How Cultures Form, Part I - Frameworks for Culture

What is a culture? lt's surprising how difficult and inconsistent definitions of "culture" are. I mean it in the context of organizational culture, and I'll put forth one I found here, which is:

"A set of understandings or meanings shared by a group of people that are largely tacit among members and are clearly relevant and distinctive to the particular group which are also passed on to new members (Louis 1980)."

There's also a widely accepted model from Schein which breaks culture into three levels: artifacts, beliefs / norms, and assumptions. I pulled a nice graphic explaining this from a blogger named Patrick Dunn. You can see his original post here:

But, the more important question here is, how do cultures form? Or, here’s a link to some thoughts on a different (but relevant) question: how does one actually build a culture?

How Cultures Form I've done a bit of research on the question of how cultures form and have done my own thinking on the matter. How cultures form is surprisingly simple. Generally speaking, it's a three-step process.

I use the term cultural idea to include representations of culture at any level of Schein's model - artifact, belief / norm, or assumption. Think of a cultural idea as a value, a physical object, belief, a way of thinking, language, or anything else that represents a culture...it's a broad, inclusive term:

Express Cultural Idea - The process starts by someone expressing an idea through some medium...whether it is a belief, an object, an action, a document etc.

Share Cultural Idea - The process continues when cultural ideas are shared within the group where the culture is forming. As more people accept and internalize the cultural idea, the culture grows

Form new Cultural Ideas - Once a cultural idea is expressed, people form new ideas which contest or reinforce other cultural ideas. Once shared, the process starts again. With each cycle, prevailing cultural ideas become reinforced. The ideas that get reinforced the most become part of the culture

Note that this process of Express -> Share -> Form has to be isolated from other cultures. Without some means of isolation or boundary between the group in question and others, cultural ideas wouldn't be able to reinforce each other. In Detroit this is a geographic boundary from say New York, or Chicago. Unless there's some separation from other cultures, no unique culture can form.

Also, note that for cultures to form, there's activity or structure required to move from step to step. I'll call these mechanisms Interaction Channels. These interaction channels provide the human interaction needed for cultures to form. In other words, if culture doesn't form in a vacuum and requires interactions between people, then there has to be different mechanisms to interact with other people. The mechanisms in these channels different types of interactions required for cultural formation: transmission of cultural ideas, dissemination of cultural ideas, and reflection on cultural ideas.

Transmission of cultural ideas - ideas have to get out of peoples' heads to be able to form and shape culture. Some example mechanisms for transmission are: blogging, social events, art, conversations, strategic plans, interactions in public spaces, mission statements, etc.

Dissemination of cultural ideas - ideas have to be amplified to reach the critical mass of awareness to be able to influence culture. Some example mechanisms for dissemination are: mass media, press events, word-of-mouth, social media, community organizing, etc.

Reflection of cultural ideas - ideas have to evolve and refine for some ideas to reinforce the prevailing culture. In other words, people can express ideas that they never reflect on and form in their heads. Some example mechanisms for reflection are: journeys into nature, community dialogue, third spaces, social media, and story telling.

Interaction channels could also take a few forms. Check out a list (e.g., rites, rituals, gestures) here.

How To Form Culture in Detroit - A Teaser So, to form a culture in Detroit (or anywhere) it's is simple and complicated as fostering these expressing, sharing, & forming behaviors, and, building up interaction channels.

The Magic of Third Spaces, Written From Detroit

I am sitting in a coffee shop and the world is abuzz around me. By now, it's cliche to spend a morning camped out at Great Lakes Coffee - a less than three year old bar and coffee shop in the heart of Detroit's Midtown neighborhood - because it's a well trodden establishment for the city's burgeoning "creative class." But that doesn't make it any less impressive. There are medical students studying in their scrubs, and older men and women conducting meetings in suits. There is a gentleman in a beanie who is wearing a long-sleeved t-shirt with the emblem of a plumber's association. There is a college student in headphones eating Sun Chips. Behind me, the guys who tried to bring the X-games to Detroit and who are launching the ASSEMBLE festival are having a working session. All these people are certainly not a full representation of Detroit's residents, but, it's much more so than most establishments.

This ability to gather, to learn, to work...to dream amongst other dreamers and serendipitously meet them is the magic of the third space.

These semi-public spaces are essential for the development and creation of knowledge, the sharing of ideas and relationships. Third spaces like coffee shops have the openness to bring disparate people into proximity, but have the structure to be focal points of activity. They are respites from the corporate jungle just as they are offices for bootstrapping entrepreneurs and students. They are mixing bowls which mash up different kinds of people with different kinds of ideas - a necessary ingredient for creativity and innovation. Third spaces are community centers, laboratories, and parlors all at the same time. They just happen to serve coffee.

At the same time, these third spaces are not Detroit's savior. There is certainly a carrying capacity for how many third spaces can healthily exist in a city, and they don't create many jobs. They are not accessible to all, either, because not everyone can afford designer coffee or membership fees. But they are a necessary part of a city's social fabric, that creates the right condition for learning, sharing, creativity, and entrepreneurship to occur.

What I hope is that the people sitting in these coffee shops and other third spaces are dreaming about more than just opening other coffee shops and other third spaces. I hope they are thinking about new products and services, philosophies and expressions, businesses and innovations.

And in Detroit, I think we are.

Reimagining Business School Rankings

From what I can tell, rankings are hugely important to the staff and administration of business schools. Rankings, after all, are what prospective students often use to judge the quality of a business school and the value of the $100k+ they spend to complete their graduate education. The one part of business school rankings that aren't really talked about - which I'd argue is the most important - is the methodology of the rankings. Looking at the methodologies is important because different people value different things about business school, so the ranking is only valuable if you value the same things as the people who created the rankings. It's funny that there's little discourse about the formulas for the rankings, no? In fact, I suspect that people talk considerably more about the College Football Bowl Championship Series methodology than they do about the methodology of business school rankings.

After looking into the rankings' methodologies, here are some of the criteria I found. Each ranking uses different combinations of criteria, of course:

- Salary of the graduate's job 3-5 years after graduation

- What recruiters think about the school

- What other business school faculty think about the school

- What students think about the school

- Rates of faculty publishing in major journals

- Rates of graduates being placed into jobs after they graduate

- GMAT / GRE / GPAs of incoming students

- Diversity of the class

- Quality of alumni network

For more details, here are the links to the methodologies of various rankings: The Economist, US News, Financial Times, Forbes, Businessweek

What I propose is that there are other metrics that matter, that could better demonstrate the quality of the school and give a flavor of the priorities of that school's administration. Here are some measures I'd be curious about...ones that I'd consider measuring if I were making the ranking:

- Percentage of students who go to jail (this is what sparked the idea for this blog post, I was talking with two classmates about this)

- Percentage of students who become c-level executives

- Number of VC dollars raised per student, number of startups launched per student

- Number of students who are single at some point during their studies who end up marrying classmates or alums

- Percentage of graduates who feel happy / fulfilled in their work 5 and 10 years after graduation

- Percentage of graduates who enter non-profit or public service careers for a period of time within 5 years of graduation

- Effectiveness of graduates as rated by their peers and/or subordinates at work

To assess whether a business school is doing a good job preparing its graduates for business careers, we ought to have a broader set of measures. I wonder what the rankings would looked like if we prioritized holistic measures in addition to or in lieu of what the rankings currently measure.

Jargon vs. Slang - And How We Treat Them Differently

Let me start by saying this post is an observation. I don't intend to make an explicit point. That said, I think this is a topic that many regular readers of this blog have an interest in. With that in mind, I invite you to share your opinion or add your observations in the comments. If you like, I'll even update the postscript of this post with your text (anonymously if you like). If you want to add your story to the text of the post, e-mail me: neil dot tambe at gmail dot com.

An observation: we evaluate jargon and slang differently

I was out with some friends, and because most of them are former (or current) teachers in Detroit we often discuss topics related to education or their students. This past weekend, we started discussing some of the slang used by Detroit students. Here are the highlights:

- "You're telling a story" or "You're boostin" = You're lying

- "That [shirt, or something else someone is wearing] is crispy" = That [shirt, or something else someone is wearing] looks really good

- "Why are you finessing my shirt?" = Why are you stealing my shirt?

- "What up doe" = YES, I AFFIRM WHAT YOU ARE SAYING AND IT IS GREAT, or, what's up?

For a moment, forget about any improper use of grammar embedded within these phrases (which I might add, I like some of them a lot...they're fun). Focus on the slang. In contrast, here are some highlights of the corporate jargon I heard (and unfortunately used, sometimes) as a consultant:

- "We need you to take ownership of that work" = We need you to be responsible for that work

- "We're boiling the ocean" = We're attempting to solve more problems than we have the capacity to handle

- "We will start with the marketing piece, then continue with the finance piece" = We will start with the work we need to do related to marketing, and then continue with the work we need to do related to finance

- "I'll reach out next to touch base so we can find a time to connect about best practices we can use for the project" = I will contact you so we can meet to talk about the advice you have (based on your experience) that we can apply to accomplish the goals of this project

Both sets of phrases - the slang and the jargon - are equally contrived and imprecise. If anything, the jargon is more vacuous and sterile. To be fair, the jargon and the slang carry meaning within the communities of their use; the words do give common understanding of an idea.

What is interesting, however, is that we generally perceive the slang as an indication of immaturity and the jargon as professionally acceptable (albeit annoying). We judge the slang and assimilate the jargon, even though the contexts of usage are similar.

That's interesting, isn't it?

Measuring Social Value, Part II – A Framework For Measurement and Evaluation

In the previous post of this series, I proposed that we don’t have a sound theoretical framework for understanding forms of non-economic value creation. Because we don’t have a theoretical framework for understanding non-economic value (e.g., social value) we don’t have tools to measure and assess our efforts to create it. In turn, we aren’t very good at addressing social problems. As I mentioned in the post, Business Must Do Good, social value is all about happiness. So any framework for understanding social value must aim to explain happiness, which I’ll call “welfare” in this post. For those of you who are economists, you can think of welfare as an analog for consumer and producer surplus.

For now, I’ll go straight into a work-in-progress framework for understanding social value (i.e., welfare), leaving out much of the theoretical underpinnings. I’ll save those for a subsequent post. Needless to say, it’s a little complicated. There are several types of social value (e.g., physical health, intellectual engagement, social engagement, emotional health, etc.). For the sake of introducing the framework, I’ll focus on physical health.

A Framework for Social Value Creation

What’s different about social value, is that it’s not always best to maximizing or minimizing a certain quantity – like some abstract measure of physical health, like resting heart rate or weight. For social value, it’s instead important to be in balance between extremes. Moreover, it’s not always about absolutely quantities either, sometimes welfare is derived from comparisons between an individual’s level of welfare versus another person, versus their aspiration, or versus their perception of their level of welfare.

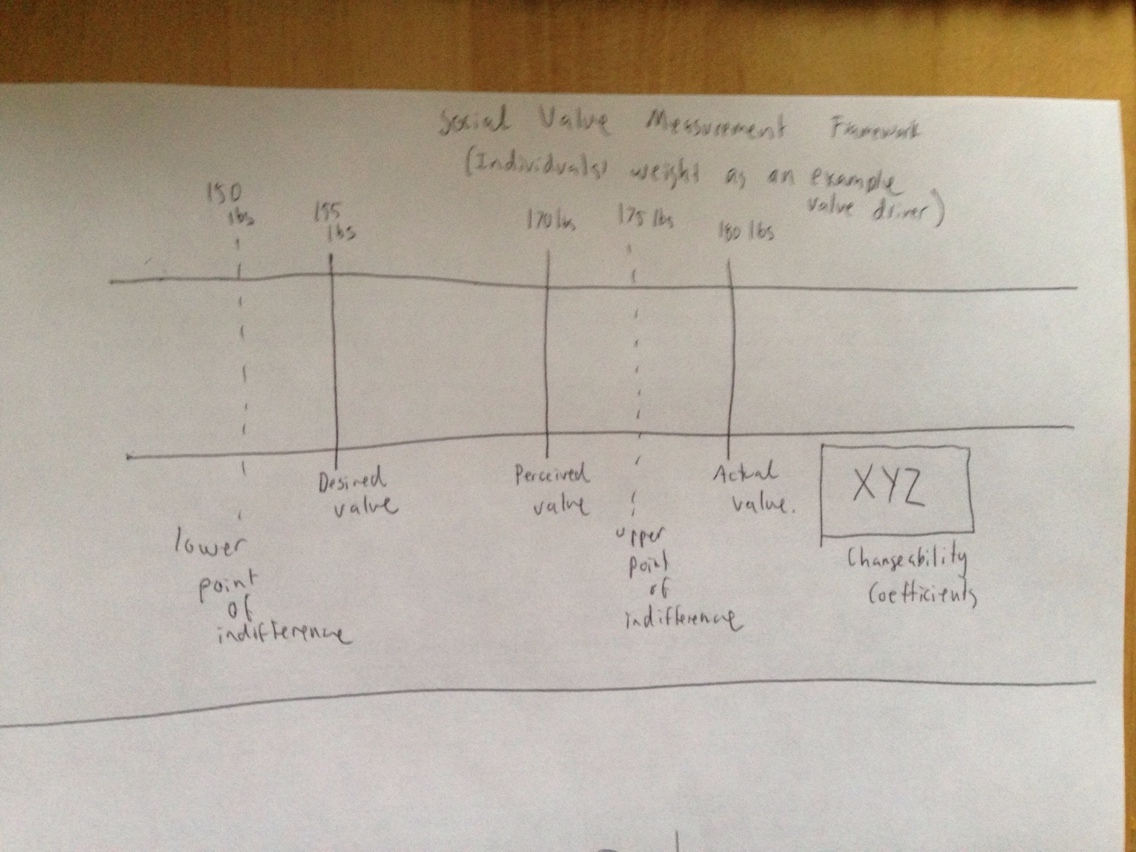

These observations are the basis of this framework, which is how I propose we conceptualize social value. I will explain each part of it in turn:

Overview: This is a horizontal bar and not a wedge, for a reason. I don’t thin social value should be measured implying more is better than less, it’s all about meeting expectation, being in balance, and having equity between people…because that’s what makes us happy. This bar is a simple way of plotting out certain types of information in a cohesive way, and what is important to interpret is how these quantities of welfare relate to each other.

The bar as a whole is a range of possible levels of welfare for some value driver, in the realm of physical health maybe it’s something like resting heart rate, blood pressure, weight, or some quotient between the three.

Points of indifference: I have plotted upper limits and lower limits of indifference. By this I imply there are values where it doesn’t matter so much if one has more or less welfare. Take resting heart rate or weight for example, if you’re in a certain range you’re considered healthy and it doesn’t really matter if you’re within that range. When you fall outside that range, it’s not a great thing.

For individuals, the interpretation tactic here would be to see whether people fall inside our outside this range of indifference. For societies, you could evaluate – in aggregate – what the distribution of people across the value driver is…say in a histogram. You could also look at whether the range between the indifference points is increasing or decreasing.

Desired Point, Actual Point, and Perceived Point: Think of this using the example of weight. On this horizontal bar, different people would have different desires of where they would want to be, where they actually are, and where they perceive they are. Plotting these points would provide insights on whether people are actually happy because you could evaluate the gaps between these points.

For individuals the interpretation tactic would be to look at the gaps between desired points, actual points, and perceived points because they would give some indication on how happy that person is (because a lot of what makes us happy is whether we are getting what we desire. For societies, you could aggregate and look at centrality and variances measures for these values and the distances between them.

Ability and Perceived Ability to Change Actual Point (Changeability Coefficients): A final component that affects our happiness is whether or not we have the agency to change our actual life outcomes. Again, think of weight as an example – if we think we can’t change our weight or actually can’t change our weight and we want to, it make us unhappy.

You’d have to measure this as some sort of coefficient or rate and represent it in some way (explicitly or maybe changing the color of the graph to represent different coefficients). You could measure this at the individual or aggregate level.

Next Steps

After explaining this framework, I know there are at least two open questions. I will attempt to slowly build on this model by addressing them in future posts. They are:

- “Weight and blood pressure – the examples you gave – are only two of many, many, things that affect happiness and social value…what types of things would you measure?”

- “Let’s say you could determine different types of things to measure. How would you actually collect and analyze the data?”

I also invite you to challenge my ideas a lot. This is a huge idea and I want to work collaboratively to get it right. If we, together, do get this idea right…it sincerely and wholeheartedly believe it could provide the foundation for groundbreaking work.

Once I’m able to articulate the complexities of social value, I’ll move on to Civic Value and Spiritual Value.

Measuring Social Value, Part I – Understanding The Complexities of Non-Economic Value

You Can’t Manage What You Can’t Assess (And Measure) A few months ago I introduced the notion that Business Must Do Good. Urban Innovation Exchange even picked up the post. In that post I proposed that there are four kinds of value that can be created: economic, social, civic, and spiritual.

These types of value creation are inevitable in the organizational world. As businesses, governments, NGOs, religious organizations, and others consume resources to operate, they will inevitable create and destroy value. Some of that value will be in each of the four realms I have described: economic, social, civic, and spiritual.

We can’t manage value creation in each of these realms unless we assess them. Without some form of assessment, categorization, and measurement we will not be able to proactively take steps to create or destroy value in each of these realms. As a result, even though me may want to create social, civic, or spiritual value, we won’t be able to intentionally.

In short – you can’t manage what you can’t assess (and measure). And by that I don’t mean that we have to measure social, civic, or spiritual value and convert it into a dollar value. In fact, I think that’s a foolish exercise that can’t be done. This idea is so important (and so misunderstood), I’ll focus on the relationship between economic and social value in a subsequent post.

Since we want to manage (and foster) the creation of social, civic, and spiritual value, it’s absolutely essential for us to assess and understand it. This is to say that we need to measure value.

Many have failed in attempting to assess non-economic value. Now, I’d like to present a new approach.

Better Approaching the Assessment of Non-Economic Value

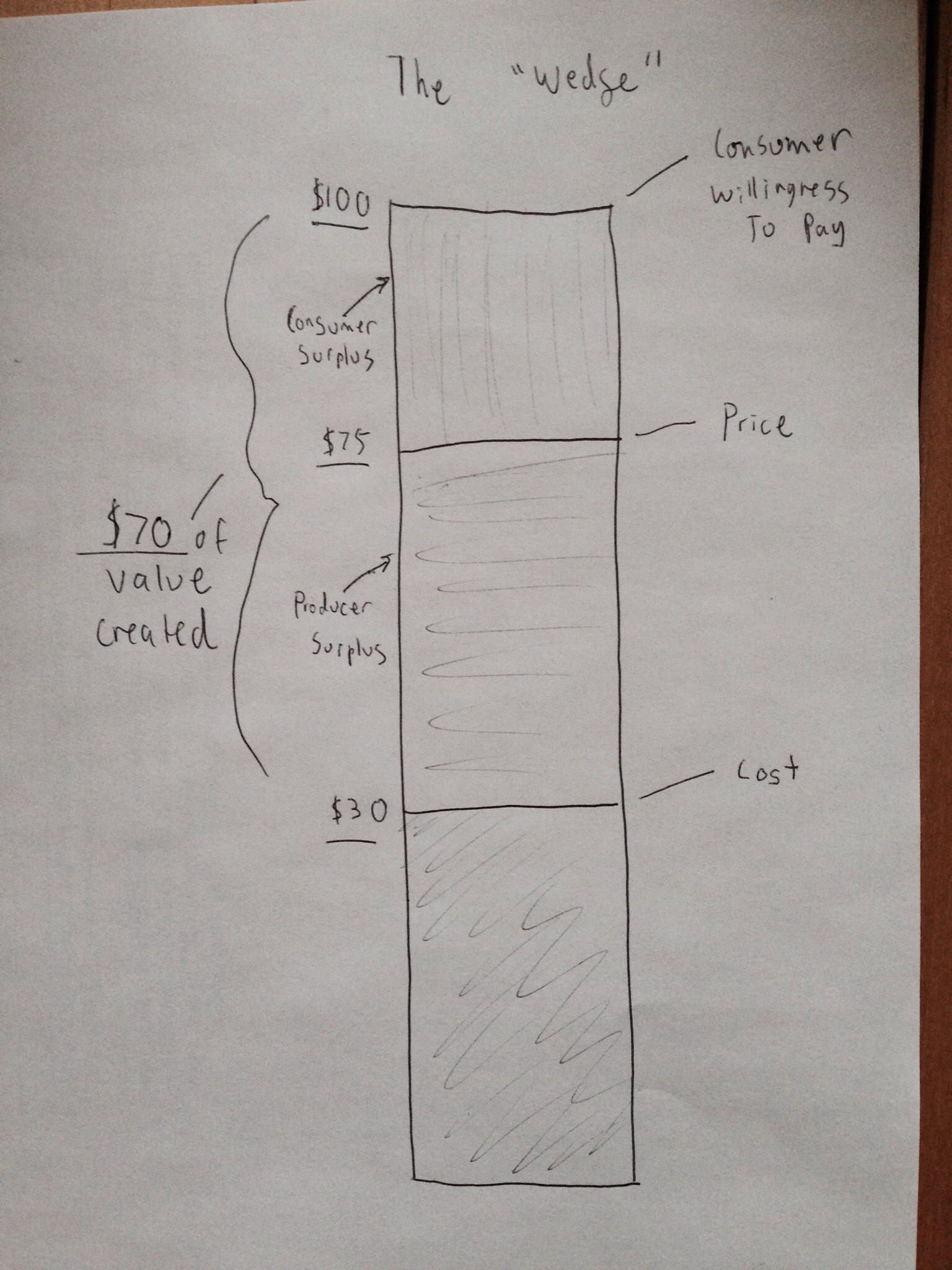

We have some really good tools for understanding economic value. If you take an introductory strategy class in business school, you’ll quickly learn about the wedge as a framework for understanding value.

In short, economic value is the difference between how much a consumer is willing to pay for something minus its cost. Here’s a visual explanation, it’s called the “wedge”:

Everything in business tries to affect these parts of the wedge to create more value. Because creating (and capturing) value is the goal, there are all sorts of things to measuring each aspect of this diagram, people study this stuff like crazy – whether it’s how to optimizing pricing to figuring out how to accurately define how much a customer is willing to pay, and more, not to mention oodles of ways to measure costs.

The point is this: because managers measure willingness to pay, price, and cost – and study it like crazy – they are able to analyze what’s preventing them from creating value and change something to create more value. The tools of business require measurement to improve performance. Business tools, it turns out, are derived from this “wedge” because it’s a simple framework for defining economic value.

The Wedge Doesn’t Work For Non-Economic Value

The wedge, unfortunately, doesn’t translate well to non-economic value. Happiness (the aim of social value) doesn’t have traditional "costs" and it’s really hard to measure happiness in terms of dollars, nor does it have “prices” in the same way as economic value.

I propose that this is why we're swimming around aimlessly when it comes to measuring non-economic value: we don’t have a simple way of understanding what social value is. We need a novel representation of social value – like the wedge – except for social, civic, and spiritual value. Once we have those, we can build more sophisticated tools to understand and measure non-economic forms of value.

For the past few months, I’ve been questioning, tinkering, and exploring how to develop a framework for non-economic forms of value. I started with social value. Read the next post in this series to discover and provide feedback on what I’m coming up with.

Detroit Doesn't Have a "Culture" (sort of)

While I was a research fellow at the Center for the Edge working on this paper, two of the most interesting documents I came across were from Netflix and Valve Software. They were in essence, company culture manifestos. What’s important about them is that these documents are very comprehensive and they are written down. These qualifications – that the documents are comprehensive and written down – is important to note. A culture doesn’t matter unless you can describe it specifically, because if you can't it implies that the culture is weak, coincidental and/or inconsistent across the organization. Coincidental cultures, if you will, don't stand the test of time and are more like fads. What's the point if a culture isn't distinct and enduring?

(Here’s a teaser for later in this post – by this definition, Detroit likely doesn’t have a culture because it's not consistent across the city)

I’ve had the privilege of presenting to a few government and corporate executives in the past few weeks. Culture has come up a few times and it’s not surprising – organizations everywhere are trying to build culture because leaders are realizing that people management (the umbrella category for things like culture and talent) is a sustainable competitive advantage.

But I think a lot of organizations have the wrong approach when it comes to organizational culture. Instead of building and evolving what they have, and create something unique to their organizational challenges and strengths, they try to copy someone else’s culture. The tech sector is often the target of this mimicry, whether it’s copying the practice of rotational programs or having snacks on every floor.

The 1993 Disney film Cool Runnings (which is especially timely because the Olympic winter games are currently occurring in Sochi), offers a parable for why it's important not to mimic someone else's culture.

Recall the scene where the bobsled team is in the Olympic village preparing for their big race. Derice makes reference (per usual) to being like the Swiss sled team. And after an exchange Sanka replies exclaiming that the team won’t be able to perform at its best unless they stay true to what they are: Jamaican.

This lesson also applies to organizations. Organizations can’t do their best unless they stay true to who they are. It takes too much effort to try to be something your not, and that’s effort that can’t be accomplishing goals. If you don't act like yourself it's also hard to be confident - you never know if someone is going to pull the curtain away and reveal you are a fraud.

So when I see companies trying to “build culture” and achieve results by copying the practices of what others are doing, I think they are missing the point. What matters about culture building is doing things that represent who you are, and implementing programs that affirm that identity, not transplanting a practice from another company and forming an identity around that. Copying someone else's culture just isn't sustainable.

I'd argue that being able to articulate a culture comprehensively in writing is a good indicator that the culture is distinct, authentic, and sustainable. If it's not possible to do so, the culture probably isn't sustainable.

Detroit’s Culture

First let me say, there’s no document (that I can find) that articulates Detroit’s culture like the Netflix or Valve Software documents that I linked to above. But that’s not the point. The point is whether one could document Detroit’s (or any other organization’s) culture if they tried.

In Detroit, I don’t think we could document a single, cohesive, culture even if we tried. Detroit has at least two worlds (this is actually something my friends and I talk about a lot) But, I think this is a point reasonable people could disagree about. If you disagree, I welcome you to add comments on this page and list out your articulation of Detroit’s culture.

But for a moment let’s assume that Detroit does have a single, cohesive culture and identity. If that’s the case our culture certainly not documented or explicitly identifiable via some others medium. We should try to do this.

Documenting our cultural norms and practices would allow us as Detroiters to argue about what is good and bad about our culture and identify elements to evolve. We could put in systems to amplify the culture (an example of this is type of system would be the Andon cord at Toyota or Google’s CEO signing off on every single hire at the company). We could put in policies to police the parts of the culture that are destructive. It would also be a way for people outside Detroit to get a sense of what Detroit is truly like.

Most importantly though, having a strong culture (that’s identifiable) helps with decision making. When weighing several options – say for how to deal with influxes of investment and development downtown – having identifiable cultural norms helps guide how decision makers should weigh the options. As an example, If equity were a prominent part of our culture, that everyone agreed to, decision makers might choose a less lucrative investment if it was more fair to existing residents. Cultural norms are a decision-making heuristic of sorts.

Now, it’s possible to run an organization (or a city, like Detroit) without a common set of cultural norms and values. There's nothing wrong with having a community of sub-cultures, it can work. The downside is that it leads to conflict. Look at San Francisco and the opposition to tech company shuttles and the creative class in the city. Because of different sub-cultures (that have conflicting values) existing in the city, it is leading to cultural clash.

With this example in mind, we can have distinct sub-cultures without an overarching common set of values, but we will have to resign ourselves to the fact that there will be conflict.

I think there are real benefits for creating an environment where culture can develop. And that’s exactly how I think it happens…you create environment for culture to occur and it develops on its own. In the long-term (at best), individual agents can only influence culture, not prescribe it.

This emergent phenomenon doesn’t happen in places where there aren’t connections across communities and inclusive participation of the entire population. So if we want to develop a unified culture in Detroit, that’s what we should do, make institutions and public dialogue inclusive.

Tackling the unsexy (but game changing) policy issues

I attended a great event last night, put on by the good folks at ASSEMBLE and Chad of Urban Social Assembly. The troupe brought in Vishan Chakrabarthi of SHoP Architects in New York to speak about the views he articulated in his excellent book titled "A Country of Cities." In his talk, Vishan highlighted how national policies have shaped how urban and suburban landscapes have developed in America. The existence of the mortgage interest tax deduction and the construction of interstate highways, for example, made it cheaper and easier for suburbs to grow. I never shy from asking a smart person a question, so I probed the folks onstage (by this point, Craig Fahle was leading a panel discussion with Vishan and a few Detroiters) about whether cities with transit-oriented densities could develop without state or national policy change. Are there any levers cities can pull unilaterally?, I asked.

All the panelists gave interesting answers, including Vishan, but the visiting urbanist also challenged the premise of my question. Millennials, he contended, shouldn't always shy away from big systemic issues and shouldn't balk at the opportunity to shape far-reaching public policies. A lot of these system-wide policies, he argued, are worth tackling because they fundamentally change how the problem can be solved. Millennials shouldn't shy away from these big policy debates because they are hard, complex, and are unlikely to provide instant results.

He's right.

A lot of policies are so deeply seeded in how we conduct business in the US, that they constrain the possible outcomes in the system. Take the mortgage interest deduction - a subsidy on the order of hundreds of billions of dollars a year - as an example. If we're putting intense downward pressure on prices for owning homes, of course suburbs will grow. There are many other unsexy issues like the mortgage interest deduction that have huge impacts on how things work in America. If we don't change some of these things, we may never move the needle on solving some of our country's most difficult social challenges - the ones that millennials claim to desperately want to solve.

As a generation, we millennials crave "positive change" which "leaves an impact" on the world and "makes it a better place." And that's great. But I think we're missing something important if we don't work on some of these foundational issues similar to mortgage interest deductions - like money in politics, emphasis on quarterly earnings and shareholder value maximization, gerrymandering, due process of law, infrastructure investment, budget reform, tax reform, and others.

Maybe the work of our generation should be to tackle unsexy, but game-changing, institutionally-driven, systemic policy changes so our children can do the explicitly impactful work we always dreamed of. Maybe some of us should trade social entrepreneurship for system design. If we did, maybe institutions like governments, markets, and courts would function better in the first place and make some of the gripping social problems we face today less overwhelming to address.

Is Social Entrepreneurship a Middle Class Opiate?

Tunde, a good friend of mine, raised an important question in response to one of my previous posts - Bow Ties, Crazy Socks, and Hip-Hop: Tactics for Successful Intrapreneurship - which I have been mulling over for the past two weeks. He posited: isn't social entrepreneurship just an opiate for the middle class? Though it's possible to dismiss this question as outlandish, I think it mirrors an important debate in the Social - X (fill in the "X" with impact, intrapreneurship, entrepreneurship, etc.) movement...who are social entrepreneurs really serving? Are they serving others or are they serving themselves?

Anyway, I'm glad Tunde brought it up because I think he's right. At very least, social entrepreneurship can be an opiate for the middle class, and that possibility merits preventative action to ensure that social entrepreneurship (or other Social - X's) exist for reasons broader than being an opiate for the middle class.

What I think Tunde means by opiate is that it's an externally introduced activity that soothes the anxieties of the user and distracts them from the difficulties of their reality. Even more extreme, I think he means that the opiate of social entrepreneurship distracts the privileged from the full extent of the issues facing disadvantaged communities. I'll let Tunde weigh in and will update this post with any remarks he adds. For now, this is the working definition of "opiate" I'll use throughout this post.

[Here's a placeholder for Tunde's response. I'll update this placeholder should be reply with any remarks.]

I have often questioned the intention of certain social entrepreneurs, especially those widely publicized in mass-media publications. There's something about the air of those folks which is arrogant and condescending instead of inquisitive and humble. Moreover, some of the innovations presented by social entrepreneurs seem to be surprisingly self interested or misaligned with the real, palpable needs that the intended "customer" actually needs. Here's an example of a misaligned need - as told through a recount of why Bill Gates is less than amused by Google's (and others') attempts to provide internet access to the global poor.

It is this behavior - serving yourself more than serving others - that I see as the hat tip for social entrepreneurship as an opiate. This is because not serving a customer's need shows that you're interested in soothing yourself than serving another. Maybe Social Entrepreneurs are interested in looking cool (which is entirely possible when you're looking to get press to satiate a high-profile funder, rather than depending on a customer's payment to perpetuate your existence). Maybe social entrepreneurs hate their corporate job and hope social impact will alleviate their need to do something meaningful or interesting with their time. Maybe they're just curious people who think social entrepreneurship will allow them to travel to interesting places across the globe. The reason for "opiating" themselves - if that's what they are doing - could be anything. It's certainly possible.

What's more important is that this "opiating" I've described is presumably harmful. Like I said before, the processes of selfish social entrepreneurship could distract from real, needed social interventions by conveying the perception that the needy are being served. Perhaps more importantly though, is the chance that the growth of social entrepreneurship is a symptom not of social injustice but the disengagement of most workers from more traditional forms of employment.

Let me explain. In some senses, social entrepreneurship could be an opiate because it makes social entrepreneurs feel good and/or helps distract them from the fact that high-minded social interventions are all that matters in improving social outcomes for the world's most disadvantaged. But the "opiate effect" could also be people trying to make up for the fact that they hate their jobs and feel disengaged from them. (Note, I don't think disengagement is a good metric, but it's the most easily accessible to make this point right now.)

I'd like to note, I'm not suggesting that all social entrepreneurs are selfish, and self-aggrandizing. I'm merely suggesting that it's very reasonable to think that social entrepreneurs use their craft as an opiate. Moreover, I'm suggesting that because there's a clear path to using social entrepreneurship as an opiate, and that using social entrepreneurship as an opiate might indicate a presence of harm, we should be intentional about alleviating that harm.

I think there's at least one simple way to prevent social entrepreneurship from becoming an opiate for the middle classes: have real, authentic experiences inform efforts to pursue social entrepreneurship. In my limited forays to deeply understand social ills, I've found that - by experiencing the "front-lines" - it's not only informative, it's also humbling. Without understanding real, front-line needs, it's very easy to have a ivory-tower-esque solutions which are well received at cocktail parties (and well intentioned) by those who have no idea what's really going on in the lives of real people. That's where the disingenuousness fixes itself - by trying to understand the issues of real people (being "close to the customer", if you will) it's much easier to take effective, authentic intervening action.

Here's the rub, though.

The larger, and I suspect more transformational, opportunity to improving both employee and societal welfare is to give people ways of making an impact in their corporate jobs. That's why my focus is starting to shift from social entrepreneurship to social intrapreneurship. Through social intrapreneurship you have more resources to do good and you can generate more social returns that way. It's just not as sexy to talk about.

---

But enough of my opinion, what do you think? Does anyone even reject the premise of the question? I'd love to hear what you think.

My Race, In My America

Before this post, a statement:I've grappled with my racial identity, especially because I'm the first person from either side of my family to be born outside of India, my whole life. I'd like to share some of that reflection.

I'm fully aware that this is somewhat narcissistic and that race is a caustic subject. With that in mind, I'd like to qualify this post by saying that I will try to avoid making accusatory statements or speaking in platitudes about race in America. This post is about my experience. I know that my experience is but one of the many entirely unique perspectives on race.

I'm also qualifying this post because I'm tense about backlash. After all, I am recruiting for internships and future employers or business partners may not take too kindly to someone who is so "controversial." Perhaps though, that's exactly why I am writing this...because I feel like I have enough built up rapport to be able to withstand any social consequences which may arise. Not everyone has that luxury. I'm often naive about how my ideas will be received, I hope this isn't one of those times.

What all that said, if you have a thoughtful comment please do post it. I'd love to hear criticism of my perspective, for one. But also, I feel like if there are thoughtful comments it will do two things. First, it will demonstrate - in a small way - that it's possible, in America, to have nuanced, civil discourse about sensitive subjects. Second, it legitimizes this blog post, which will make me feel less vulnerable to social consequences. I admit that the second reason is selfish.

-Neil

And now the post.

---

"My Race"

There is no greater identity that has shaped my life than that of my "race." I use quotation marks here to make a point - that race is a social construct. Unfortunately though, it's a construct that feels real, daily. First, a bit about my racial identity.

I categorize myself as an Indian-American. I was born in the late eighties and I was the first person on either side of my family to be born outside of India. My parents, who I love dearly, are immigrants from Madhya Pradesh, a state in the heart of the country. Almost my entire family still resides there. I call my cousins brothers and sisters and most people think this is peculiar at first listen.

Race has colored my life in many ways, but it all comes down to one notion: I don't feel like I belong anywhere. I like hip-hop, but I was brought up speaking Hindi. I am decently good at math but I deferred a career in engineering or medicine. The values of my family make me relate more to practicing Christians than to Bollywood, even though I haven't been baptized and I don't take communion at Catholic Mass. I could continue with more examples, but the point is I'm always somewhat on the outside of a demographic group. I don't quite fit in, for one reason or another. There is never a time where I can comfortably fade into the background of a social setting. There's always something about me that sticks out, and it's often my race.

"My America"

Before I was born, there were lots of efforts to prevent institutional racism in America. Suffrage was greatly expanded. The poll tax was eliminated. The Civil Rights Act was passed. Diversity was written into Supreme Court jurisprudence as a compelling state interest in higher education. The list goes on.

But I still have the lingering feeling that America is too quickly trying to forget about it's race-riddled past. Changing policies is one thing, but changing hearts and minds is entirely another. On this point, here are a few examples illustrating when I've felt tremendously like a minority.

I grew up in Rochester, MI. It's a good town with generally good people. I went to good schools and lived a good life, I won't contest that. After I went to college though, I started noticing things when I returned to Rochester over Christmas vacations. People looked at me differently in public places than they did in Ann Arbor and seemed to be more guarded around me than they were my white friends. Once a woman with a baby brushed by me rudely as I held a door for her at a Thai restaurant. As her husband walked by, he whispered to me, "I'm sorry."

It was the first time I realized the gravity of what being a minority in America was. Yes, I suppose that woman could have been rude to me for any number of reasons and that her husband could have apologized for any number of other reasons. But for my white friends who are currently perplexed at my propensity to "play the race card," know that you begin to develop a "race radar" when you're a minority. You start to be able to decipher when people are treating you differently because of your race and when they aren't. I can't explain it. It's just an intuition that develops over time.

To underscore this point, I can't remember the number of times that people have talked to me like I don't understand English or change their tone of voice when I'm ordering a meal, relative to when my white dinner partners are. It often disgusts me how cashiers behave toward my father - who has a thick accent, still, but is one of the most educated people I know. My mother, who owns a small retail shipping business, has been slandered by angry customers who call her a foreigner and say that she "doesn't belong in this country."

To be fair, some of my mothers customers have defended her in the face of bigotry, and I don't have enough love in my heart to give to those folks. But based on my experiences, it's laughable to think that America is a "post-racial" society.

One final story, and a conclusion

The most recent instance of really feeling my race was at at a previous job. As a bit of context, know that Asian cultures are often more deferential to authority figures, like supervisors. American companies expect more upward management and expect that employees are more outward with their opinions and more aggressive about managing their careers.

I received an invitation to a webinar for Asian employees. It was a straight-talk panel in which more senior Asian managers would talk about how they managed their careers. The description of the webinar indicated that the panel would be giving tips on how Asian employees could learn to speak up and adapt to the culture of the company. This was fine advice, but to me it sent the signal that there was something wrong with me and that I had to change something about my nature/demeanor to be more successful at the company. What I've never seen in the corporate setting is a webinar for white managers to give them insights on how to better adapt their styles to get more out of Asian employees. The responsibility to fit in lies with the minority.

The company, is actually quite progressive with regard to diversity and inclusion, and this instance is only a subtlety. But it's powerful one. It's examples like this - that pervaded my experience growing up in America - that signal to me that there's something wrong with me as a minority. That's it's my responsibility to assimilate. That I have to choose between being who I am and having a healthy and prosperous life. That there are bounds on the type of person I'm allowed to be.

This is the most insidious aspect of race, because it subversively shapes the narrative you can create for your own life. Yes, it's not overt and it's not institutional but this shackle is just as powerful. It's a like a poll tax on your own psyche. And, yes, all the victories of the 20th century were instrumental for making America more equal. But the way I see it, and the way I feel personally is that I'm living with an unshakable feeling that there's something wrong with me because I'm not white. I feel like I'll never be able to be part of the club, because of the implicit attitudes of the country we live in.

Then I realize how lucky I am because of the family I was born into. And then I realize how hard it must be for minority citizens who didn't have as much of a head start as I did. It's a peculiar confluence of feelings.

Finally, let's assume for a second that we've made every institutional change that we need to make to ensure a fair and equal society. My gut tells me this isn't true, but let's assume it. Under this assumption then, I propose we set our sights on the next challenge of changing narratives about race, instead of claiming that race isn't really an issue in America anymore.

How might we ensure that every person in America doesn't feel like the possibilities of their own life aren't constrained by who they were born as? How can we help people change the narratives they create for themselves, for the better?

How "core" must social intrapreneurship be?

I came across this article today from Bill Eggers of Deloitte. The article gives several examples which suggest that true social innovation / intrapreneurship occurs when a business adapts one of its core activities to provide social good. This is in stark contrast to traditional CSR which takes ancillary activities or resources and directs them for social good. For example, a core activity is Wal-Mart greening its supply chain. A periphery activity would be Wal-Mart employees mobilizing a company-wide clothing drive to make donations to local charities. See how one is part of regular operations and one is a supplemental activity?

I kind of think that the sort of change we should be after needs to be as close to the "core" business as possible. So that a business is simultaneously creating economic and social value...rather than creating economic value, feeling guilty, and then doing something social to make up for it.

I don't see a moral distinction, and I think it's cool if business wants to make an impact by having its employees volunteer or donate stuff. And, for what it's worth, skills-based volunteerism seems to be somewhat "core" because of the learning gains employees receive.

It just seems like the non-core scenario, where a business directs ancillary activities and resources, is a lot of work. If you have a core activity (that's profitable) contribute to social good that might be harder to think up, but must easier to sustain indefinitely.

Influenza and the government blues

Yesterday, my mother called me to tell me that three young people died from influenza in Southeast Michigan. Worried about my health, she urged me to get a flu shot. I was probably more scornful than I should've been (at least in my own head) at my mom equating the death of three young people into a worry to call me at 11pm to get something that I thought "wasn't necessary." I decided to take a break from my accounting homework, of course, to look into flu shots and whether they were actually important. I started googling and found my way to CDC.gov, the website of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, a government agency. I started reading and was skeptical at first. After all, I thought, this is a government agency. Can I really trust the CDC?

And then it hit me. I was starting to let anti-government hype lead me to make bad decisions.

The CDC is the worldwide authority on disease control. They are, in my view, the most reputable source on whether I should get a flu shot. I forgot this for a moment because I was influenced by anti-government politicking and the foul-ups of the Obamacare website. Because of government's perceived inadequacies - that are widely publicized with manipulative PR spin - I had the slightest bit of doubt about the reliability of government information.

This paranoid skepticism of government information - about science and health, no less - is dangerous because flu shots are indeed really important. As it turns out, getting a flu shot is a big deal because it prevents you from getting the flu and it prevents the flu from spreading. This is especially important this year because H1N1 is a particularly virulent strain of the virus and hits young people especially hard - because we haven't gained immunity in previous outbreaks. The list of reasons is very convincing.

Part of the reason we're so skeptical of government is because of how politicized government can be and the shenanigans that can happen in Washington. Maybe the head of the CDC used to run a company that makes flu shots, I thought. I further pontificated that the CDC didn't have the money for accurate research or that its website hadn't been updated in awhile. I had all these doubts about government because a lot of what we see publicly is government failure, even though a lot of time government makes the right call. When I worked at the State Department, I was quite impressed with the level of competence of many Federal workers.

Surely, we should expect a government that is competent enough for us to trust to serve the public interest. Surely we should also expect better from the government we have - government does make mistakes on things that are really important. But I don't think this will happen by us (or talking heads) chiding that government do better, cutting funding irreverently, and expecting government to just improve. It's not just government's responsibility to "get their act together."

It's also on us, as citizens, to participate in government.

The way I see it, lots of things get messed up in government because public stops playing its role as a gadfly (like my homeboy Socrates). We have to attend public meetings, vote, and write letters. We need to donate to political campaigns. We need to support candidates who want to run government in a way that's in the public interest, not just in the pockets of special interests. We have to read and make our own decisions about policies, instead of depending solely on our particular flavor of hyper-polarized political pundit.

In my view, citizens participating is the surest way to a better functioning government.

I don't think this notion is exclusive to government, I think it applies to all institutions - from families to Fortune 500s. If a company is ineffective or doing ethically dubious things, employees need to speak up. If a non-profit is highly ineffective, fill out a feedback card. Providing honest feedback and following-up is how institutions improve.

Of course, I'm not suggesting we should blindly follow institutions - like government or business - and trust their words and actions irrationally. What I am suggesting, however, is that we should want institutions that we can trust and that it's partly our responsibility. If we want a government that we can trust, we should make it our business to regularly participate in the activities of that government.

I'm also suggesting that it's a good idea to consult with the CDC's guidelines and your doctor regarding flu shots!

Bow Ties, Crazy Socks, and Hip-Hop: Tactics For Successful Intrapreneurship

On the eve of my first lecture in my most anticipated winter term Course - Social Intrapreneurship - I wanted to think about my experiences as a social intrapreneur. (For more discussion of intrapreneurs, please see a post I penned a few weeks ago about the importance of cultivating intrapreneurs in Detroit). I've learned a few things along the way on how to be a successful (social) intrapreneur when I was working at a fairly conservative Big 4 Consulting firm. I'll try to break some of them down here. [See postscript for info on two of my intrapreneurial experiences]. Some tactics are similar to points raised in our first lecture's required reading. I wish I could take credit for having these thoughts first!:

Bow ties, crazy socks, and hip-hop I have a penchant for wearing slightly ostentatious clothing on a semi-regular basis. Right now, for example, I'm wearing socks that look like hamburgers. At work, I would also wear bow-ties and slip hip-hop colloquialisms into discussions with colleagues. At business school I'm not shy about carrying my Yelp lunch box either (it's really cool).

It's helpful to do this because pushing little organizational or social boundaries adds up. After a while, you earn permission to bend larger rules and do things that are increasingly unorthodox. You get known as the "creative guy" or the "gutsy guy", which makes it easier for people to trust you as you mobilize an initiative that seems to buck the company's normal culture.

Do it on the cheap It's very hard for a manager or executive to say no to an idea that's cheap. So, if you're trying something new don't ask for much money, if at all. Also, try to get people to volunteer their time to help you. By doing this it not only allows you to stay under the radar, it validates that other people actually support what you're doing. Moreover, forcing yourself to a $500 or even $50 budget makes you think cleverly and creatively about how to maximize the impact of your resource endowment.

Don't coerce people to be on your team When going out and doing something crazy and/or foolish, it's a pretty natural instinct to try sweet-talking people into helping you. I actually think this is a terrible idea, especially at the beginning. If you misrepresent what you are doing - or over promise rewards - you'll end up attracting people who are not truly committed to your cause. This is exactly what you DON'T want because early on in an unorthodox initiative you need people around you who are committed to seeing something to completion, even if it has some reputational cost in the short-term.

Instead, tell people the truth and find people who are passionate about what you're doing and give them assurance that they can leave your team when they want to. In my experience, those passionate people are the ones who stick with you through thick and thin...because they care about making an impact not, what they'll get out of joining your team.

That being said, take care of your teammates, make sure they get the type of reward/recognition they wish.

Be consistent and take the long view Intrapreneurship, especially social intrapreneurship, seems to follow an S-curve. It takes a long time to get going and reach a critical mass of influence or people. Then, it takes off and you can make big gains. Then, it tapers off as your innovation becomes adopted and goes mainstream. This is to say that intrapreneurship takes time (it's very difficult, but very rewarding).

For that reason, it's really important to pick a cause that you're willing to stick with consistently for a long time. The old adage applies here: think of intrapreneurship as a marathon and not a sprint. Moreover, I suspect successful intrapreneurs stick with their companies for a long time. After all, intrapreneurship takes coalition-building and that's very difficult to do if you're jumping from company to company.

Beware of bullies / seek out anti-bullies In my time, I've come across a few bullies who make it tough to be an intrapreneur. They are the types that manipulate situations to get what they want. They like control and care more about their personal advancement and definitely do not care about broader concerns like social impact. Working with these people is hard, because they guard resources and influence closely. I'd say try to never owe them any big favors, and, get strong allies to counteract their power over you. Even if the bullies are powerful in your organization, be wary of trusting them. Certainly don't trust them blindly.

At the same time, be watchful for "anti-bullies." These are the sort of people who care about advancing in the company, but also care about broader concerns. Many times these people are motivated by more than their paycheck or promotion schedule. These leaders truly care about transforming the company or the community. Help these people first, then worry about making sure they know you. Don't "network" with them, ally with them and help them. They will help you when they are ready.

Don't be shy about your passion Communicating passion is essential for two reasons. First, communicating your passion will make it easier for like-minded people to find you across organizational boundaries. They will hear about your passion and someone will introduce them to you, if they trust that your passion is authentic. Second, nobody will follow you unless you're willing to stand for something and take a risk. So, don't be shy. Speak up (without being insincere or obnoxious). There are lots of ways to communicate passion too, especially as social software percolates across large enterprises.

As a sub-point to this broader point, join cross-functional initiatives so you can get to know people across your organization. It becomes easier to do something intrapreneurial if you have networks and knowledge across your company.

Be good at your job The better you are at your job the more people will think you are competent and trust you when you do something different. You'll also have more leverage in negotiations if you're an indispensable employee. More than that, if you advance in your job you'll have bigger and bigger platforms to advance your intrapreneurial agenda. So do your job well. Really well.

----------

Here's a bit about two intrapreneurial initiatives I worked on in my previous job. (Yes, I bring these up to establish a modicum of credibility on this topic):

1 - I co-founded a pilot initiative to bolster skills-based volunteer initiatives at the conclusion of a seminar a team I was on gave about skills-based volunteerism and pro-bono work. We launched a pilot program to pair non-profits with volunteers, and provided tools and coaching so that the pairs could build a plan for a skills-based volunteer project. The idea was that if there was some infrastructure to help non-profits plan a solid project, it would be easier to attract volunteers. The initiative continues today.

2 - I worked on a cross-functional team to have a once-a-quarter event where two members of the office would give a short talk on a topic of passion or interest. At the first event, for example, one of my colleagues gave a 5 minute talk about his experiences training as a world-class pairs figure skater. It was just a way to build camaraderie and the program still continues today, as well. It was the first event of its kind across our office and presumably across all US offices of my firm.

What Business School Hasn't Taught Me

After reading a reflective and inspiring post from one of my friends and classmates about what 4 months of business school has taught her, I found myself doing the opposite. Instead of reflecting on what I've learned, I've been reflecting on what I haven't learned. For what it's worth, I'm not necessarily expecting to learn these things in business school, I merely catalog them here as a way of encouraging myself to learn these things on my own. Here are the three biggest gaps I can think of:

1. Structuring Unstructured Problems

Something that has been surprising about business school is that most of the business problems we study are already neatly summarized - whether it be in the cases we read or in the projects that are outlined by clubs who sponsor consulting projects. What I've found to be excruciatingly hard in my professional life (whether it be at work or volunteering) is that the most difficult part of any project is getting it off the ground and defining what it should be. This is precisely the exercise that business school eliminates from the problem solving process in cases, community consulting projects, or other challenges.

Defining problems takes a keen mind, discipline, experience, and many other strategies and attributes. It's hard to do generally, and even harder to do quickly, effectively, and cheaply. This is one of the things on my list that I would've expected business schools to emphasize. Instead of learning to "deal with ambiguity," we're learning to deal with ambiguity in predefined contexts and archetypes.

2. Understanding he responsibility that comes with the education provided by a top 10 business school

At my school, and presumably other top 10 schools, we're not strangers to the fact that we're going to a world-renowned business school. I've heard more than once, for example, that we're in the top .1% of all students studying management worldwide. Our institution implies that we are being groomed to be some of the world's most capable business leaders.

But what is the responsibility that comes with the purported power than many of us will have to influence the study and practice of management? Do we have obligations to advocate for fairness and responsibility? Must we think at all about the health of an industry and do we ever need to put the needs of that industry or the needs of society before that of the firms we are stewarding? What are the virtues we must exude as business leaders?

Sure, we have to take one required ethics or business law class, but this response seems to have a base rate bias. If ethics and responsibility matter more when you have power, shouldn't ethics and responsibility be more core to our academic experience than having a single class about it? Not to sound tired with a comic book cliche, but doesn't great power - that we will supposedly have - come with great responsibility?

3. Raising the ability of those who have not cultivated their own talents

One of the very strong realities which was tough to understand when I started working is that different people in the "real world" have different skills and abilities*. Not everyone has the had the opportunity to cultivate their talents as much as others. Consequently, some people aren't as capable as others.

In college, and even high school, I was surrounded by extremely talented people - this is a consequence of having privilege, I get that. But that's not what every organization and every team is like. Talent is spread disproportionately across our companies, institutions, and society, which means that some teams don't have very much talent. The chance that I'll be surrounded with an all-star team for every challenge I ever have is unlikely. Because of this reality, I think it's basically essential to learn how to help others raise their own abilities and cultivate their talents.

There doesn't seem to be any acknowledgment of this reality in business school. Even if it is acknowledged, this is something we don't really get the opportunity to learn about and deal with because we're not often around dysfunctional organizations. On the contrary, the organizations that the school chooses for us to work with on action-learning projects are handpicked so we can avoid dysfunction! In the instances where we work with dysfunctional organizations, presumably by accident, those stints only last a few weeks. This short time horizon makes it easy to work around problematic individuals, rather than work with them.

* - When I say this I don't imply that people are stuck being less talented than others, but that different people are at different stages of their own development. There also could be valid reasons that they are more or less talented in a given discipline, some reasons may even be outside their control.

Wrap up

Most of you reading this know that I attend the Ross School of Business. Most of you don't know that I've had a really difficult and interesting time adjusting to business school. I still think it's an exceptional school (with exceptional people, especially the faculty and staff). I present this merely as a way to reflect on my experiences thus far and hopefully improve upon them.

What's worse, however, is that I hardly think Ross is unique in this regard. From reading about and talking to people at other "top" business schools, the more I think the sorts of problems I suggest are endemic to business schools themselves. If that's the case, we either have to acknowledge my concerns as irrelevant, transform the pedagogy of management, or accept that the topics I've presented are things we business students have to learn on our own.

Though Undervalued Now, Intrapreneurs Are Essential To Detroit's Future

In Detroit, we celebrate entrepreneurs - whether they be social, civic, or for-profit entrepreneurs - and rightly so. Entrepreneurs create new technologies and possibilities in the markets they attempt to serve and disrupt. What is also true, however, is that entrepreneurs are scrappy. Their resources are often limited, so it makes sense that successful entrepreneurs seem to have vision, ingenuity, creativity, drive, and a willingness to take risk - without these things, entrepreneurs would have no edge over incumbents because they certainly have less resources. Entrepreneurs make do and ultimately succeed with less resources than their corporate counterparts. In my mind, this is an oxymoron. Why are entrepreneurs the ones who change industries and social problems, even though they usually have less talent, money, or other resources?

The most obvious explanation is that entrepreneurs can work without the confining attributes of large, political, risk-averse organizations. Entrepreneurs don't have to cut through red tape like those in corporations do. Because they're freed from the confines of traditional organizations they have high "ROR" - or "return on resources." By this I mean, they have a lot of results, given the limited about of resources to which they have access.

But, imagine the value that would be created if the ROR of organizations with large amounts of resources were higher? A 10% ROR for a $1B company is much higher than that of a $1M company.

What's needed to accomplish an increasing ROR in large organizations is not entrepreneurs, but intrapreneurs. Intrapreneurship is not a well definied concept within society...yet. Here's a working definition:

A person within a large corporation who takes direct responsibility for turning an idea into a profitable finished product through assertive risk-taking and innovation.

These intrapreneurs might create new products or services to generate increased profits within a business. Or maybe an intrapreneur builds a new idea which increases the social impact of the organization. Maybe the intrapreneur changes the way a company works so that it's a happier, healthier, or more effective organization.

Much like the way countries can't always export their way out of recession, I don't think Detroit will become a more vibrant city if we only create entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurship can't wholly replace the city's existing employment opportunities and industries except in decades, maybe. Entrepreneurship takes too long and is very risky, to name a few reasons. More than that, we have a tremendous amount of talent and resources in our local companies. To let those resources atrophy and become obsolete would be a waste and lost opportunity.

Imagine: Detroit could be a hub of private sector and local government intraprenurship and lead the nation in such efforts. We have institutions, companies, and industries ripe for a fresh approach. We have a dire need to adapt to changing economic, social, and civic realities. We also have a history of tenacious work ethic and ingenuity.

Detroit could be home to the world's best intrapreneurs and we would be better for it.

The Detroit Bankruptcy Conversation Nobody Is Having + Ideas To Make City Government More Accountable

I had the privilege of seeing Detroit Emergency Manager Kevyn Orr give the keynote address of the Revitalization & Business Conference, which occurred last Friday at Michigan's Ross School of Business. Generally speaking, I was very impressed with Orr and his sharp intellect as well as his thorough understanding of the issues facing the city. What Mr. Orr didn't discuss, however, (nor is it something widely discussed in news coverage about the bankruptcy) is the need to keep local government accountable and responsive to citizens' needs. I intend to start that conversation in this post. Surely, part of the reason Detroit had to file for bankruptcy was an institutional failure. During the past few decades, nobody really raised a flag calling the actions of civic leaders into question...at least in a way which was strong enough to avert Detroit's financial disaster. Nobody was watching the evolution of City Council's policies closely enough to prevent malfeasance or corruption. Nobody fact-checked City Hall's promises or management practices to see if they were legitimate. And now, Detroit is in bankruptcy and nobody is having a conversation (it seems) about how we can better keep our institutions accountable and our local government responsive to citizen's needs. Let's start now.

The way I figure it, there are a few stakeholder groups which, when working together, can hold local government accountable and efficient: City Hall (the executive branch), City Council (the legislative branch), the public (the citizenry and NGOs), and the press (the fourth estate). The judicial branch also has a role to play, but I'm leaving them off because I know very little about the courts. Here are a few ideas for each stakeholder group on how they can help hold local government more accountable. By experimenting with and implementing such ideas, I believe we'll be less likely to have another meltdown in the City of Detroit. These ideas are brief concepts - teasers, if you will - to be used as a starting point.

Citizen Marketing Strategy (City Hall, City Council, Public)

Marketing strategies are very powerful things. In them, you analyze your customer, your own capabilities, and what other organizations are doing to serve that customer. Then, you segment the market (put customers into unique groups, basically), target a segment, then figure out how to provide a powerful benefit for that segment. The whole point of marketing strategy exercises are to understand a real need that a specific type of customer has and then provide a real benefit to that customer, and do this all with a lot of discipline and rigor.

I think we could stand to see this sort of thinking utilized by local government. Imagine if all stakeholders - City Hall, City Council, the public, and the press - worked together to put together a marketing strategy for the city's citizens. First, they'd understand broad needs. Then, they'd try to cluster folks into different groups of unique needs (e.g., tech entrepreneurs, unmarried yuppies, young families, low-income elderly, etc.). From there, you could create detailed personas of what each of those customer segments needed.

The way this would help with accountability is that government could focus on the targeted customer segments they were designing a product or service for. We, as the public, could force government officials to talk about who they are trying to benefit with each policy they create, and thus hold them accountable for results. In my opinion, it's very hard to see if local government is actually effective if they can operate in platitudes of serving the "public interest" broadly. Having targeted segments would make them dig into real customer needs and provide government an invaluable to way to focus their efforts when deploying products and services.

Open Data (City Hall, City Council, Public)

Many states and municipalities are making some of their data publicly available. By doing this, citizens can analyze the data to look at the "proof in the pudding" as to whether their municipal government is actually running with integrity and efficiency. As is often said in journalism, sunlight is the best disinfectant. Moreover, governments can engage citizens in understanding and solving problems if they make data available for analysis. It's a win-win for everyone - we have more accountability and a way for many great minds to be helping the City improve services to its citizens

City Council Clubs (Public)

I think it's pretty important for citizens to participate in public meetings because it allows them to get information and because it puts citizens in a position to scrutinize (or collaborate with) public servants. The problem is, it's a lot of work to go to a city council meeting every time. So, I proposed this idea on this blog a few weeks ago which basically works like this: citizens get a group of their friends together and take turns attending public meetings and reporting back to the group. That lowers the transaction costs of doing so and gives citizens a constant presence at public meetings.

Citizens' Corps (City Council, Public)

One of the ways to increase accountability is to involve citizens more intimately in the political process. I also saw this in the private sector working as a consultant. The idea is that if you have more citizens dialogue with legislators about ideas, the ideas will be more responsive to their needs. But how could you do this? You'd create what I call "a Citizens' Corps". It's akin to a "change agent network", from corporate transformation nomenclature.

Each City Council member would get a group of community leaders with diverse perspectives together from their ward, kind of a kitchen cabinet. Then, the City Council members would have informal meetings with this Corps to discuss city issues. Sometimes this might be a way for citizens to make their Council member answer to them. Other times, maybe the Council member needs feedback, vis-a-vis each Citizens' Corp member getting feedback form his/her affinity group or neighborhood. Still other times maybe the Council member needs to communicate a message to citizens via the word of mouth generated by the Citizens' Corps members.

Basically, this vehicle is a way to create a network of committed citizens who have informal influence in their respective social groups. This network can be used to create two-way dialogue between Council members and everyday citizens.

Detroit Government News Hub (Public, Press)

Obviously, the press play a critical role in holding local government accountable. The difficulty is, search costs for articles are often high for finding local government news, and, mundane topics/meetings are never covered. I propose creating a curated blog network of city affairs. It would work like this. The press would create a website that consolidates all quality news articles about city government. Each article would be tagged with subject matter, committee names, council members, and any other relevant metadata. This metadata would allow the archive of articles to be easily searchable. Moreover, readers of the blog could submit articles they find useful to the curator, making it easier for the curator to do his/her job. Finally, say an amateur blogger or videographer attends a meeting of some sort in the city. This person could do a quick write up and submit it to the curator for inclusion on the news hub.

This sort of idea would help citizens follow issues as they transpire and be alerted to relevant articles about city government. By having easily accessible information, citizens can help each other stay informed about local government and hopefully make better political decisions / become more politically active. More political activity on the part of citizens would lead to more accountability.

Issue Prioritization & Goal Setting (City Hall, City Council, Public)

Governments often have long lists of (unpublished) priorities every year. In the Federal Government, for example, it's hard to keep track of all the initiatives the President and Congress want to push through. Say though, that the President had a list of his top 20 priorities for the year with a scorecard for success on each issue. First of all, If this were the case the public could weigh in on what the priorities should be, which is a valuable exercise to occur publicly. Second of all, the public would then have a somewhat objective way of judging whether the public servant is accomplishing his goals.

I think we could do this at the municipal level, too. Both the Mayor and City Council should make a list of their top 10 priorities for each year and provide a rubric for measuring success. That priority sheet could be refined with public feedback, provided online. Then, the public could track progress throughout the year or over the course of a term. Having the priority sheet would help the public help government keep track of its priorities and accomplishments.

External Feedback (City Hall, City Council, Public)

Independence is at the core of accountability in public accounting. Basically, you get someone to audit you every year to make sure your company is not misrepresenting finances. Why not get a similar perspective from outside Detroit to provide an independent critique of management and operations in the City? That could be a great way to infuse our thinking with some fresh perspective.