regardless of that, he would've certainly been pleased with the breeze, sunshine, and the bluest blue water I've ever seen with my own eyes. That was my first thought.

Then the second thought that came to mind, was, "How the hell did I get lucky enough to get here?"

You see, I'm the only child of two Indian immigrants who grew up pretty poor and really poor. When my parents arrived in this country, they were a bit older than me and they were still struggling, much more than I am now. And there I was, sitting on this remarkable beach, with some of my oldest friends for a weekend jaunt, soaking in the sort of scenery my father dreamed of - all before hitting my 29th birthday.

I got there because I've been lucky enough to stand on the shoulders of giants, benefitting from the accumulated hard work and integrity of probably a dozen generations before me. My ancestors, most notably my parents, brought me to the precipice of where I think damn near every person hopes their descendants will reach someday - on the cusp of making it.

I realized this weekend that I was born at the inflection point of a hockey stick graph. For generations my family has been moving along the shaft of the hockey stick, with things getting slowly, linearly better from generation to generation. And after one last big push from my parents, I'm looking out at a chance to end my family's incremental growth. I'm at the inflection point right before the blade of the hockey stick when things get exponential. I'm right here, at the point of making it that my ancestors - most of all my father - have been working toward for generations.

But I don't even know what "making it" means, exactly. Does it mean becoming wealthy? Does it mean being able to see the world and having opportunities leisure? Does it mean being able to make an outsized impact on the world and move humanity forward in a tangible way? Does it mean doing something which brings honor to my family's name? Does it mean laying a foundation so my kids can have an outsized impact someday? Does it mean living without the shackles of want or oppression? Does it mean having a happy life surrounded by the love of family and friends? Does it mean becoming one with God?

I don't think I'm alone in feeling this way, especially among the children of immigrants. In many ways, we live an easy life. More importantly, we live in a time where I'd guess than many more people than ever before are being born at the inflection point of a hockey stick.

So I am confused about where to go from here. But only confused and not afraid, because my parents taught me well and are with me always (just as all my ancestors are). I just wish I could say, "thanks, Pops." I understand the magnitude of his sacrifice and his greatness now more than ever. He literally and figuratively brought me to the water's edge.

And I suppose that if I'm at the water's edge, it is time for me to look up to the sky for guidance from my father and all my ancestors before me and build a boat.

The ESPN Effect

To me it feels wrong to trust ESPN more than I trust the channels which cover hard news. But it's not surprising.

In my book, ESPN is the most trustworthy news source on television. I've especially noticed this when catching gulps of election-cycle news coverage on traditional news channels in public places like airports or restaurants.

To me it feels wrong to trust ESPN (or other sports media) more than I trust the channels which cover hard news. But it's not surprising.

During sports press conferences, the players and coaches answer questions candidly and admit mistakes. Interviewees on traditional news channels have this arrogant way of misdirecting their answers to sincere questions and reek of poll-tested sound bytes.

In the sports media, the vast majority of stories focus on the "scoreboard" in some way - who's winning the current game, whose offseason acquisitions make them likely to win, and which players & coaches are likely to propel their teams to championships. In sports, to focus media coverage on topics related to winning and losing is relevant and substantive. In my opinion, sports media doesn’t venture too much into locker room gossip (which in sports is a rather frivolous thing to discuss).

Traditional news seems so bush league compared to that. In covering the presidential race, for example, I feel like I hear more about polling numbers and fundraising totals than I do about actual issues. The coverage feels riddled with talk about inside baseball between politicos rather than something substantive.

Finally, sports media tells great stories. ESPN, for example, continues to do amazing documentary work in the 30 for 30 series. Heck, during the Super Bowl I probably enjoy the montages and season-recapping human interest stories more than the actual game. Sports stories have this palpable earnestness and seem to let the truth drive where the story goes. This is unlike traditional news in which the journalists - at least to me - always feels like they are subversively trying to bend the story to their own worldview.

I think it's also worth noting how caring discussions about sports can be. I've heard men in the barbershop passionately argue about sports with remarkable civility. Nobody ever insults their buddy, nor do people hold their opinions as sacred. People actually listen to each other. When talking about sports, I've actually seen people change their minds when presented with better evidence.

Of course, these days, "civil" is one of the last words I'd use to describe discourse stemming from traditional news coverage. I can't help but think the quality of the media companies, and how they approach their work, makes a difference. I can't help but think that because ESPN (and other sports media organizations) approaches its work with integrity and thoughtfulness, it leads to greater civility when everyday people hang out together and talk about sports.

Free Time Is Worth Protecting

48 hours per week is a comically small amount of time to really live.

On February 15, the daily question I asked on Facebook was, "What's one way you're trying to change this year?" I replied:

"Focus more on fewer responsibilities."

I've said this in the past, and failed to focus on fewer responsibilities. This time around, I decided to write down all the responsibilities I have and how much time I spend on them, just to see what I could cut down on. Here's a rough summary of what I budgeted for:

- Sleep - 8 hours / day

- Work - 10.5 hours / weekday (or more) and sometimes more on weekends

- Eating / Cleaning Dishes and General Life Maintenance - 1.5 hours / day

Let me stop there for a second. Those three activities are essential, I can't realistically stop working, sleeping, or eating. Here's what's left:

168 hours / week (24 hours a day x 7 days a week)

- Sleep (56 hours / week)

- Work (52.5 hours / week, at least)

- Life Maintenance (11.5 hours / week)

= 48 hours left per week after accounting for non-negotiable activities

When I plotted this out, I was flabbergasted. Borrowing from the concept of disposable income in personal finance, my "disposable time" every week is only 48 hours.

Which is to say, everything non-essential to staying alive has to fit within 47 hours every week. That includes spending time with Robyn, family, friends and eventually kids. That includes reading and exercising. That includes personal correspondence and all side projects.

48 hours per week is a comically small amount of time to do the things most people believe make life worth living. I'd encourage you to do a similar audit of your own responsibilities. If you're anything like me, you'll be much more protective of your time and attention after counting out the hours.

A Case For Quitting Your Career

Why aren't there more smart people in the industries that matter the most?

In the middle of January, I found myself in the most unexpected of places - the intensive care unit waiting room of a hospital in Philadelphia. My father was very ill and my mind was (obviously) racing. I don't know exactly why - maybe my reaction to the stress was to distract myself by thinking about something else - but while I was there I marveled at the medical devices being used as part of his treatment. And I don't know why, but I started to ask myself, "why do so few smart people I know want to work for medical device companies?"

In addition to reflecting on this myself, I put a few questions related to this topic onto facebook and soaked up what people wrote. Anecdotally, it seems as if there's a mismatch of talent in our country. A disproportionately small amount of the world's bright talents tend to enter industries which have a disproportionately high impact on human society.

But why?

After reflecting on some of the reasons which might be deterring more smart people from taking their talents to an area of greater purpose, here's my no-pulled-punches, call to action to my smart friends: you can quit your career. Join those of us on wacky, non-standard paths.

Taking a pay cut is not that bad

I'll be the first to admit that I grumble about my student loan debt all the time. I'll also readily admit that I'm very lucky to make a good living - my pocketbook is modest, but not hurting. That said though, I took a pretty hefty pay cut when I started my current job. But to all my MBA / Law friends there who feel conflicted about those strategy consulting, I-banking, corporate, big law jobs...don't worry. It's not that bad to live on a budget, especially if your budget is still substantially higher than the income of the average American family. The pay cut is nothing to be afraid of. And besides, a high-paying job or glitzy perks are usually a good indicator that the company is making up for something else about the job that really sucks.

You're not actually learning that much more

Prestigious firms like to talk about how much you learn while working for them. I think that's misleading. First of all, people in smaller or scrappier organizations tend to learn a lot, very quickly because they're thrust with more responsibility. Second of all, I think how much you learn at work has much more to do with your own disposition than the company. People who take risks, work hard, and have a learning mindset learn wherever they go. If you need a perfect company culture to learn, you'd probably get just as much of a boost in learning by staying put and changing your attitude.

You don't need a name on your resume to prove that you've made it

One of the things I've learned is that someone's resume or educational pedigree isn't a good indicator of who I'd pick to be on my team. As many folks who responded to my facebook questions pointed out - there are many kind of intelligence and there are smart people all over the place...that didn't go to elite schools or work for top firms. Don't think you need to work for a so-called prestigious firm to "make it." At the end of the day, your deeds and results prove your character and your talent. Not a line on a resume.

Doing hard stuff is not that scary

I wouldn't have admitted this at the time, but working at a cushy company was really easy, stress-free, work. At the end of the day, my actions didn't have measurable consequences on real people. It's certainly hard to work in gnarly, complex, environments fraught with problems - which tends to be the case in consequential industries. My father said, "There are many problems, but there are also many solutions." I think that wisdom applies here, too.

---

Of course I realize that my examples are hyperbolic. And of course, I'm not suggesting that everyone quit their jobs, move to Portland, and become sustainable food-truck owners, inner-city teachers, design-thinking consultants, non-profit staffers, or anything else that fits this rosy picture of a impact-driven career. I'm also not trying to suggest that the world doesn't need bankers, consultants, corporate lawyers, or people to start cutsy billion-dollar tech companies that don't really serve anyone but the affluent.

What I am saying, though, is that there are too many really bright people (at least among people I know) that are in jobs that are an insult to their talent and that the world would probably be better off if those people did something more consequential.

I don't normally soapbox (anymore) in blog posts and I'm normally not so poignant. I get that, and I get it if anyone reading this feels taken aback or offended by this post. I sincerely apologize for that.

But here's what really gets me, and why I am so vigorous in my passion for this idea. It goes back to when I was in the ICU in Pennsylvania, after spending the last few hours of my father's life at his bedside.

I kept thinking, If more of the world's smartest people chose to build medical devices instead of being consultants and investment bankers, would my papa still be with us?