Developing courage in the new year

Courage is the king of all virtues. Developing it on purpose can make a huge impact on our own lives and on the people we seek to serve.

As it turns out, developing courage in ourselves is not so easy. We have to learn it by practicing it. There’s no YouTube video (that I’ve found at least) that we just have to watch once and suddenly become courageous. Reflection and introspection is the best method I’ve found so far (and that’s not particularly easy, either).

In lieu of a New Year’s resolution like running a marathon or reading 20 books, I’ve opted to commit to a practice which I hope helps me to cultivate courage.

In hopes that it’s helpful, here It is:

First thing in the morning, answer these two questions in notebook, quickly:

What do I think will be one of the hardest things I have to do today?

How do I intend to act in that situation?

Last thing at night, answer these two questions in notebook:

What was actually the hardest thing I had to do today? Why was it hard?

What should I do differently next time?

I’ve been on the wagon for about 6 days now. Here’s what I’ve learned so far:

Even considering what’s going to be hard, helps me to have a plan. That makes me feel more confident and courageous in the moment

Debriefing and learning from the hard stuff yields benefit quickly, sometimes even the next day

I’m really bad at predicting what the hardest part of my day will be, which is humbling. I’m excited to review the data in my journal after 2-3 months because I suspect it’ll reveal some blind spots I have in my life

Here’s the background on why courage matters so much to me, and why I’m so interested in trying to cultivate it in myself and the organizations I’m part of:

The first obstacle to being better at anything is laziness. If we don’t get off our behind, we can’t figure out the easy stuff. This is the case for being a better spouse, parent, citizen, athlete, accountant, corporate executive, chef, team leader, musician, change agent, or gardener.

Any domain has fundamentals that are easy to learn, but just take work. We’re lucky that in our lifetimes this is true.

Before things like youtube, google, and the internet more generally I suspect it was much harder to learn the basics of anything - whether it was baking bread, grieving the loss of a loved one, personal finance, or designing a nuclear reactor. But the obstacle of laziness remains, if we don’t get out of bed we don’t get better anything.

Eventually, however, the easy-to-learn-if-you-do-the-work fundamentals are already done, because we, correctly, tend to do those first. At that point, all that’s left is hard. So we have a choice: do the hard stuff, or stop growing.

As I’ve gotten to the age where all that’s left is hard or really hard, I’ve become more and more interested in courage. Courage, as I define it, is the ability to attempt and do the hard stuff, even though it’s hard. For this reason courage, to me, is the king of all virtues: it helps us to do everything else hard, including building our virtues and character.

This is a broadly applicable skill because there are all sorts of hard things out there: technical challenges, situations requiring patience or emotional labor, bouncing forward through adversity, product innovation, leading others through solving complex problems, being vulnerable, managing large projects, having a happy marriage, being a parent…the list goes on.

Courage matters, because it is fundamental for us to even attempt the hard stuff once the low-hanging fruit in our lives is gone. Although it is non-trivial, developing courage in ourselves and our organizations matters a lot and can make a huge difference for ourselves and those we seek to serve.

Khan Academy, but for learning leadership

We need to be developing leaders by the millions. Yet, leadership development feels like this exclusive club that you have to be anointed into.

Leadership is hard, but not complicated. Why not demystify it?

Leading teams is hard, but it’s not complicated.

Leadership has all this mystique around it, and it drives me crazy. It’s like you have to be one of the chosen ones, have some purported “natural” aptitude, or go to a fancy graduate school to be a veritable leader.

I think all these stories we tell ourselves about leadership are dogma. And hogwash.

The way I see it, leadership is a choice. If you choose to lead, take the responsibilities that come with leading, and work hard to get better at it, you’re a “leader”. Full stop.

The way I see it, the demand for people who choose to lead outstrips supply. For a peaceful, prosperous, vibrant, sustainable world we need SO many capable leaders.

We need leaders on every block in every neighborhood. We need leaders on every team in every company, large or small. We need leaders for every book club, sewing group, community service organization, and every non-profit organization. We need leaders in every family and circle of friends, probably more than one each. We need leaders in every civic group, every bible study in every church, and every youth sports team, every library, and school classroom.

I don’t have empirical data to back this up, but here are some illustrative numbers, to size up the prize here.

Let’s say…9 out of every 10 people above the age of 14 are capable enough leaders. That may be generous, but roll with me on this.

Let’s also say that after you count every neighborhood block and every church, every team and company, and every group - large or small - that needs capable leadership, the numbers say that requires 93% of people above the age of 14 to be capable enough leaders.

Let’s say that 93% figure assumes people who are capable of leading will lead in more than one area of their life.

If the demand for leaders is 93% of people over age 14 and the supply is 90% of people over age 14 - that means we’re 7.9 million leaders short. And that was (hopefully) being generous that 90% of people are capable leaders. (Here’s the link to population estimates used).

Even if those numbers are not precise, and are merely direction, the conclusion stings. Unless we’re incredibly close to the pin, we could have a leader deficit in the millions.

In my experience, being trained or designated as leader is some ridiculous, exclusive club you have to be anointed into, which is the exact opposite of what we need. We don’t need to be thinking about developing capable leaders by the dozens, thousands, or even the hundred thousands. We need to be developing leaders by the millions.

Leadership is hard, but it’s not complicated.

It can be explained. I personally feel like it’s made to feel like a secret club, because it benefits the people who are in on the joke, so to speak. If there’s a shortage in the supply of leaders, those who figured it out can raise their prices - whether that’s charged in money or status.

I’ve started an experiment to try chipping away at this problem.

Why not try to explain some of the basics of management and leadership that apply to every team in any domain, just like Khan Academdy does for so many other subjects? Why not try to make leadership simple enough for anyone who wants to learn?

You can check the first video I’ve posted on a new YouTube channel called “Leadership in 10 minutes”. It takes a simple, universal, concept of leadership and explains it in 10 minutes or less.

The first video is on “strategic planning”, which is a super complicated way of saying, “figure out what to do.”

Good, bad, or ugly, I’d love your feedback on how to make it better or your guidance to abandon the experiment if what I’ve tried to do is just not helpful at all.

The Power of Thinking in Flywheels

Feedback loops are what underpin huge changes in our world. Understanding what Jim Collins dubbed “the flywheel effect” is essential learning for anyone trying to lead or change culture.

These are learnings I’ve had trying to apply flywheel thinking in my world, over the past 2-3 years. Flywheels have helped me to understand everything from business strategy, to management, to gun violence prevention, and even my own marriage.

There are two types of growth, generally speaking - linear growth and exponential growth. And I’m not just talking about for a corporation, but for teams, culture, families, and ourselves as individuals.

The problem with linear growth is diminishing marginal returns - once your market is saturated you have to spend more and more to get less and less. The problem with exponential growth is that it’s hard and also doesn’t last indefinitely. (Sustaining exponential growth is a topic for a different day.)

Jim Collins developed an interesting concept to make exponential growth less hard, which I find brilliant - the flywheel effect. Flywheels are basically a way of thinking about a feedback loop, deliberately. He explains it well in this podcast interview with Shane Parrish on the Knowledge Project. Some of the key takeaways for me were:

The goal of a leader is to remove friction from the flywheel, because once you get it turning, it builds momentum and starts moving faster and faster.

Each step of the flywheel has to be inevitable outcome of the previous step. Think: “If Step 1 happens, then Step 2 will naturally occur”

The key to harnessing flywheels aren’t a silver bullet or Big Bang initiative, it’s a deliberate process of understanding what creates value and building momentum - slowly at first, but then accelerating. To the outside it’s an overnight breakthrough, but to the inside it was a disciplined, iterative process to understand the flywheel, and reducing friction to get it cranking

I was introduced to this concept when I read Good to Great years ago, and was reintroduced to it before the Covid pandemic. Only recently has it started to click.

I’ve found flywheels to be a transformative way of thinking, both at work and in my real life. Here are a few examples of flywheels I’ve experienced and experimented with.

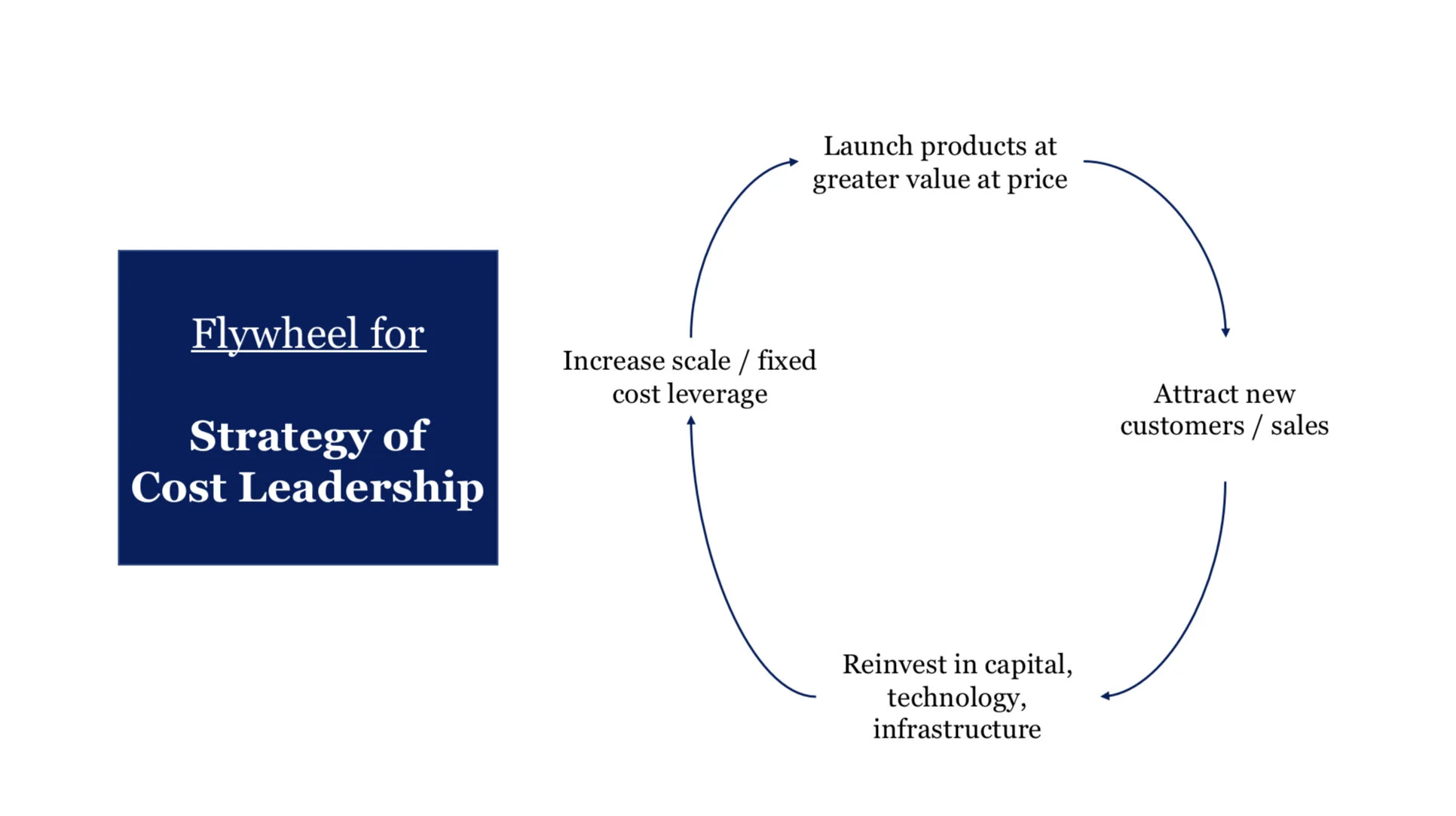

Most business types will be familiar with strategies of differentiation or cost leadership. Both are powerful, value-creating flywheels:

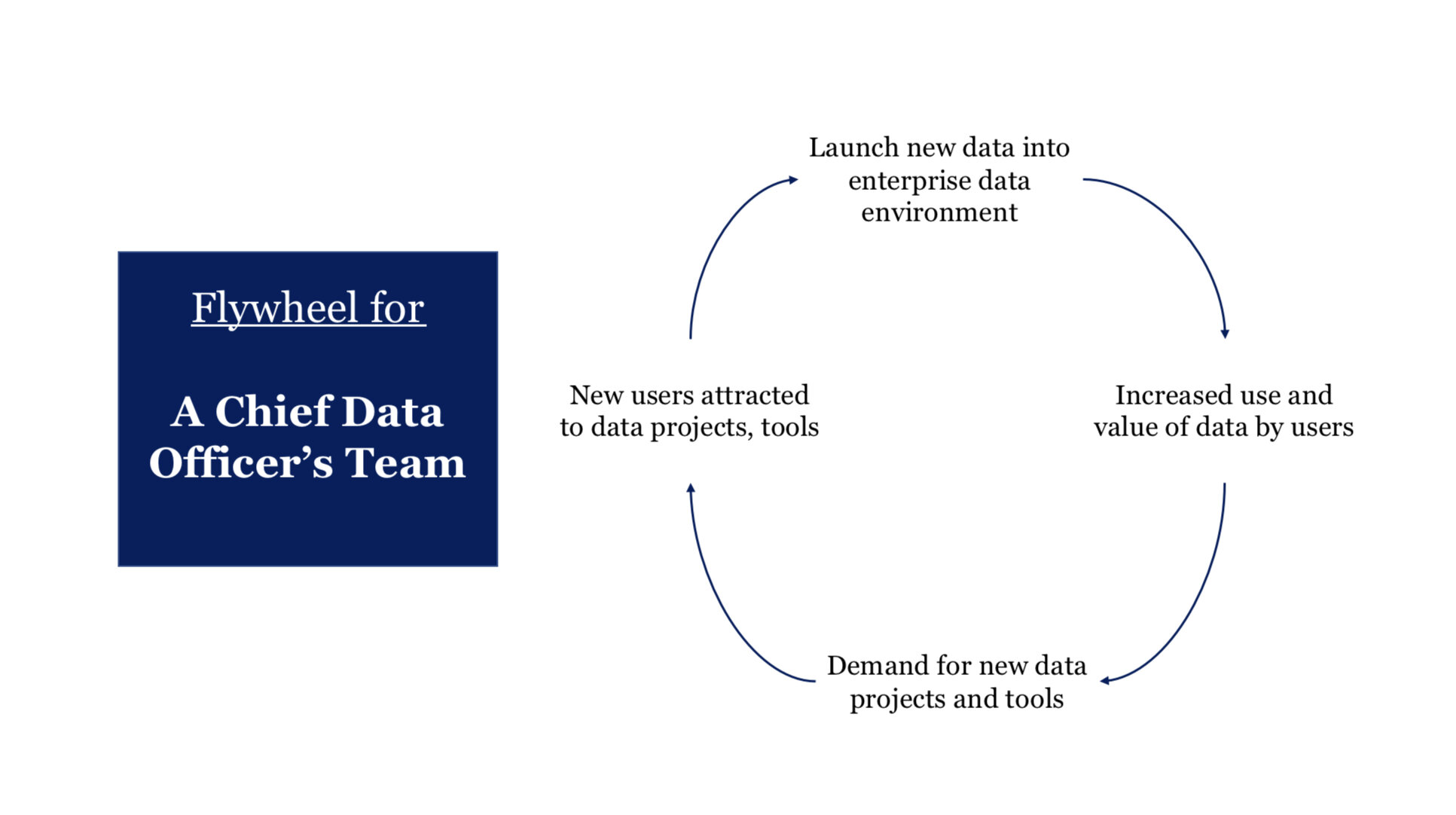

Flywheels are even helpful at the business-unit level. This is an example of how a Chief Data Officer might think about how to create a data-centric culture within their organization.

When experimenting with flywheel thinking, it turns out Robyn and I have been operating a flywheel of sorts within our marriage, and temperature check has been a big part of that.

This is also a good example of how flywheels need to be specific to the stakeholders involved in them. This flywheel doesn’t work for every marriage. Among just our friends, I’ve seen flywheels that are organized around faith or civic engagement.

Gun violence is an interesting example of flywheel thinking because it helps illustrate how particularly complex domains can have multiple flywheels intertwined within them. These are just two dynamics I observed when working on violence prevention initiatives.

Each flywheel has different stakeholders and explain different categories of violence: at the left it’s more about influencing perpetrators making a “business decision” to shoot, at right it’s more about influencing members of trauma-afflicted communities that tend to have simple arguments end with gunfire, usually unintentionally and without pretense.

How we manage and coach is also a classic example of a feedback loop that operates like a flywheel. It’s simplicity doesn’t make it any less powerful, or easy to do in practice.

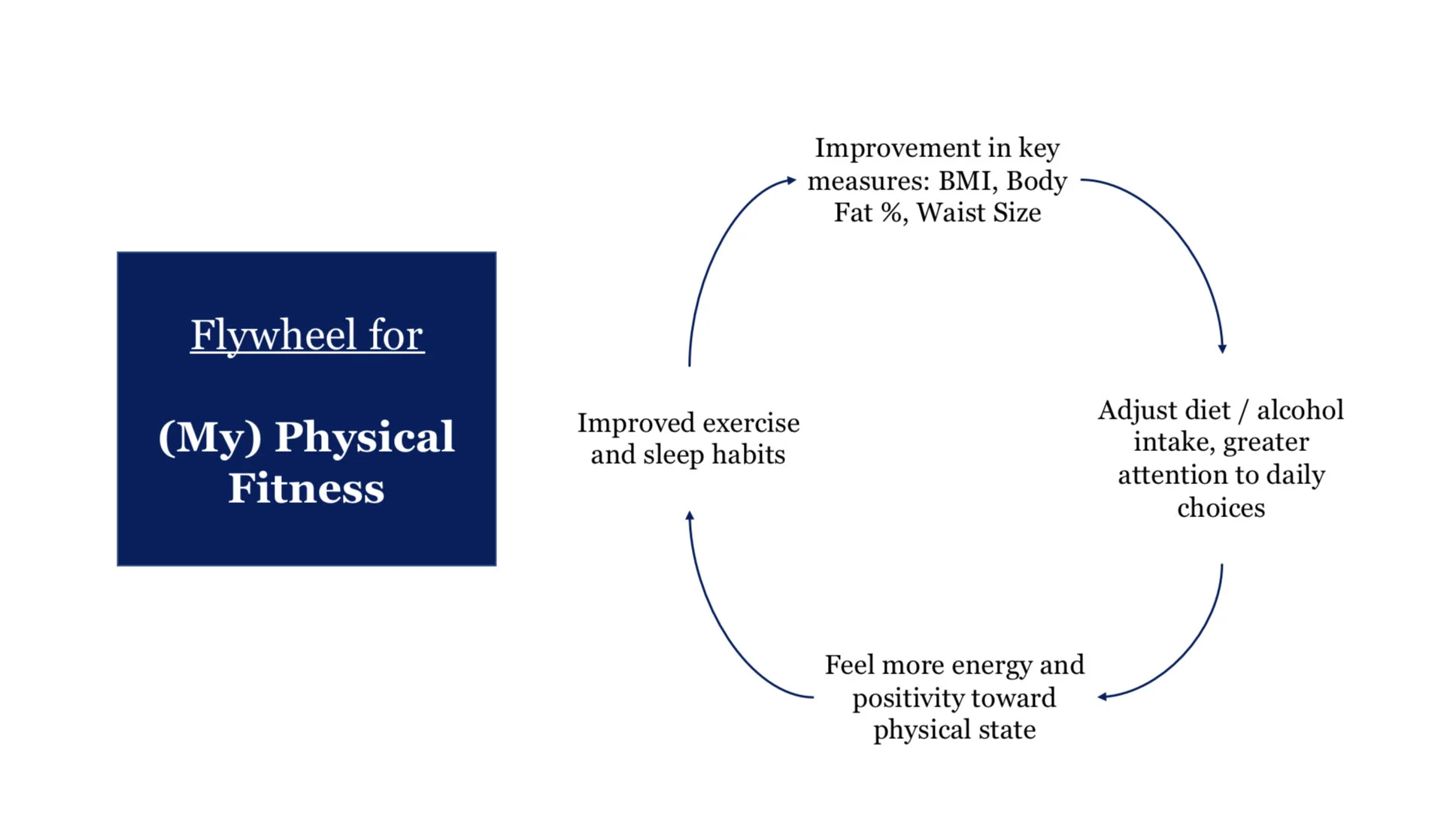

We also have flywheels that explain our behavior as individuals. For me, this is how I specifically respond well to improve my physical fitness.

My flywheel really took off when I understood and started measuring my BMI, Body Fat%, Sleep, Blood Pressure etc. I happen to love the products from Withings because they made the flywheel much more transparent to me as it was occurring, which led to rapid and permanent changes in my behavior.

Social movements utilizing nonviolence techniques (i.e., think US Civil Rights Movement, India Independence) also seem to fit the concept, showing the breadth of flywheel thinking’s explanatory power.

Going through this exercise of identifying flywheels in a number of domains I’m familiar with, I’d offer this practical advice for articulating flywheels in your world:

Think about what is valuable to each involved party. At its core, flywheel thinking is rooted in an understanding of what drives value for everyone. What are the things that if increased or decreased would create win-wins for everyone involved? If the flywheel doesn’t encompass value creation for everyone involved, it’s probably not quite right. Zero-sum flywheels, which create winners and losers between the flywheel’s stakeholders aren’t sustainable because someone will end up trying to sabotage it.

Mind magical thinking. The beauty of the flywheel is that each step in the process is a naturally occurring inevitability of the previous step. Which means as a flywheel detectives we have to be honest about how the world really works; the flywheel has to reflect what the parties involved will actually do in real life and what they’re actually motivated by.

Identify agglomeration. In every flywheel there’s a step where some sort of resource accumulates, and that resource is one where it’s value and impact increases exponentially the more you have of it. That resource could even be things that aren’t technologies or infrastructure (cost leadership example), like data (chief data officer example), knowledge (managing / coaching example), or moral standing (social movement example).

I didn’t use an example with a network effect, but the same idea applies. These agglomerations are all critical resources to the exponential growth unlocked by the flywheel, so if you’re not seeing evidence of that sort of resource agglomeration, the flywheel is probably not quite right.

Identify interactive feedback points. Additionally, there seems to be a step in each flywheel where there is feedback or a learning interaction between the stakeholders participating in the flywheel. Maybe it’s learning about the customer (differentiation strategy example), or maybe it’s response to a measurement (physical fitness example). If there’s not interactive feedback happening, the flywheel is probably not quite right.

I wanted to share this post because applying flywheel thinking is a huge unlock for value creation. It helps, me at least, to get beyond linear thinking and operate at a higher level of effectiveness and purpose.

I get especially excited by how this thinking can apply across disciplines. Jim Collins, who pioneered the concept, is a business guru. But the concept applies broadly, and far beyond what I even suggested - I can imagine it being used to inform feedback loops influencing decarbonization, community development, or regional talent clustering and entrepreneurship.

But flywheel thinking can also be used for nefarious purposes. Rent-seeking and political corruption feedback loops are good examples of this. Specifically, a flywheel like this quickly comes to mind:

My bet is that the sort of people who know me and read my writing are disproportionally good people. By sharing this learning I’ve had, I suppose it’s me trying to do my part create a feedback loop for a community of practice that uses flywheel thinking to make the world a better place.

Diversity: An Innovation and Leadership Imperative

I was listening to a terrific podcast where Ezra Klein interviewed Tyler Cowen. And Tyler alluded to how weird ideas float around more freely these days - presumably because of diversity, the internet, social media, etc.

I think there’s a lot of implication for people who choose to lead teams and enterprises. How they manage and navigate teams with radically more diversity seems to be a central question of leadership today.

If you have any insights on how to operate in radically diverse environments, I’m all ears. Truly.

The US workforce is more diverse and educated than previous decades. And it’s getting more diverse and educated. This is a fact.

This transformation toward diversity is a big challenge. Because as any parent knows, a diversity of opinions leads to deliberation and friction. Managing diverse organizations is really, really hard - whether it’s a family, a volunteer organization, or a team within a large enterprise.

I’ve seen leaders respond to diversity in one of four ways:

Tyranny is fairly common. If you don’t want to deal with diversity, a leader can just suppress it - either by making their teams more homogenous or shutting down divergent ideas. The problem here is that coercive teams can rarely sustain high performance for extended periods of time, especially when the operating environment changes. Tyrannical leaders exterminate novel ideas, so when creative ideas are needed to solve a previously unseen problem, they struggle. Tyranny is also terrible.

Conflict avoidance is also fairly common. These are the teams that have diversity but don’t utilize it. On these sorts of teams, nobody communicates with candor and so diverse perspectives are never shared and mediated - they’re ignored. As a result, decisions are made slowly or never at all because real issues are never discussed. By avoiding the friction that comes with diverse perspectives, gridlock occurs.

Another response is polarization. Environments of polarization are unmediated, just like instances of conflict avoidance. But instead of being passive situations, they are street fights. In polarized environments, everyone is a ideologue fighting for the supremacy of their perspective, and nobody is there to meditate the friction and make it productive. Similar to conflict avoidance, polarization also leads to gridlock. I don’t often see this response to diversity in companies. But it seems a common phenomenon, at present, in America’s political institutions.

What I wish was more common was productive mediation of diversity. Something magical happens when a diverse-thinking group of people gets together, focuses on a novel problem, candidly shares their perspectives, and then tries to solve it. Novel insights emerge. Divergent ideas are born. New problems are solved. A more common word for this phenomenon is “innovation”.

It seems to me a central question in leadership of organizations today, maybe THE central question of leadership today is “how to do you respond to diversity?” Because, as I mentioned and linked to above - the workforce has become more diverse and more educated. Which means the pump is primed for lots of new, weird ideas and lots of conflict within enterprises.

Leaders have to respond to this newfound diversity. And whether they respond with tyranny, conflict avoidance, polarization, or productive mediation matters a great deal.

I wanted to share this thought because I think this link is often missed. Leadership is rarely cast as a diversity and innovation-management challenge, and diversity is usually cast as an inclusion and equity issue rather than as an innovation and leadership imperative.

The types of questions asked an interviews are a good bellwether for whether enterprises have understood the nuance here:

A traditional way to assess leadership: “Tell me about a time you set a goal and led a team to accomplish it.”

A diversity and innovation-focused way to assess leadership: “Tell me about a time you brought a team with diverse perspectives together and attempted to achieve a breakthrough result.”

The person who has a good answer to question one is not necessarily someone who has a good answer to question two, or vice versa. The difference matters.

Reactions Make Culture

I agree with statements like, “culture matters” or “leaders set the tone”, but they’re not helpful. Everyone knows that, and yet cultures don’t change easily.

It seems to me that one specific vector to change culture is to focus on reactions. I’ve reflected on some work-related examples in the post below. But the idea crosses domains, in my experience at least.

Are there are places where you’ve seen reactions have a big impact on organizational culture?

Typically, at work…

When a project goes “red” the team is usually made to feel embarrassed. What if the executive sponsor thanked them for raising the problem quickly instead?

When someone is promoted there’s often a department wide email talking about their accomplishments and new role. What if we celebrated their mentors just as vigorously?

When someone goes out on vacation they usually leave an out of office message. What if the email administrator turned off their email access while they were away as a matter of protocol, too?

Email signatures usually include a job title. What if that line was instead used a sentence about the team’s purpose or why the sender is personally invested in the organization’s mission?

Project meetings often start with some version of a status update. What if they started with, “what’s something important we learned this week” instead?

Maybe it’s not always clear whether it’s better to light a candle or curse the darkness. But the lesson remains: how we react shapes, defines, and amplifies the culture.

And not just at work, but in families, churches, book clubs, soccer leagues, marriages, and political discourse too.

Rotation of Powers

Separation of Powers is a brilliant way of preventing concentration of power (and eventually tyranny). Rotation of Powers is an alternative approach.

Separation of powers is a brilliant idea.

Managing power in organizations and institutions is a huge problem. Because when power is concentrated and left unchecked, tyranny happens. Separation of powers (and checks and balances) solves this problem brilliantly in the US constitution. By turning power against itself, it keeps any one part of government from dominating the others. The US Constitution is a gold standard case study in the management of power to prevent tyranny.

To me, preventing tyranny is among the most important organizational problems there are. Because under tyranny, people waste their talents and do not flourish. Because under tyranny, people suffer and have their basic human rights violated. Because under tyranny, culture decays rather than grows. Preventing tyranny is a huge deal.

In this essay, I offer Rotation of Powers - an alternative approach to managing power in organizations. I offer this idea in addition to separation of powers, not as a replacement to it, for two reasons. One, the challenge of preventing tyranny is so important we ought to be working on many solutions to this difficult problem - diversity and redundancy create long-term resilience. Two, because of information technology and advances in our understanding of management, the alternative of rotation of powers is possible in ways that were not even conceivable 10-15 years ago.

What is Rotation of Powers?

In hierarchical organizations, leadership and power is role-based. Power lies in the principal and senior executives of an organization. The idea of rotation of powers is that the people in power go into their reign expecting that they will rotate in and out of their role as “leader”. I take a turn, then you take a turn, then our colleague takes a turn being the “boss”. And then eventually, I know I’ll have to take a turn again. And we rotate, on and on, and let others join and leave the rotation as we go.

So unlike separation of powers, where the idea is to split up the power into different branches that can check each other, the idea of rotation of powers is to not let anyone stay in power long enough to become entrenched, and, to make them them feel the externalities of their decisions - both because they’ll be under the power of someone else soon, and, if they leave someone else a mess it’ll come back around. Instead of checks and balances, the operating principle of Rotation of Powers is “incentivize positive reciprocity”.

Here’s an example of how this might actually work.

I’m on team at work. Let’s call them the Knights. And without going to to too many details, the Knights try to improve our processes so that our customers are happier. It’s a team that formed from the “bottom-up”, so to speak, and operate using the principles of agile software development, more or less.

At the beginning, there were about 3 people who operated as Scrum-Masters for the team, which we call “Lance-a-lots”. The role of the Lance-a-lot is to facilitate our sprint planning sessions, and elicit input from the Knights to determine which projects folks think are important. Knights then self-select onto project teams for the 6-week sprint and the Lance-a-lot leading that particular rotation checks-in on teams to make sure progress is happening.

The group of Lance-a-lots meets weekly and consults with each other on how things are going, and how to manage the team more effectively. Anyone who wants to be a Lance-a-lot is free to join the rotation, and the Lance-a-lot group has grown from 3 to 5 in the 6 months this team has been around.

Right from the beginning, we rotated the role of the person serving as Lance-a-lot. Which means, in practice, that the person running the meeting and responsible for ensuring forward motion changed every 6 weeks.

The success of the Knights remains to be seen. It’s a nascent team, and kind of like a startup we’re trying to lock-in to a value proposition that works. But that said, it’s an incredibly uncommon organizational form and the culture of the team feels different than the traditional, corporate, hum-drum, hierarchical working group. It feels less top-down and tyrannical, more equal and democratic. Relatively speaking, at least.

Why might Rotation of Powers work?

What you’ll notice about the Knights example I gave above, is that rotation happens in two ways. One, the “Lance-a-lot” rotates every 6 weeks. Second, people move in and out of being part of the Lance-a-lot rotation. That creates an interesting dynamic that prevents power concentration.

First, no one person has the title of “leader” of the team. Nobody can lay claim to it. Nobody is burdened with an ongoing responsibility or could even lay claim to holding power if they tried. And, the role of Lance-a-lot is wide open because anyone who wants to can opt-in to the rotation. So, in practice, it feels like an organization that has leadership, but doesn’t have an absolute leader. And a sort of selection effect occurs as a result of this, anyone who is driven by the prestige of being an exclusive, role-based leader and having power wouldn’t want to opt into the rotation, because they’d never be the absolute leader of the team.

Second, at meetings of Lance-a-lots you really have a positive pressure to make good, collaborative decisions. Because Lance-a-lots have opted-in, their reputations amongst the team are especially on the line for doing a good job. And, because you know you’ll be the Lance-a-lot in a few rotations it pushes you to make a contribution and get your ideas out now - you don’t ever want the team to be in bad shape, so when it’s your turn you can make progress.

The dynamic of Rotation of Powers makes two things very clear: one, that power will, by definition, take turns so there’s no reason to be an ego-maniacal jerk about it. And two, that if you do right by the team and others you’re going to reap the benefits, and that if you leave a mess you’re shitting where you eat, so to speak.

What are the operational implications of Rotation of Powers?

Of course, this approach has trade-offs and operational challenges. Here are a few “must-haves” that I would assume have to be in place for a scheme of Rotation of Powers to work.

A compelling, clear mission - Rotation of Powers doesn’t have the benefit of glory and spotlight. So for anyone to opt-in to the leadership rotation, they have to really care about the mission. Defining a clear and compelling mission is not easy, and would have to explicit and well understood, I think, for Rotation of Powers to work. Otherwise, nobody would opt-in to the rotation.

Knowledge Management - For Rotation of Powers to work, the rotation has to happen quickly enough so that any one person cannot entrench themselves in power and seek rents. Transition is not easy. And in a scheme of Rotation of Powers, there would have to be good systems of knowledge and decision management to ensure transitions happened smoothly. If not, the organization would always be in a cycle of onboarding, and never have forward momentum.

Trust and Collaboration - Similarly, if rotation is happening there has to be strong trust and collaboration among the rotating leadership team so that the direction of the team is one that has enrollment. A team would fail if with each rotation the particular leader during that rotation took the team in a whole new direction. The people in the rotation have to be on the same page for Rotation of Powers to work.

Transparency and openness - A big challenge would preventing the people in the rotation from becoming insular and eventually self-aggrandizing. So, the leadership rotation would have to have transparency and openness to ensure what they were doing was appropriate. And, the people in the rotation would have to change over time so that the same old people don’t end up losing touch with what’s happening on the front line.

And so this approach maybe doesn’t work well in all contexts. Maybe it’s especially suited for mission-driven organizations (I happen to believe that all organizations should be mission-driven, but that’s a different blog post). And maybe it doesn’t work well in an environment where there’s a lot of specialized knowledge that’s accumulated over time, or ones where compliance to rules and protocol is really important.

But I could see something like this working for cooperatives, B-Corps, and maybe even larger public or social sector organizations. Additionally, it’s an approach that could be used within large corporations, in functions where innovation and dynamism is needed and more democratic styles of management which allow for experimentation are a strategic advantage.

Why now?

Like I said before, having more tools in our toolbox for managing power to prevent tyranny seems like a good idea because the stakes are so high. But this idea of Rotation of Power seems much more feasible than it did even 10 years ago. 50 years ago, this approach to organization design probably wasn’t even possible. Here are a few reasons why:

Information Technology - the sort of transparency and knowledge management needed for Rotation of Powers simply was not possible before advances in information technology. Doing things like recording decisions, meetings, and real-time, cross-location, communication simply wasn’t possible because it would be administratively overwhelming. Now we have all these tools to collaborate and manage knowledge decisions, and expertise, which mitigates one of the most difficult operational implications I listed above.

Understanding of Bureaucracy - The bureaucratic form of organization and management of large enterprises is a relatively discipline. We now know much more about how to manage organizations and establish missions and purpose, it’s actually something we can start to teach. So, now we actually know better how to create purpose-driven organizations, which again, mitigates a key operational challenge I mentioned earlier.

Upskilling of Talent - Lots more people have higher levels of education and leadership experience. And if you have to rotate, the talent level of the team has to be sufficiently high and skills need to be sufficiently developed. A lot more people probably have those skills than they did 50 years ago. And honestly, rotating power probably accelerates that upskilling because more people get more reps leading teams.

Emerging Technology - I’m intrigued by the use of blockchain technology and Decentralized Autonomous Organizations (DAOs). Using software-based rules could automate some of the management of new forms of organizations (including Rotations of Power) that reduce administrative burden, and ensure that rotations are fair and that the tracking and tracing of decision rights can be effectively managed. I’m not a blockchain expert, but these sorts of ideas make the idea of experimenting with Rotations of Power seem more realistic.

Conclusions

Overall, I acknowledge that this is really a thought experiment. But I think it’s an interesting one that’s worth doing - as the world changes we need more ways to manage power and prevent tyranny, because separation of powers might not work forever. Our freedom and welfare is too important to depend on what will eventually become an old idea.

And, yes, the criticism of “that’s a cool idea, but it would never work in real life” is a valid criticism because I don’t know that it would work, especially at scale. But I would argue that we probably didn’t realize if separation of powers would work at the beginning, and we evolved it as we went. The same has been and would be true of any organizational form.

At a minimum, I hope this thought experiment validated that there are alternatives to separation of powers, to solve the problem of unchecked power and tyranny. It’s a big problem that’s worth thinking about and experimenting with.

Who is low-potential, exactly?

We have exclusive programs for people with “high-potential”. If we do that, then who exactly is “low-potential”?

There are lots of organizations that have programs for “high-potentials”, cohorts of “emerging leaders”, or who’s who lists for “rising stars”.

But lately, I’ve wondered: if we have programs for “high-potential” talent, who is “low-potential”, exactly? It’s audacious to me that we consider anyone low-potential.

With the right role, coach, opportunities, and expectations, my experience suggests that just about anyone can grow and thrive and make a tremendous contribution to whatever organization they are part of. Moreover, in my experience the most important ingredient needed for someone to be “high-potential” is that they want and are motivated to grow and be better.

It seems to me that a better approach than creating high-potential programs or leadership development cohorts that are exclusive is to design them in such a way that anyone who wants to opt-in and put in the work can participate.

And wouldn’t that be better anyway? Aren’t our customers, colleagues, shareholders, and culture all better off if everyone who wanted to had a structure where they could grow to their fullest potential? Even if not everyone ends up being a positional leader, don’t we want every single person in our companies to be better at the behavior of leading?

I don’t buy the excuse that it would take too many resources to design structures for developing potential that’s inclusive rather than exclusive. Software makes interaction much cheaper and scalable. People are really good at developing themselves and learning from their peers, given the right environment. And, in my experience most people are willing to coach and mentor someone coming up if that person is eager to learn and grow.

I definitely would want to be persuaded in a different direction,.however. Because to me, employing the best ways to prevent human talent from being wasted is worth doing, even if it’s not my idea that wins.

But again, if someone is truly motivated to grow and make a greater contribution, who of those folks are low-potential, exactly?

Status fights and wasted talent

What to do if your company feels like a high-school cafeteria.

Companies, and really any organization, can function like a fight for status. This “fight” plays out in organizations the same way whether it’s a corporation, a community group, or a typical school cafeteria.

There’s a limited number of spots at the top of the pecking order, and the people up there are trying to stay there, and those that aren’t are either trying to claw to the top or survive by disengaging and staying out of the fray.

If you’re engaged in a fight for status there are two ways to win, as far as I can tell: knocking other people down or promoting yourself up.

Knocking other people down is what bullies do. They call you names in public, they flex their strength, they form cartels for protection, and they basically do anything to show their dominance. They become stronger when they make others weaker.

This is, of course, easy to relate to if you’ve ever been to middle school or have seen movies like Mean Girls or The Breakfast Club. However, the same sort of dominating behavior that lowers others’ status occurs in work environments.

“Bullies” in the work environment do things like interrupt you in a meeting, talk louder or longer than you, take credit for your work, exclude you from impactful projects, tell stories about your work (inaccurately) when you’re not there, pump up the reputation of people in their clique, or impose low-status “grunt work” on others. All these things are behaviors which lower the status of others. In the work environment, bullies get stronger by making others weaker.

The other way to win a status fight is to promote yourself up and manage your perception in the organization. In the work environment, tactics to promote yourself up include things like: advertising your professional or educational credentials, talking about your accomplishments (over and over), flashing your title, hopping around to seek promotions and avoid messy projects, or name dropping to affiliate yourself with someone who has high status.

Let’s put aside the fact that status fights are crummy to engage in, cause harm, and probably encourage ethically questionable behavior. What really offends me about organizations that function as a status fight is that they waste talent.

In a status-fight organizations people with lower status are treated poorly. And when that happens they don’t contribute their best work - either because they disengage to avoid conflict or because their efforts are actively discouraged or blocked.

Think of any organization you’ve ever been part of that functions like a status fight. Imagine if everyone in that organization of “lower status” was able to contribute 5% or 10% more to the customer, the community, or the broader culture. That 5 to 10% bump is not unreasonable, I think - it’s easy to contribute more when you’re not suffocating. What a waste, right?

Of course, not all organizations function like a status fight and I’ve been lucky to have been part of a few in my lifetime. I think of those organizations as participating in a “status quest” rather than a “status fight”. In a status-questing organization, status actually creates a virtuous cycle rather than a pernicious one.

A status quest, in the way that I mean it, is an organization that’s in pursuit of a difficult, important, noble purpose. Something that’s aspirational and generous, but also exceptionally difficult.

In these status-questing organizations the standard for performance (what you accomplish) and conduct (how you act) is set extremely high, because everyone knows it’s impossible to accomplish the important, noble, quest unless everyone is bringing their best work everyday and doing it virtuously.

And when the bar is set that high, everyone feels the tension of needing to hit the standard, because it’s hard. Whether it’s to achieve the quest or be seen by their peers as making a generous contribution to the organization’s efforts, everyone wants to do their part and needs the help of others.

And as a result, the opposite dynamic of a status fight occurs. Instead of knocking other people down, people in a status-questing organization have no choice but to coach others up, which ultimately raises everyone’s status.

If you’re on a noble quest, there’s plenty of “status” to go around and the organization can’t afford to waste the contribution of anybody in the building - whether it’s the person answering the phone or a senior executive. In a status-questing organization, the rational decision is to raise the bar and coach instead of throw other people under the bus.

And what’s nice, is that in an organization with that raise-the-bar-and-coach-others-up dynamic is that the bullies don’t succeed, because their inability to raise and coach is made visible. And then they leave. And so the virtuous cycle intensifies.

So if you’re in an organization that feels more like a high-school cafeteria than an expeditionary force of a noble, virtuous quest, my advice to you is this: raise the bar of performance and conduct for the part of the organization you’re responsible for - even if it’s just yourself. And once you raise the bar, coach yourself and others up to it.

And when you do that, you’ll start to notice (and attract) the other people in the organization who are also interested in being on a noble quest, rather than a status fight. Find ways to team up with those people, and then keep raising the bar and coaching up to it. Raise and coach, raise and coach, over and over until the entire organization is on a status quest and any “bullies” that remain choose to leave.

Of course, this is one person’s advice. Looking back on it, it’s how I’ve operated (but I honestly didn’t realize this is how I rolled until writing this piece) and it’s served me well. Sure, I haven’t had a fast-track career with a string of promotions every two years or anything, but I have done work that I’m proud of, I’ve conducted myself in a way that I’m proud of, and I have a clear conscience, which has been a worthwhile trade-off for me.

—

Note: this perspective on equality / the immorality of wasted talent is well-trodden ground, philosophically speaking. John Stuart Mill (and presumably his contemporaries) wrote about it. Here’s an explainer on Mill’s The Subjection of Women from Farnam Street that I just saw today. It’s a nice foray into Mill’s work on this topic.

Damn it, let's give our kids a shot at choosing exploration

I dreamed of exploring space, but the problems of earth got in the way of that. I hope our kids can truly choose between exploration and institutional reform.

In retrospect, this isn’t the vocation I was supposed to have. It was put on me, or at least started, by an act of God. But my path within the universe of organizations - a mix of strategy, management, public service, and innovation - was never supposed to happen.

I had always, in my heart of hearts, set my mind on space. I knew I would probably never be an astronaut. For a multitude of reasons I would’ve never had a path to the launchpad - being an Air Force pilot or bench scientist wasn’t me. I won a scholarship to Space Camp when I was in 4th grade and I got to be the Flight Director for one of our missions. And from then on, I dreamed of being on a team that reached outward and put a fingerprint on the heavens.

Five years later, a mosquito was never supposed to bite my brother Nakul -when I was 13 - thousands of miles away in India. That mosquito was never supposed to give him Dengue Fever. He was never supposed to be patient zero of the local outbreak and die from it. None of that was ever supposed to happen, but it did.

And, when he died, I got hung up on something. I didn’t get caught up on curing the illness itself. I didn’t feel called to become a biologist, epidemiologist, or a physician. What I couldn’t for the life of me understand is how in the 20th century, with all its wealth and medical progress, could Nakul not receive the treatment - which humankind had the capability to administer, by the way - he needed to survive Dengue Fever? How was Dengue Fever still a thing, in the first place? How could governments and health care systems not have figured this shit out already?

The problem, as I saw it then, was institutions. His death, and millions of others across the world, could be prevented with institutions that worked better. And the vocation that called out to me shifted, and here I am.

—

Watching kids watch Christmas movies is interesting. You can see their body language, facial expressions and language react to the imagination and wonder they’re observing. Their bodies seem like they’re preparing to explore, just like their minds are. They light up, appropriately enough, like Christmas lights. It’s really something to see a child imagining.

For our boys, right now, anything in the world is possible. Any vocation is on the table for them. They can dream of exploring. They can dream of applied imagination. They can dream of storytelling and art. They can dream of so much. At this age, I think they’re supposed to.

What occurred to me, while watching them watch Christmas movies, is that I don’t want them to be drawn into the muck like I was.

I was supposed to be exploring space, but plans changed and now I’m firmly planted on earth, in the universe of human organizations. I am definitely not charting new territory, rather, I’m fixing organizations that should never have been broken in the first place. I am not an explorer, I am a reformer. There was no choice for me, the need for reform here on earth was too compelling for me to contemplate anything else.

But for our children, mine and yours too, let’s give them a choice. Let’s figure out why our institutions seem to be broken and do something different. Let’s figure out why our social systems seem to be broken and do something different. Let’s not let institutions be a compelling problem anymore. Let’s take that problem off the table for them. Let’s complete this job of reform - both of our organizations and our individual character - so they don’t have to.

Maybe some of our children will want to follow in our footsteps and be reformers, but damn it, let’s give them a chance at choosing exploration instead.

Preventing violence and madness, through abundance, strong institutions, and goodness

A theory on how to create a community that resolves conflict without violence and madness. It takes three supra-public goods: abundance, strong institutions, and goodness.

If we live in a community, rather than isolated in the woods fending for ourselves, conflict is inevitable. We are all imperfect humans, after all.

And in my mind that leads me to suggest one, bedrock aspiration that we all must have to live in a community: the conflicts we can’t avoid are settled without violence and a dissolution into madness.

But how?

To do that, I think we must create three supra-public goods: abundance, strong institutions, and goodness.

Abundance is important because it creates surplus. Surplus is important because it prevents us from squabbling over the fundamental resources we need to survive and have a life beyond mere subsistence. It also creates the space for generosity, culture, scholarship, art, and human flourishing.

Strong institutions are important because they create norms. Norms are important because they provide guardrails to ensure nobody behaves so peculiarly that they cause widespread and unbridled harm. Norms are also important because they provide accepted processes for mediating conflict when it inevitably happens.

Goodness is important because it creates trust. Trust is important because it prevents conflict in the first place. When people are good to each other, they give each other the benefit of the doubt and are more likely to let things slide or work out an issue, rather than skipping straight to punching their lights out. Trust is also nice because it reduces the need for concentrated bodies of power to enforce the norms laid out by institutions.

The big eureka moment for me is that we really need to grow in all three areas simultaneously. One or even two of this three-legged stool is enough.

A society without abundance is starving and fragile. A society without strong institutions can’t ever grow in size or manage the challenges of diversity. A society without goodness is lonely and without meaning.

To live in a society that resolves conflict without violence or dissolving into madness, these are the three things we - whether that “we” is us individually, our friends and families, or the formal organization we are part of - must all be trying to bring into the world: abundance, strong institutions, and goodness.

And again, we need all three. Not even two are enough to create a world where our children’s dreams are borne from joy and the convictions of their own souls, rather than from pain and our lesser-than-honorable impulses.

High-performing Government

High-performing Government is a conversation worth having.

As a father, I’ve relearned how incredibly gifted, skilled, and virtuous human beings can be. There are so many good things that our older son does that we haven’t taught him explicitly. He makes jokes, he voluntarily shares dessert, he hugs his brother and watches over him. He figures out problems and makes inferences. He helps to wash dishes and tells the truth (most of the time).

It’s really quite amazing. And a big turning point for me was a realization that yes, I can expect a lot from him. So I do, even though he’s only two.

He is smart, capable, and motivated. There's a lot that he’ll figure out, I’ve come to realize, if I set high expectations for him and am willing to coach him up.

The interesting thing about high expectations for little kids is that they meet them, much more than we think is possible. They are growth and learning machines. My son regresses a lot when I don’t set high expectations for him.

It’s so easy in our lives to have low expectations. And then what results is thoroughly disappointing.

I feel this way so often about government.

It bothers me so deeply - it offends me down to my core - that we have such low expectations of government. Any of these sound familiar?:

“It’s so inefficient”

“They’re incompetent”

“Every bureaucrat is lazy and dumb”

“Government never accomplishes anything”

“Every politician is corrupt”

“Government is too slow to make this happen”

“We should cut their budgets, they won’t use it well anyway”

And it goes on and on

I think we’re getting the government we deserve. If we’re not willing to have high expectations, if we’re not willing to invest, if we’re not willing to make government reform a priority - the government we have is exactly the one we should expect.

And that’s partly - maybe even mostly - on us.

If we had higher expectations, and actually backed those expectations up with actions, we’d probably have a higher-performing Government.

What if what we expected was more like this:

Our government (state / local / federal) will have a 10-year strategic plan that actually makes sense

Our government will be filled with talented, competent people - truly the best and brightest

Our government will administer services more efficiently than the private sector; because it is more important, it should

Our government will truly represents the population it serves

Our government will be honest, caring, fast-moving

Our government will have effective leaders and managers

Our government will be incredibly good at listening to the voice of the constituent

Our government will set concrete goals and measure results

When I served in the Detroit City Government, I had the highest expectations I’ve ever been asked to deliver upon. This was because my chain of command (Residents, Mayor, Chief of Police, Assistant Chief, Director, me) had high expectations. And damn it, most of the time we hit them even though it seemed impossible to even try.

We met those expectations, more than we thought was possible.

As a citizen, I see how important those high expectations are. In Detroit we didn’t even have the basics 10-15 years ago. Streetlights, trash pickup with curbside recycling, timely 911 response. And even though Detroit has a long way to go to be considered high-performing Government, the difference the last few years has made is jaw dropping. In my opinion, it’s on a solid trajectory toward high performance.

We’re going to keep getting the government we deserve one way or the other. Let’s deserve a high-performing Government.

Management is moral

Management is so much more than getting people to do what we want.

These are the three questions I think about a lot, with regard to my professional role as a people manager:

Am I here to enrich the lives of others (customers, colleagues, owners) or my own?

Are my expectations for my team (starting with myself) going to be high or low?

When my team doesn’t meet my expectations (which is bound to happen sometime) am I committed to coaching them, or merely shaming them into compliance with my wishes?

Don’t be fooled, these decisions are all moral in nature. Being a manager is not merely transactional, tactical, or even just strategic. Management is moral. Or I should say, depending on how one answers these questions, management might be moral. In my view, it ought to be.

As managers we are the stewards of whether the talent of the people we manage is wasted or not. And we steward tens of thousands of dollars worth of people’s time, if not more. For that reason, I think management ought to be a moral endeavor where we consider its moral implications.

And it starts with the expectations we set for ourselves and, in turn, others.

I persist, management is moral. We should take it that seriously.

A high five and bat signal to my working dad brethren

Working moms have been pushing for better practices for some time, and I think it’s time for us join them in a big way.

I was furloughed from my job on Monday, March 30.

As a result my wife upped her hours and I luckily fell into some part-time contract work. In normal circumstances this would be a monumental life change. But alas, in these times it’s only a contextual footnote.

We hit day 100 of staying at home with the kids, all day, this past Tuesday. It has been an awakening, particularly in how I think about being a father. The highlights of this awakening are probably not terribly different for you, if you’re also a young father.

First and foremost, it’s really damn hard to be lead parent, especially because we’re both working. I realized during this quarantine exactly how my wife puts our family on her back and carries us, day after day. It’s nothing short of astounding, and that’s not even emphasizing the economic value of that unpaid care-giving work.

But every day, I find myself thinking of this bizarre situation as a blessing. I get to be a stay-at-home dad. This was the paternity leave I never had the chance to have.

Being a working dad is frustratingly hard, and most days someone in our house has a meltdown, despite my best efforts. But being a full-time dad is the best “job” ever, most of the time. It has far exceeded my already high expectations. I would have never been able to understand what I was losing had this pandemic never happened. To boot, consistently getting the really hard reps of solo-parenting has made me a much better father. It’s embarrassing how clueless I was three months ago. What a blessing this has been.

It’s remarkable that so many dads are experiencing this role-reversal at the exact same time. I think it’s an inflection point because a curious thing seems to be happening culturally.

If you’re a parent to young children, I wonder if you’ve noticed this too: being a “working dad” feels a lot more normal. It’s like being a “working mom” was a thing before and being a working dad is finally a thing now too. By that I mean working dads seem to have become a real constituency with a common set of experiences, preferences, and at least some awareness of its existence as a group.

Before the pandemic that mold we were forced into as working dads - and men generally, to some degree - was much more rigid. To be a working dad was to grind at work, not talk about your kids much unless asked or unless you were complaining a bit. You talked about sports, business, alcohol, or politics with your buddies. You help out your partner but you’re still the primary breadwinner and they’re the primary caregiver, and those roles have specific expectations. And maybe you have one relatively masculine and socially expected hobby like working out, brewing beer, playing fantasy football, trying new restaurants, woodworking, a side hustle, or something like that.

And I could go on describing this persona, and I admit that I’m painting in broad strokes - but if you’re a parent of young children you hopefully intrinsically understand the motif I’m outlining. And candidly, the mold of what I feel like I am supposed to be as a young father is frustrating on a good day and sometimes becomes suffocating.

But something feels different now.

Most nice days over the past three months the boys (Bo, Myles, and our pup Riley) and I would go for a walk in our neighborhood before lunch time. Along the way we met a lot of neighbors. That was fun and expected.

I did not expect to meet a lot of other young fathers who were walking with their kids just like I was. Some were also furloughed, and everyone I met actually talked about it openly. Others were still working but were also splitting parenting duties with their partners. I even saw one of my neighbors outside this past week with his baby daughter on his lap, taking a conference call.

And, these neighborhood dads and I, we actually had conversations about what we’re thinking and feeling about as fathers right now, even if briefly. And these conversations with my neighbors about fatherhood had the same kind of easy, open feel as the conversations I hear my wife having with other moms. These were conversations that rebelled against the rigid, masculine, mold I’ve felt restrained by.

This is the first time I ever felt a culture of working dad-hood growing into my day-to-day life. Prior to this pandemic, I only ever talked openly about being a working dad quietly and with my closest friends. Now it’s something that feels more acceptable, probably because this pandemic has given young fathers a shared and significant life experience.

And now that many of us working dads are starting to go back to work and more “normal” activity is happening, I see this change more clearly. And I think it’s for the better. But my call to you, my working dad brethren, is that we cannot put up with some of this BS around being a parent any longer. We have to be done with this foolishness.

When we go back to work, we can’t put up with:

Feeling awkward about taking our kids to the doctor or cutting out of work early to care for our families

Hiding the stresses of being a working dad

Ridiculous policies that don’t provide men (or women) enough paid leave after birth or adoption

Poorly managed teams that have meetings that always run over or go back to back. Our time is too valuable to waste on nonsense

Workforces that don’t have gender diversity, and therefore skew toward a culture of being an old-school boys club

Working all the time and being expected to work during family and leisure time

Work cultures that emphasize useless face time at an office. I’m not even convinced that most companies are managed well enough to see a measurable difference between co-located teams and remote teams

There’s so much more we shouldn’t put up with; these are only a handful. Especially now that we understand being working fathers so much more intimately than we did three months ago, we should hold ourselves and our companies to a higher standard.

And the best part is, refusing to tolerate this foolishness is not just the right thing to do or a timely topic, I think it’s very possible that if we hold ourselves and our teams to a higher standard it’ll lead to higher profits, happier customers, and thriving teams.

Working moms have been pushing this agenda for some time, and I think it’s time for us join them in a big way.

Simple over SMART

Simple is not only enough, simple might be better than smart.

I like New Years Resolutions, But for most of my life I wasn’t very good at achieving them.

This year, for the first time ever, I remembered what my resolution even was (get a new job) at the end of the year and I actually achieved it.

Why?

It was simple enough to actually remember. There was also only one.

It was specific. I could actually know when the goal was achieved. When my paycheck had another company name on it, I was done. Boom.

It was really important. It took a long time to convince myself, but I realized that I needed to make a change.

It was urgent. Even though it took a long time, I felt compelled to work on it every day and week.

SSIU is not a catchy acronym like SMART. But in my personal experience SMART goals are so complicated to write well, I often don’t remember them after a week.

In fact, an acronym might even be unnecessary in the first place. If a goal is simple, the specificity, the importance, and urgency take care of themselves.

Simple is not only enough, simple might be better than smart.

—

Friends,

If you follow my work you might be interested to know my resolution this year: publishing this book. It’s drafted, but it still needs to be transcribed, edited, laid out, and shared.

If you have advice or encouragement on how to do this, I would love to talk with you.

Integrity-first Management

A simple idea for how to run a company.

It’s been refreshing to see the narrative of “maximizing shareholder value” be influenced by other ideas, like: triple bottom line, shared value, positive business and others.

These ideas are hybrids, balancing the interests of customers, owners, employees, and society.

But what if we went further and didn’t treat these interests congruently?

Instead, what if we simply refused to consider strategies that were unethical, irresponsible, or harmful? After first applying the hard constraints demanded by our character and integrity, we could then freely maximize shareholder value. At that point, maybe we ought to.

The problem is, that requires a lot of integrity and a lot creativity. I think it’s worth it, and something we owe to each other now, and to future generations.

I suspect that there are already many people that are quietly running companies this way. Even though running businesses in this way is hard, I think we can do it.

Afterall, the only two nearly renewable resources are sunshine and human creativity. And sunshine makes the difficult challenge of acting with integrity much more pleasant.

Timeless

What makes something timeless?

The Mona Lisa isn’t just a painting of a woman smiling. A pair of Levi’s isnt just a pair of pants. Shakespeare didn’t just write some plays. Amazing Grace and Ave Maria are just some spiritual songs. The Gettysburg address wasn’t just a speech.

None of these are particularly fancy. There are plenty of comparables in their respective domains, too. And yet somehow these things are different. Not cool, not hip, not sexy, but still something special.

They tapped into something deeper than trend, or the zeitgeist. They are simpler. They have stories about them that transcend the trivial concerns of a single generation. They exhibit outstanding craftsmanship.

They are timeless.

A marriage, a family, a company, a team - even a blog. These could all be timeless too. But to be timeless, we must give up trying to be a lot of other things.

The question that changed my life

The nuance is transformative.

What I do as a father is not glamorous.

I give Bo food. I carry him around. I make sure he cleans up messes. I wipe up urine. I wash his dishes. I put on his socks. I read him stories. I keep him from jumping off things. I give him hugs and kisses. I make him use his words. I comfort him when he’s upset. I take him with me to the grocery store. I wipe his tush.

What I’m trying to do as a father, is a much different question. I’m trying to help him feel loved and safe. I’m trying to help him learn to be a good person. I’m trying to help him discover some of life’s joys like reading, friendship, love, family, service, and faith. I’m trying to give him a model of how to treat his spouse, his parents, and his children. I’m trying to create the space and courage for him to be himself.

What we do and what we are trying to do are radically different questions. The first question (what we do) is about the very specific actions we take, the second question (what we’re trying to do) is the generous, positive impact we hope our actions make for those we seek to serve. In organizations - whether it be companies, families, churches, community groups, or teams - the nuance here is often lost.

And what a tragedy that is.

Because for a team to be high-functioning both questions have to be answered, very specifically. More often than not, the question of what we’re trying to do is what’s forgotten. Which is a damn shame, because that’s the question of the two that motivates and inspires us to be the best versions of ourselves.

But answering that second question, I admit, is very difficult because it requires us to imagine a future that does not yet exist. I’ve found, however, that once you struggle through the nuance it is absolutely transformative.

The art of being adamant about small, but transformative things

What’s something that is worth being adamant about?

One of the things I do very deliberately when I am in public is to pick up single bits of trash I come across. I want the sidewalk to be clean And it’s really very easy.

I always hope that someone notices me doing it. I don’t want credit, but I will admit that I feel nice when the act is appreciated. What I do want people to think having a clean sidewalk is normal and caring enough to pick up a single piece of trash to keep it clean is normal, too.

A key question is: what critical mass of a community needs to be adamant about something for the culture to change? Some folks say 3.5% and others say 25%. It seems to depend on what the objective is, like whether you’re spreading an idea or a behavior.

The good news is, both estimates are much less than 100%. From what I’ve gathered and observed, the key is to be adamant about doing the very specific action for it to catch on.

These are worth being adamant about, to me. If we had even 3.5% of the population doing these, we would have a very different community:

Picking up a single piece of trash

Saying “hi”, “good day”, or nodding to people that pass

Running or riding a bike through the neighborhood

Shoveling snow promptly

Keeping grass cut (though I admit to slacking on this)

Saying thank you when I am a customer

Asking emotional questions and sharing emotional stories when asked

If a small group of people are adamant about something, it tends to happen. This makes it really important then to be adamant about something. And carefully considering whether those things we go to the mat for make things better, or make things worse.

A question for the comments: What’s something that is worth being adamant about?

—

On September 30, I will stop posting blog updates on Facebook. If you’d like email updates from me once a week with new posts, please leave me your address, pick up the RSS feed, or catch me on twitter @neil_tambe.

How To Actually Build A Culture - What I've Learned

Don't mimic a different organization's culture, evolve to one based on your business environment.

Most companies I’ve come across are copycats. Their founders and executives look at how other companies do business and mimic the work environments (a composition of a company's habits, rituals, and practices) they like. In effect, they try to copy the culture of organizations they’ve seen before. On it's face, this is a fool's errand because most people haven't been in a high-functioning organization or team to begin with.

Even worse, it's reckless to mimic a different company's work environment, even if it is high-functioning. Why? Because those practices might not work well in a different business environment. Instead, the curators of a company’s culture – which are most often its founders and executives – should evolve their company’s work environment to fit the context in which they operate.

Animals and plants have been doing this for centuries. Camels and cacti, for example, have evolved to deal with water scarcity because they live in the desert. Bears have lots of fur and hibernate in the winter because that's what they need to survive in a colder climate. Animals and plants evolve to their habitat.

Companies, or even individual teams, should do what animals do – evolve their work environments to fit their habitat. Just like it doesn’t make sense for a camel to try to mimic a bear, it doesn’t make sense for a company in one “habitat” to mimic the culture of a company with a different business environment.

What's My Company or Team's Habitat?

I’ve found that the answers to two questions give reasonable insight to what a company’s “habitat” is and what that habitat requires of its work environment. After all, if you’re in a position to shape the culture of a company or team, it’s hard to do that without what your business environment requires. Here are the two questions:

What do your customers reward – execution or innovation?

What is the operating context in your market niche – simple & stable or complex & dynamic?

These two questions yield 4 basic “habitats” that each require a company or team’s work environment to emphasize different attributes - Coordination, Discipline, Motivation, or Learning:

(For help on how to determine your company or team’s habitat, click to this supplementary post).

How to Evolve A Culture

Correctly identifying your company or team’s habitat is one challenge, and evolving its culture to fit that habitat is quite another. I think the way to do this is choosing something – a moment in the day, an interaction, an artifact – and experimenting with it. Some colleagues and I put pen to paper on this concept in Work Environment Redesign.

I’d recommend experimenting with something small and mundane that’s done a certain way because “it’s the way we’ve always done it.” My favorite example is reimagining standing meetings. Here’s how the agenda of a standing team meeting could look for companies and teams in different habitats.

Lot's of little things can be evolved to fit a company's habitat - annual reports, branding, how customers are greeted, physical space, how recruits are interviewed, etc. Even if you only experiment with only one or two aspects of your work environment at a time, you’d be surprised how much your company or team’s culture can evolve even in a few months.

One more nuance I'd like to point out is that this model implies that a company's culture shouldn't be permanent. If a company's business environment changes, so should its work environment.

If you have stories or experiences to share with others about evolving your company or team’s work environment and culture – I’d love to hear about them in the comments (or a guest post)!

How Cultures Form, Part I - Frameworks for Culture

What is a culture? lt's surprising how difficult and inconsistent definitions of "culture" are. I mean it in the context of organizational culture, and I'll put forth one I found here, which is:

"A set of understandings or meanings shared by a group of people that are largely tacit among members and are clearly relevant and distinctive to the particular group which are also passed on to new members (Louis 1980)."

There's also a widely accepted model from Schein which breaks culture into three levels: artifacts, beliefs / norms, and assumptions. I pulled a nice graphic explaining this from a blogger named Patrick Dunn. You can see his original post here:

But, the more important question here is, how do cultures form? Or, here’s a link to some thoughts on a different (but relevant) question: how does one actually build a culture?

How Cultures Form I've done a bit of research on the question of how cultures form and have done my own thinking on the matter. How cultures form is surprisingly simple. Generally speaking, it's a three-step process.

I use the term cultural idea to include representations of culture at any level of Schein's model - artifact, belief / norm, or assumption. Think of a cultural idea as a value, a physical object, belief, a way of thinking, language, or anything else that represents a culture...it's a broad, inclusive term:

Express Cultural Idea - The process starts by someone expressing an idea through some medium...whether it is a belief, an object, an action, a document etc.

Share Cultural Idea - The process continues when cultural ideas are shared within the group where the culture is forming. As more people accept and internalize the cultural idea, the culture grows

Form new Cultural Ideas - Once a cultural idea is expressed, people form new ideas which contest or reinforce other cultural ideas. Once shared, the process starts again. With each cycle, prevailing cultural ideas become reinforced. The ideas that get reinforced the most become part of the culture

Note that this process of Express -> Share -> Form has to be isolated from other cultures. Without some means of isolation or boundary between the group in question and others, cultural ideas wouldn't be able to reinforce each other. In Detroit this is a geographic boundary from say New York, or Chicago. Unless there's some separation from other cultures, no unique culture can form.

Also, note that for cultures to form, there's activity or structure required to move from step to step. I'll call these mechanisms Interaction Channels. These interaction channels provide the human interaction needed for cultures to form. In other words, if culture doesn't form in a vacuum and requires interactions between people, then there has to be different mechanisms to interact with other people. The mechanisms in these channels different types of interactions required for cultural formation: transmission of cultural ideas, dissemination of cultural ideas, and reflection on cultural ideas.

Transmission of cultural ideas - ideas have to get out of peoples' heads to be able to form and shape culture. Some example mechanisms for transmission are: blogging, social events, art, conversations, strategic plans, interactions in public spaces, mission statements, etc.

Dissemination of cultural ideas - ideas have to be amplified to reach the critical mass of awareness to be able to influence culture. Some example mechanisms for dissemination are: mass media, press events, word-of-mouth, social media, community organizing, etc.

Reflection of cultural ideas - ideas have to evolve and refine for some ideas to reinforce the prevailing culture. In other words, people can express ideas that they never reflect on and form in their heads. Some example mechanisms for reflection are: journeys into nature, community dialogue, third spaces, social media, and story telling.

Interaction channels could also take a few forms. Check out a list (e.g., rites, rituals, gestures) here.

How To Form Culture in Detroit - A Teaser So, to form a culture in Detroit (or anywhere) it's is simple and complicated as fostering these expressing, sharing, & forming behaviors, and, building up interaction channels.