When growth becomes an excuse

Why past transformation can quietly become permission to stop growing.

Riding someone else’s coattails is a form of corruption.

It’s a way to benefit from work I have not earned. And it’s tempting. It’s comfortable to let things ride for as long as I can, avoiding the difficult work of creativity, leadership, growth, and delivering the next valuable thing. It’s also a way to avoid the emotional toll of rejection, failure, or obscurity.

It’s even easier to ride our own coattails — to relive glory days, to navel-gaze at past successes and think, wow, look at how much I’ve grown.

When I do this, I let myself off the hook from looking ahead and continuing to grow, serve, and innovate. Surely I don’t have to create more for others or give more of myself. Surely I don’t need to treat others better — look at how much I’ve already given.

However tempting, riding our own coattails may be even more corrupt than riding those of others. We’re not only benefiting from something we haven’t earned; we’re lying to ourselves about it.

I’ve struggled with this lately. I’ve been trapped in reflection about the past decade of my life. I’ve grown, contributed, and sacrificed so much since my father died ten years ago.

But you can’t profit off the same album forever.

I still yell at my kids. I still do little about the needs of the poorest in my community. I still miss deadlines. I still try to replace faith with control. My cholesterol still hovers at the edge of elevated. I am still crabby with Robyn more often than she deserves.

The point is: I’m still unfinished.

I don’t have to be a perfectionist. But I also can’t justify staying as I am forever by pointing to how far I’ve come.

I’ve been in awe of my own growth — and rightly so. It truly has been a decade of transformation for our family.

But growth becomes corruption the moment it becomes an excuse. It’s time to move on.

The break is over.

I won’t ride my own coattails forever.

Fasting from harsh words

Peace — in our souls and in our communities — doesn’t come from just being nicer.

It comes from starving the parts of us that crave conflict.

Our sons follow the same pattern as their father — which is also the pattern of paupers, billionaires, gangsters, and warring neighbors. How conflict escalates is predictable.

And the beef always starts with words.

With our sons, it starts with teasing. Then harsher teasing. Then a shove or a hip check. Then a hockey stick to the back — sometimes literally. And then it ends with tears, an ice pack, and resentment that must be slowed down and resolved.

It is the same pattern with many homicides. It starts with disrespect at a party. One thing leads to another. And eventually, someone is dead.

And perhaps the same with nations. It starts with jabs in the press. Then it escalates.

This is the pattern, so much of the time.

So of course, what the Holy Father shared makes sense: if we want a more peaceful and loving world, we begin by abstaining from harsh and hurtful language. And for those of us who are brothers and sisters in faith, we can make space for grace by fasting from that endlessly hungry gremlin — the words from which all beefs begin.

This is indeed a very practical form of abstinence — whether we approach it secularly, as members of an interfaith community who care about peace in a pluralistic society, or specifically as Christians seeking repentance and renewal during Lent.

No matter our posture, it makes sense to abstain from the thing that starts a wildfire.

—

And I need this fast myself, in a very guttural and deep way. To contemplate this as a fast is precisely the point. Because part of me needs to starve.

There is a part of me that is angry — frustrated by what I cannot control. It is the part that is deeply wounded and inflamed by small irritants. It is the part that is addicted to aggression and conflict, because the anger distracts me from the worries and doubts I would rather avoid. This all-consuming part of me is often unseen, but heard by my children when I am having a bad day.

I need to starve it of harsh words.

Because harsh words are what give an angry, fearful, selfish appendage its nourishment and oxygen. It feeds on vindictive and cutting language and asks for more the more it burns.

Harsh words and the anger that spurs them are not something I merely need to moderate. These are not like a bottle of wine, to be enjoyed over two or three days. These are things I need to abstain from — so that the appendage shrinks, withers, and perhaps one day fades.

I do not know if I can do this. My inner monologue feels rigid, and harsh words are deeply reinforced in our culture. It even feels expected that national leaders swear casually and publicly. Harsh words are one of the only forms of catharsis I know that are not drinking or some other youthful foolishness. And if I’m being honest, I’ve dropped a screaming “damn it!” In front of my sons twice since I started drafted this post over nothing - once over crispy crown potatoes, and once over a snow brush. I really do not know if I can do this.

And if I can? Who will I be if this appendage shrinks? I may not know myself from a stranger without this angry appendage that has been attached to me since coming of age?

Will I be delicate? Weak? Exploited? Bored? I do not know what this fast might make me into. If the appendage withers, will anything be left?

We never really know. This is how transformation works.

First, we suffer and sacrifice — through fasting, grieving, contemplation, exercise, or simply listening more deeply. This makes space for grace and other mysterious psychological forces to do their work.

Then we wait, not knowing who we will become on the other side.

That is the point.

All transformation requires an act of faith. Whether we understand it mystically or secularly, we cannot have renewal without trust in what lies beyond our sacrifices.

If we want a changed self — or a changed world — we must believe there is something worth becoming on the other side.

Be the Brakeman

A short story about conflict resolution, and evolving as a coach.

I’ve known for a long time that solving my sons’ conflicts for them creates fragility. At some point, after all, I’ll be gone, and they’ll need to resolve conflict without me as their judge and jury.

For several years, I tried to facilitate their peacemaking in two ways: by prompting the “right” discussion, or by imposing my less-favored answer to the problem—nobody watches TV if you can’t agree.

Stepping in strongly was necessary for a time. They needed guidance on how to resolve conflict; they weren’t born with those skills. But if I kept playing broker of peace, I knew their relationship would stay fragile—dependent on my presence, my rulings, my leverage.

Now I’m better served—and so are they—if I play a different role: brakeman, not intermediary.

I can slow things down. I don’t have to direct the entire outcome. I don’t have to do all the talking. They already have some skills, because we’ve practiced.

My job now is to be the person who says, “Whoa. Let’s slow down.”

Just this weekend, a Valentine’s Day trade went badly. And for the first time, by accident really, I slowed it down instead of negotiating a truce. Over a few hours, with some help, they worked it out themselves.

This was growth all around, for them and for me

The real insight is simple: they can do more on their own, and they should—but first, someone has to slow the moment down long enough for thinking to happen. They can resolve much more independently if hearts aren’t already racing and there aren’t already tears and screaming.

Slow it down. Be the brakeman. That’s my new job. If I do that, everything else becomes easier for them, and they can keep practicing conflict resolution—with less and less supervision from me over time.

Eventually, they’ll be able to pump their own brakes. And then I can coach a more advanced skill: self-reflection, repair, and the ability to turn hard moments into opportunities to deepen trust.

This feels like the pattern of any good coach. You start with fundamentals. You teach them to mastery. Then you coach the same fundamentals one level deeper. The temptation is to get stagnant—to keep teaching yesterday’s lesson after your kids have already moved on.

But we can’t.

As they grow, we have to deepen our own mastery so we can deepen theirs. If we stop learning, they will too.

Would they stop for us?

We are feeble and reckless. But we have grown morally over the millennia. Would aliens passing through our solar system stop to engage our world?

Encountering another intelligent species from elsewhere in the universe is a problem for the distant future. Still, it is an instructive one for our time.

Imagine that we had the capacity for first contact—say, through faster-than-light travel. Our interstellar flagship passes near a distant world. The first question its crew would ask is simple: Do we want to stop?

If they had the luxury of choice, they would likely evaluate that civilization along two dimensions.

First: What is their intent? Do they seek cooperation and mutual enrichment, or exploitation and dominance?

Second: What is their capability? Do they actually possess the power to carry out their intentions—peaceful or otherwise?

A civilization that is hostile and capable would be dangerous. One that is peaceful but utterly incapable might not be worth engaging. Intent and capability, together, would shape our decision.

Of course, determining either would be extraordinarily difficult. Learning to assess an alien civilization might take centuries. But these questions are not merely hypothetical.

We may create an artificially intelligent, Earth-based species in our lifetimes. But long before AI takes on physical form, we will face the same dilemma: What are its intentions? And how powerfully can it impose its will?

Yet before worrying about how we evaluate others, a more uncomfortable question presents itself.

What about us?

If an extraterrestrial civilization were passing through our solar system, how would they assess humanity’s intent and capability? Given the choice, would they stop—or continue on their way?

When I look in the mirror, and consider the history of our species up to the present, here is what I see.

I see a civilization whose intent has long been fearful and exploitative, yet has slowly, unevenly, inched toward governing itself more justly. Our past includes conquest, slavery, genocide, and monopolistic corporations. Empires swallowed continents. Entire peoples were systematically pillaged or murdered. Private power frequently corrupted public life. It is arguable that all these are still part of our reality.

And yet, over centuries, something has shifted.

Large-scale territorial conquest has become less acceptable, even when it still occurs. International institutions intervene—imperfectly, but meaningfully. Economic power remains unequal, but counterweights exist: unions, industry associations, regulatory regimes, and cultural movements that attempt to restrain abuse.

History does not move in a straight line. Exploitation resurfaces in new forms. But over long periods, the trajectory seems to bend—slowly—toward cooperative enrichment rather than exploitation. Two steps forward, one step back.

That progress matters. It suggests that, in the long run, our species has shown some capacity for moral learning. We inherit exploitative systems, but we also attempt—however inconsistently—to reform them rather than let them expand.

Our capability, however, tells a different story.

We have not harnessed the energy of our own planet, let alone our sun. We cannot survive beyond Earth without elaborate life support. We are actively degrading the habitability of the only home we have. We do not fully understand our ecosystems, our biology, or even our own minds.

Technological power has grown faster than wisdom. We build tools whose consequences we cannot fully contain. From nuclear weapons to climate systems to algorithmic platforms, our inventions routinely outrun our ability to govern them.

We are both feeble and reckless.

If I were the captain of a spacefaring vessel, I might conclude that, whatever our intentions, humanity remains a relatively immature civilization—morally improving, yet operationally juvenile. I would probably keep moving. Why risk engagement with a species still learning how to manage itself?

And yet, I wonder what we might still offer.

Perhaps our stories would matter. Homer and Shakespeare, Whitman and Rowling, express something enduring about love, fear, identity, and loss. Even an advanced civilization might find in human literature a unique window into our shared experience of consciousness.

Perhaps our experience with diversity would be instructive. Earth’s extraordinary ecological and cultural variation has forced us—imperfectly—to negotiate difference. Managing pluralism is central to our history. It may not be universal across intelligent life.

Perhaps even our physical fragility is meaningful. We are short-lived creatures, acutely aware of mortality. “Life is short” is not a cliché for us; it is a through line of how we navigate reality. For a species that lives centuries, or never dies, our relationship to time and death might offer unexpected insight.

It is possible that artificial intelligence will become our first true encounter with another form of intelligence. It is also possible that, centuries from now, we will meet non-Terran life. In either case, the same questions will apply.

What are our intentions? And are we capable of living up to them?

These questions offer a kind of civilizational north star. If we can cultivate a shared commitment to enrichment rather than exploitation—and if we can build institutions and technologies capable of sustaining that commitment—we will not only prepare ourselves for first contact.

We will make life better, here and now, for the people who already call our sacred, fragile, beautiful planet home.

Love, Radical and Unrelenting

I have not experienced love like this.

After a three day work trip, I landed too late. I would have to wait another day to see my family, who had already gone up north for a weekend with friends.

It was too risky to drive four hours in the frigid cold only to arrive after midnight.

So I drove home, left my luggage in the car, slept until four, made a cup of tea, and was out the door by 4:25.

Everyone was eating breakfast when I arrived at the cottage, weary. I saw Robyn first, and as I fused into her shoulder it felt as if my soul was remembering her, rising with lightness upward from the soles of my feet.

I have felt this love of pure lightness before.

But then, I kneeled to greet my three oldest sons who were playing on the family room floor. And they hugged me with a type of love I’ve never experienced.

They vaulted onto me. Their love was urgent and rough. It was unbridled, given with no limitation. It was cut roughshod, reckless even.

This love they showed me, with all four of us tumbling over the carpet and squeezing our arms around each other, matched the pent up energy of a banshee. This love was not gentle. This love was like a waterfall that could not be dammed. It was like lightning. It was radical and unrelenting.

I have never experienced love like this, where none of us were holding anything back.

As I look back on this, I find great comfort and wisdom in the existence of this radical and unrelenting love. It teaches that love need not be patient and kind. It affirms that love can be this unrestrained.

You see this sometimes at the international arrivals lobby at airports. Families wait for their loved one to emerge from behind a closed door, maybe a soldier returning from a deployment, and they weep in each others arms without any regard for who is watching. They just pour everything they have, all at once.

Shouldn’t we love others like that? Our closest ones of course, but also everyone, especially the least of us? Shouldn’t we show love as if unchained, with a total disregard for self-editing? Isn’t it the pinnacle of love to be so unconditional that it’s relentless?

Love can be a form of lightness, lifting our souls from the earth. But it can come in the form of something radical and unrelenting. To experience both is to experience something perfect.

What Good Fathers Teach Without Saying

In the decade between my father’s funeral and Clarence’s, I relearned how to measure a life.

How I measure my life has changed over time:

“Do any girls like me like me?”

“Am I getting good grades?”

“How much can I bench press?”

“Did I get into Harvard?”

“Am I making the news?”

“How many books have I sold?”

“Do we have a vacation home?”

“Does my family love me?”

“How many people will show up to my funeral?”

Looking back, none of these were great measures. Though I’m glad to have at least become slightly less arrogant and vain over time. Measuring something as singular and precious as a life is elusive.

—

The past decade of my life was bookended by funerals of good men who were fathers. The first was for my own father. The second was for Clarence, who I met because we both became Catholics together as adults.

For Clarence, I just wanted to go. I didn’t know him for even two years, but I still felt drawn to be at his funeral. I was puzzled by this. Why do I want to be at the funeral of someone with whom I spent so little time?

I knew him long enough, I thought, to know he was a good man.

And it was the same for my father. People showed up because they knew he was a good man—or they knew me and my mom well enough to discern that he was, too.

I have come to think that it is foolish to evaluate a life. Who even has the information to fairly and comprehensively judge themselves? I’ll never know anywhere close to the full effects of my choices, or even the full honesty of my intent. If I can’t even judge my own life, how could I begin to judge anyone else?

Judgment—not of the law, but of a life—isn’t a role for a human being. It is the role of God, or nobody at all. Nothing but an omniscient being even has the richness of perspective to judge a life.

So how do we even try to “measure” our lives? It is a fool’s errand.

But if we were to try, the best measure I can come up with is not how many people show up at my funeral—but why.

Do they show up out of obligation? Or do they show up because they felt loved, listened to, respected—because their soul felt some morsel of peace and joy when I was with them?

—

There are many aspects of our lives my father would be happy to see: that Robyn and I have a strong marriage, and that we love his grandsons most of all.

But also, I think he would feel relief that a lesson he never spoke of—but was always teaching—finally sunk in:

Take care of your duties. Do right by others and by God. That is how to live.

For many years I measured my life in terms of lesser things.

It’s not all the vanities of my youth that mattered. It is this.

And further, the lesson—the real enlightenment—is to realize that we ought not even to measure. We ought to do our duties, take care of others, and do right by God not for the fruits we will reap, but for its own sake.

We do the work because we do the work.

This is the timeless wisdom Arjun learns in the Bhagavad Gita—that my father managed to teach me through deeds, not words—and that has finally sunk in, ten years after he went ahead.

How do we measure a life?

If we can pursue our duty—our dharma—without attachment to its fruits, that may be the best measure of all.

Paradoxically, the best measure may be if we can persist on a righteous path without needing to measure at all.

Joy comes at a terrible price

But all the work and suffering is worth it.

To experience joy is to experience something perfect.

But even joy comes at a price. Because to feel a truly sublime joy, even for a moment, requires two things of us: we must be fully present and fully open—emotionally and perhaps even spiritually. This takes inner work. That work can’t be priced in dollars, but it is surely costly.

Fully Present, Fully Open

Joy is a feeling of the present—and of the body. It’s not something that can be experienced in the mind alone.

To see what I mean, try this: imagine a time you experienced true joy—one of those full tingles of lightness, where your soul felt like it was rising through your body. Does it feel the same as a memory? Try imagining a future moment of joy. Can you? Joy outside its exact moment is hard to replicate, isn’t it?

The closest we can come is when our senses trick our bodies into believing we’re back in that moment. Like when we see an old photo with our family, or smell a spice that reminds us of what our mother made during the holidays. Or maybe it’s a sound or song—like the echo of a marching band—that makes us feel as free and enmeshed as we once did at an alma mater.

These things are like a tuning fork striking a resonant frequency, making everything nearby vibrate. But they’re only echoes. The real thing—real joy—only happens when our attention and our feet are in the same place and time.

But full presence isn’t enough for joy. We must also be fully open—of heart, of spirit. Joy, after all, needs a way in.

I think of it like the aperture of a camera lens, or the pupil of an eye. The pupil expands to let in more light when it’s dark. It happens automatically in the body. For the photographer, it’s a choice. If more light is needed, the aperture must be widened. I believe our hearts are similar. We have to be open enough for the light to enter.

This can be difficult because the border of our inner world is like a two-way tunnel. If we want joy to find its way in, we also have to let darker feelings—sadness, grief, fear, anger—and all their discomfort and ugliness find their way out. We can constrict our hearts to shield ourselves from that pain when darkness leaves, but doing so also seals the tunnel to joy. Openness is not selective; we can’t welcome light without also making space for the dark. We can’t have one without the other.

How do we become fully present and fully open? That’s exactly what makes joy such an elusive feeling. One path requires tremendous inner work—through self-expression, journaling, prayer, meditation, or any other spiritual or contemplative practice.

The alternative to that discipline is suffering. Whether it’s grief, loss, or injustice, suffering forces us to become more present and more open. It changes us, whether we want it to or not, by giving us new eyes. In that sense, suffering is a kind of shortcut to joy—but it comes with its own heavy toll. In reality, most of us walk both paths: the slow transformation of discipline, and discontinuous growth borne of pain.

It Comes at a Terrible Price

It’s a common cliché to say, “you can’t appreciate sunshine without the rain.” And that may be true. It’s cute when it’s written in calligraphy on a craft at a farmers market. But what I’m talking about goes deeper than a resetting of perspective.

Joy is harder than that.

It’s not just a trick of the mind or a lesson to learn. The work we must go through—and the suffering we endure—is not optional. It’s a precondition of joy. We have to let something in us be broken down. Or we have to endure years of reflection, effort, and spiritual labor to even be capable of joy.

But at least we have that as comfort. At least all this suffering and journaling and spiritual struggle might make something beautiful.

Next week marks ten years since my father passed unexpectedly from congestive heart failure. It gives me hope—and some encouragement—that if I had to endure something so painful, so unjust, it at least carved out space for a deeper experience of joy in being a father myself.

I endured nearly ten years of loneliness and desperation before I met Robyn. It gives me hope that if I had to wander for so long, there’s a deeper joy I now experience in marriage.

Joy is really hard. And it comes at a terrible price. Sometimes I need to remind myself of that—that it’s supposed to be hard. I have chosen joy, and it’s supposed to be nearly unbearably difficult.

I’m not in this for pleasure. I’m not in this for a fun life. I don’t care about once-in-a-lifetime experiences that are perfectly photographed and meticulously shared. I don’t care about extravagance or self-care. I’m not here for hedonism, or validation, or the gram, or whatever else. I’m not even here for meaning and impact.

I’m in this for joy. And I have paid a terrible price for it. But I wrote this post, I suppose, to remind myself that even though I have chosen to endure all this, it is for something beautiful.

Joy may be the only perfect thing we can obtain in this imperfect human life. It has come at a terrible price—but it has been, and will be, worth it. Even if, one day, all I have left in this world are the remnants of that joy in whatever remains of me—then still, it will have been worth it.

Joy comes at a terrible price, but it is worth it.

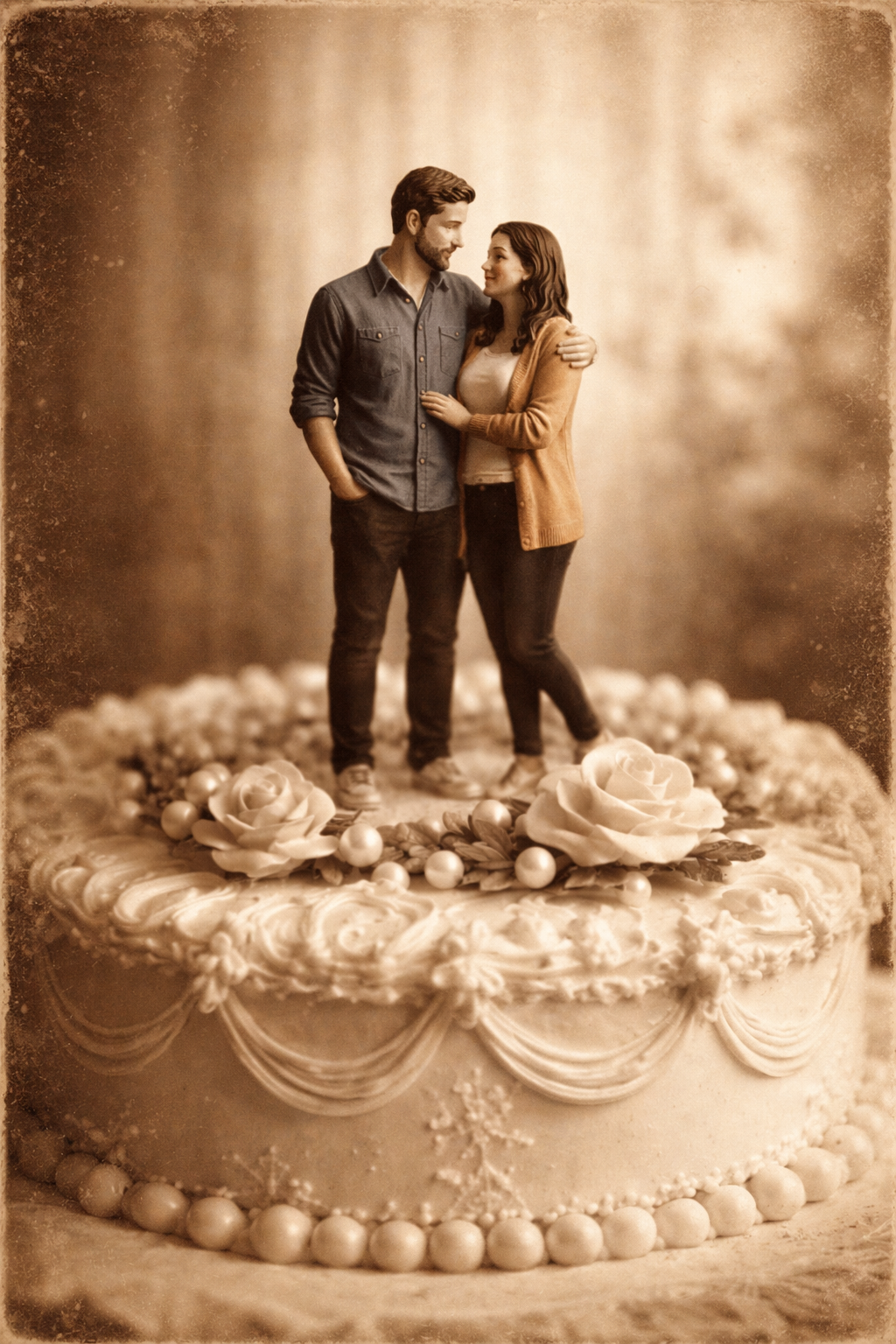

Life’s biggest decision: who you marry

Holding down a job is only a small part of a successful marriage.

Let’s stop pretending the biggest decision in life is what college you go to or what job you land. The real make-or-break decision? Who you marry.

In our family, this isn’t just a saying—it’s a foundational belief. Marriage isn’t one big day. It’s a lifelong choice that shapes your character, your children, your capacity to thrive, and your joy.

That means preparing our kids to answer four questions—really well:

Can they be a good spouse?

Do they act with integrity, love unconditionally, and make real sacrifices when it counts?Can they choose a good partner?

Do they know how to recognize integrity, unconditional love, and sacrificial character in someone else?Can they build a strong marriage?

When adversity hits, will they turn toward their partner instead of away—and grow stronger together?Can they support a family?

Can they generate enough income to meet their needs—and live with humble tastes, rather than chase status or excess?

Our entire education system is built around Question #4—economic self-sufficiency. Ironically, I’d argue it’s the least important trait when it comes to marrying well. So for the most important decision of their lives, our kids are left to learn from us, extended family, or maybe their friends—if they’re lucky.

That means the real curriculum—the one that actually shapes their future—is what we model and teach at home:

Things like integrity, love, and sacrifice. Like courage. Also self-awareness, discernment, communication, understanding, and leadership.

And yes—literacy. Because reading is how they’ll keep teaching themselves long after we’re done.

We do our kids a disservice in America because we act like holding down a job is the most important thing a person should be prepared to do. It’s not.

Believing that sells life short—and discounts the value of love, meaning, and human connection.

What we emphasize in America misses the point and leaves our kids unprepared to make the most important decision of their lives well.

“What did I learn this year?”

The question I’m contemplating heading into 2026.

This year was too hard not to learn from. What was the point if we didn’t get better from all this struggle?

This is what I learned. I hope that if you reflect on the year, you find some good learnings of your own.

—Neil

The healthcare system is desolate. The level of advocacy one needs to exert is unimaginable. So many doctors, bureaucrats, and complexities. It’s unbelievably difficult to piece together all the fragmented providers, payers, and incentives. If you don’t know someone—either to get you in somewhere or to help make sense of it—you’re at the mercy of a ruthless system. It’s not fair.

Kids are a paradox, not linear. On the one hand, they’re capable of tremendous growth and ability. On the other, they’re not ready to be adults. Calibrating exactly where they are—and how hard to push versus coach—is the most difficult aspect of parenting for me. This takes daily, perhaps even hourly, recalibration around where they are. I thought growth for children was linear and spiky. Somehow, it’s both.

I am not that patient. This was especially humbling—and a frequent realization—because I had a short fuse for an entire year. There was just too much in our orbit creating tension. I’m less patient than I thought. But at least I now understand that I’m relatively much more patient when I’m not rushing. The keystone behavior, for me at least, is pumping the brakes. If I’m slowing down, I at least have a fighting chance at patience.

A full life is chaotic. If I’m waiting for life to slow down, or for political administrations to change, or to just make it to the next break—it’s never going to happen. Not for any of us. The only way to have less chaos would be to unwind attachments to other people—whether it’s my wife, family, friends, kids, neighbors, colleagues, causes, ideas, or communities. I don’t really want that. Being part of this world means enmeshing yourself with others, and enmeshing yourself with others means subjecting yourself to chaos. We can’t make it stop, but we can draw a line for what we accept and what we don’t—what we’ll roll with and what we won’t.

I can’t do this without God in my corner. I’ve lived straddling domains of faith my whole life. I still have an unusual religious history and life. Spiritual exploration or religion isn’t for everyone—nor does it have to be. I tried for decades to keep spiritual growth at arm’s length. I just can’t anymore, nor do I want to.

And perhaps most importantly…

There are good people literally everywhere. This whole year, angels kept showing up. There are plenty of people who play their part in the game and facade of power, status, money, and dominance. There are plenty who treat their lives as a performance. Sure. But there are so many people who just live their lives, do their thing quietly, and try to do right by their neighbor. We don’t have to be part of the show if we don’t want to.

The Thief of Joy

In a world wired for comparison, I’m learning that joy isn’t found by avoiding it—but by choosing to start with presence.

One of my colleagues often reminds our team that “comparison is the thief of joy.” He’s right.

At work, we compare the software fixes we actually delivered versus the ideal. I compare myself to more professionally successful friends. I compare my tantrumming toddler to a calmer child—or even to a calmer version of himself. I may compare one colleague to a so-called “higher performer,” whatever that means.

A common kind of comparison many of us make—one that still steals from us—is comparing ourselves to someone less fortunate. “Appreciate the dinner you have; there are kids all over the world who are starving,” we might say to our picky-eating kids. But even this steals something—maybe our humanity—because to make the comparison, we must place ourselves above someone else.

All these comparisons steal joy.

But just as comparison is the thief of joy, it’s also the propellant of progress. To improve, comparison can be a useful tool and powerful motivator. We make change when we measure where we are against where we want to be or a competitor. Companies do this with financial statements. Patients do it with weight and body fat percentage. Our whole society is engineered to compare—and that leads to progress.

So we are in a bind, because two things at odds are true: comparison is the thief of joy, and also the propellant of progress.

Even if would rather it be otherwise, my brain is rigorously trained—yours may be too—to compare. I need a replacement behavior when I catch myself comparing. I can’t just “not compare.” I need to do something else instead.

It seems to me that the replacement behavior to train myself in is simply observing. Paying attention to what’s here, soaking it in, being present, meditating, noticing. These are all flavors of the same root behavior: observation.

We’re forced to compare our youngest son’s height and weight because he has been underweight his entire first year of life. I’m constantly fighting the urge to compare his milestones—crawling, sitting, teething—to children without Down syndrome. With him, the thief of joy is always near.

But so is the opportunity to observe and find joy. Griffin has a spark in his smile I can’t explain. He pulls me into observing him—soaking in the gift of who he is every time I see him. He is truly magnetic. And even though it’s so easy to slip into comparison with him, the joy he brings to my heart feels limitless. Because when I’m with him, I am fully there. Fully appreciating. Fully observing.

To me, this act—of observing long enough to outlast the temptation of comparison—feels like an act of defiance. That joy with Griffin feels like the most hard earned of all the joy we have in our lives. It is as much an act of desperation as it is an act of triumph.

I raise him skyward when I need to get back to the moment I am in. When I lift him above my head—he starts to lift his legs, and he smiles and giggles. And then I smile. And then I remember: he’s here. There is something to celebrate exactly in what he is. There is something unique and special in this lad. I don’t have to travel in my mind to an alternate time or an alternate universe where Griffin’s life wouldn’t be as hard as I know it’s going to be.

There is joy. Right here. Right now.

The way out of this bind is in the order of operations. We may not be able to function without comparison, but we can choose when we do it. The key is to start with observation. We can begin by soaking in what we have—by noticing assets and having gratitude. Then, after we’ve practiced observation, sure—we can compare.

So before I compare my kid to their calmer friend, I can observe their humor and sense of wonder. Before I compare my job to an easier one I could have, I can observe the chance I have to make a difference alongside amazing colleagues. I can observe the joy that’s already here—before I compare my life to what it could have been.

Comparison may be the thief of joy. But we can experience joy before we even open the door to that conniving thief.

My colleague reminded us that comparison is the thief of joy earlier this week because we had a software release. And at first, it ate at me. Because deep down, I have known this for a long time, but have been helpless to stop it. I know comparison steals my joy—and I’ve known it since I was a kid, when adults would compare me to other kids and the comparison would burn my childhood innocence.

But now, after reflecting more, I feel agency. And we should feel agency, rather than seeing comparison as an inevitability. Because even if we fall into the trap of comparison, we don’t have to start with it.

Our simplest, most beautiful, dreams

To love and be loved, to be free, to grow, to create, to have peace — these are the simplest of dreams. Nothing fancy, nothing complex — but still beautiful.

My brother shared the simplest but deepest gratitude at Thanksgiving dinner this year. He said he was grateful for traditions, because on days like Thanksgiving, many people have nowhere to go. He had people to spend time with, and many — including some he knows — do not.

This is perhaps the most basic of our dreams as human beings. It is so fundamental, it may also be an aspiration of many living creatures: that there are others you love, who love you back.

This is a dream, so simple, so elemental as to be forgettable. And yet, it moves us to tears when we realize it has become real. This is something I weep about weekly: the simplest, most universal dream in our world.

But there are more.

Another is freedom — to gather, to worship, to speak, to speak out.

Yet another is movement — to be healthy enough to walk around and go here and there.

There is the simple dream to grow — to learn, to read, to unlock the potential within us.

There is the dream to create — to make something, whether art, an idea, an invention, or a family — something good we can give or leave behind for others after we’re gone.

And finally, we dream of peace — to be whole, content, and in right relation with others, the natural world, and perhaps with God.

To love and be loved, to be free, to grow, to create, to have peace — these are the simplest of dreams. Nothing fancy, nothing complex — but still beautiful.

It does not surprise me that these are the things older people, who have had ample time to experience both joy and suffering, advise us to pursue. These are the dreams we all share, the ones that bind us, when life washes away lesser desires.

I think we miss the plot sometimes. I certainly do. We forget that what we value most is simple.

Instead, we so easily get wrapped up in the pursuit of complicated products, laws, policies, systems, and programs. We get obsessed with the minutiae of the world and forget how it ladders up to our simple, more grounded desires. AI is a convenient example of this. The world has gone mad with AI, seemingly for its own sake, rather than as a means to some more purposeful end.

To be sure, AI and other powerful ideas — like nuclear power, bioengineering, economic growth, and perhaps the idea of America itself — are important. But how often do those things get remembered in the context of love, daily freedoms, creativity, flourishing, or peace? We often lose the plot, distracted by the mystery, power, and shine. We squabble and lust over the most abstract of things and lose sight of the simple dreams we’re all after.

Whether in politics, business, civic life, family life, or communities of faith — we don’t have to chase and optimize that which is minute. We don’t need to get wrapped up in layer upon layer of abstraction within economy, technology, theology, or any other word that ends in “-y” or “-ism.”

This is what I love about the holidays, and especially Thanksgiving: we’re reminded of the simple things that matter most, the ones we so easily lose sight of. Even as we grow the economy, build better governments, and chase bold innovation, we mustn’t lose sight of the simple reasons why we do it all.

To love and be loved, to be free, to grow and flourish, to create, to have peace. These are the simplest, most beautiful, of dreams.

We can’t let these dreams be lost, and become afterthoughts of progress. All our striving, all our squabbling — it’s for these dreams.

Mercy, Unasked

There is a vibrancy and holiness that comes when we exchange in mercy.

Mercy

I have never asked for mercy once in my life—until today. Not from a person, and not in prayer. Not once. A surprisingly vivid memory from high school is a microcosm of why.

I was hanging out with a bunch of other guys from school in my friend’s basement—for our weekly post-school afternoon of the Nerf Combat League. (Yes, it was a real thing, and yes, it was awesome.) I can’t remember why, but I ended up wrestling someone. Which is surprising, even now, because I haven’t wrestled anyone before or since.

Obviously, I was pinned quickly. The guy wrestling me, Mike, kept saying, “Tap out, tap out!” And I didn’t—not until my trachea started to tighten and saliva dripped from my mouth.

Mike said something like, “You didn’t tap out. Respect.”

That’s what it’s like for a teenage boy—you take pride in not asking for mercy. Mercy is just not a currency you exchange in. It’s not that anyone is anti-mercy; it’s that the concept of mercy may as well not exist. If anything, you’re supposed to be the one powerful enough to grant mercy to someone else. And some even sadistically relish being the one who inflicts suffering, itching for the payoff of someone begging for a reprieve.

As awful as a world would be where no one shows mercy, I think it would be even colder—more dystopian—if no one even asked for it. Looking back, the fact that I can’t recall ever asking for mercy—in any situation—feels deeply warped.

—

Those who are truly holy and noble, I believe, are the ones who show mercy even when it’s not asked for.

Reflecting on this today, I realize I’ve certainly been the beneficiary of mercy I didn’t ask for. Because during this past year—the longest and hardest of our lives—angels have shown up. Constantly.

There have been friends who offered warmth. Family who bailed us out of binds. Colleagues whose dad jokes doubled me over with laughter. Neighbors who looked in on us. Other parents at the school or on our soccer team who have our back—and let us have theirs.

Mentors who guided me through a formation of faith and immense professional challenge. Even strangers in public who found ways to encourage me when I was solo with the kids at the grocery store. And perhaps most of all, there’s Griffin’s magnetic, earnest smile—a joy so pure, it feels divinely gifted.

These are two of the most important lessons of the year, and both are about mercy.

First: to ask for it. Such a simple lesson, yet so enigmatic.

And second: that there is mercy all around us that we never asked for.

To be that kind of person—an agent of mercy, whether sourced from God, from our soul, or from wherever you believe mercy comes—who offers it unasked…That, I believe, is the high watermark of holiness we can reach as mere mortals.

Originality is the only game left

As human artists, our last edge versus the computer is originality.

I will never beat the algorithm.

Practically none of us who create will — whether we’re writers, musicians, artists, filmmakers, actors, playwrights, acrobats, comedians, dancers, or anything else. I’m tired of trying.

I will never be more efficient than generative AI. I will never be able to buy enough digital ads to break through, nor will I ever be chosen by a publisher who vaults me to relevance. I will never be able to bullshit and write something I don’t believe just because I know people want to hear it.

Some say AI will ruin art and bankrupt creators. I’m actually excited for the effect AI will have on art and artists.

For us human beings, there’s only one play left in the playbook: be ourselves — our plain old original selves.

We can’t beat the computer on any other front. No one else, and no machine, can be us. The game is over, and it seems like the one remaining edge we have is to stop playing the game - of catering to the zeitgeist or waxing sensational - and be original.

What little leeway we had to optimize our way into an audience will vanish as AI-generated expression floods every medium and every distribution channel — cheaper and faster than any human artist.

But I think that’s liberating.

Why bother chameleoning who we are as artists if we can’t win doing that anyway? It’s better to just do our thing and create for the audience that values our thumbprint and voice.

I can only speak for myself — an amateur but extremely serious artist on the margins — but I’ve felt a kind of permission I’ve never felt before: to just let it rip. No more anxiety, self-editing, and asking my ChatGPT editor to reassure me of my chops as a writer. The new playbook is to listen deeply inward and just write.

So why not? I’ll never beat AI at its game — being more efficient, more personalized, and telling people what they want to hear — so why play? My guess is that anyone who sees themselves as an artist, rather than an entertainer, feels this at some level. If this is what the marginal artist feels, I think that’s great.

If those of us — like me — who feel the pressure to chase clicks just throw in the towel on beating AI, it might lead to the greatest wave of original work the world has seen in generations.

If AI has left us no choice but to be original, damn am I excited.

Psalm for Whispers

In a world full of screaming, creating quiet spaces is a small act of holiness.

“He got more chocolate chips than me! I don’t want to wear a belt! THAT’S NOT FAIR!”

In these moments? Lord help me. But what if my sons only scream because they have to?

Maybe it’s not them being young and emotionally immature. Maybe it’s because everywhere they ever are—even in the quietest rooms—there is always screaming.

The world has been full of loud machines for decades, but now they scream.

Machines that beg for you to use them, even when you don’t want to. Phones are the obvious one. The notifications aren’t just little red dots; they are screams for attention—trying to get you to interact with apps, or spam calls, or scrolling advertisements.

But it’s not just the phone anymore. Anything that is “smart” is clever enough to speak up and scream back at me—the lights, my tagged keys, even the air purifier screams for its filter to be replaced.

Even in the quietest of rooms, there is always screaming.

With the volume already up, businesses are screaming louder for attention so that we buy or sell or borrow or lend. Charities scream at us to donate and patronize. Politicians scream in their own ads, but also in the newscasts and posts that we watch freely. Even some faith leaders amp up what should be an inherently peaceful message—by screaming it instead of preaching it.

Even in my own head, there are screams that nobody else hears, but my children and wife see me suffering from them. The screams of the to-do list. The sink full of dishes. My job that’s never satisfied. My hungry stomach craving breakfast that I can only eat standing, as I make my big sons’ cheese sandwiches for their lunchboxes.

Do you ever hear the screams, too?

There is the screaming of the pages my heart desperately needs to write. Or my soul that yearns to hear the crunch of leaves and the songs of the trees at the park—anything to noise-cancel the screaming. There is the shower I need to take, my skin craving the feel of bar soap, warm water, and a shave.

Even in the quietest of rooms, there is always screaming.

And so of course our kids scream. To be heard, they have no other choice. The latent volume level of the world around us—with every object, person, and organization jockeying for attention—is screaming.

Maybe it’s not them that need to be quiet, but the screaming surrounding them that does.

Perhaps the most important new skill we need as parents in the early 21st century is the skill of turning the volume down—tuning the sound of all the screaming noise from a 10 to a 1.

The way we get our kids to stop screaming is by creating the equivalent of a library in a space we share with them. A place quiet enough—figuratively speaking—where they don’t have to scream. Where there is no competition for their voice. Where my ears, heart, mind, and soul can even hear when they whisper.

This is why prayer, meditation, journaling, simple walks in the woods, and other contemplative practices are so important. These are the ways we learn how to turn down the volume.

Yes, it is true—at least in the world we live in today—even in the quietest of rooms, there is always screaming.

But there are ways to turn down the volume.

And we owe it to those we love and who love us—especially our kids—to turn down the volume. So, with us at least, they don’t feel like their only option is to join in on the screaming.

Even if the world around us keeps screaming, we don’t have to let it stay loud. We can turn it down—until we can finally hear our children whisper.

A Mantra For Those Who Feel Squeezed

The only way this totally squeezed life works is if we help each other.

I think I’m at least 80% accepting of the fact, finally, that I won’t be a wealthy man. We’re blessed, and affluent by most standards, but our base budget is certainly humbled by the fact that we have four kids.

And this tension—between feeling like we’re making it but still feeling stretched—also exists with our time.

We show up for our kids and help out our family, friends, and neighbors as much as we can. But we also always feel like we’re drowning—the laundry, dishes, and daily grind are never stable. Despite the fact that we’d admit we’re doing our best and doing a decent job, it never feels like enough.

And despite all this, I still feel so much selfish guilt.

I don’t serve anyone in need whom I don’t already know, in any meaningful way, though my faith and my own moral sensibility demand it. I have let down friends—all the time, lately—it takes me months to call someone back or set up lunch, catch up over drinks, or deliver a meal to help out friends who are new parents.

We are part of the squeezed middle—we’re not living month to month with our money or time—but we don’t have enough time or money to easily trade one for the other. We’re squeezed.

And I don’t mean this as a “middle class” issue, per se, because there are plenty of families wealthier and poorer than ours, both in time and money, who feel squeezed. From investment bankers to blue-collar workers, I know families across the spectrum who feel this same pressure.

The squeezed are a surprisingly large cohort who feel stuck because they can’t trade time for money or money for time.

Leaving a Penny

I think the only way out of this is to help each other—even when it feels like no more than a penny’s worth. Little things matter. I’ve seen it in my own life.

There are a few families on our soccer team that carpool to practice. Freeing up one night per family, per week makes a difference. When other families at our school keep an eye out for our kids and we keep an eye out for theirs, it makes a difference. When someone comes with their pickup truck to help move some furniture, it makes a difference.

All these little things are like those old cups at grocery stores that said, “Have a penny, leave a penny. Need a penny, take a penny.” Little things that show up where you’re squeezed matter a great deal.

And something that feels small to us—like just giving a penny—can feel like receiving a gold coin to someone else.

For example, me shoveling my older neighbors’ snow barely registers as 20 minutes of extra work for me, but it’s unbelievably helpful to them so they aren’t beholden to unreliable help when they need their driveway clear to go to a doctor’s appointment.

Similarly, it felt very small to her when a good friend and neighbor came over to watch our kids for 20 minutes when Griffin was born and Robyn was conveyed by ambulance from the living room to the hospital—but to us, it was worth more than a bag of gold.

When we leave and take pennies, it relieves the squeeze. These little pennies are hardly worth just one cent—they’re often worth their weight in gold. “One cent” can feel like salvation when you’re being crushed.

I feel squeezed every single day of my life.

If I could afford to throw more money at problems, I would. But most of my problems wouldn’t get that much better with more money—grocery delivery doesn’t save me a trip because it’s never right, and I’d never be willing to outsource going to my sons’ soccer games, even if we could afford it.

And I’m unwilling to detach either. I’d rather live with the guilt of not meeting my commitments to my friends and people in need, rather than pretending like it doesn’t matter. Because it does. I don’t want to be less squeezed just for me, I want to also be there to stick up for those who have no penny to give.

I don’t think changing laws can help us, in the immediate anyway. I don’t think AI will save us either. The financial windfall that will allow me to gain hours of my time back is never going to come. And I’m tired of waiting for a hero to save me. We are the only heroes we’ll ever get.

The only way this works is if we help each other.

It’s good enough for it to be in small ways. These small acts of support are the only real alchemy I’ve ever seen work. Because when we leave a penny, it’s not one cent we’re leaving—we’re leaving something for someone else that’s worth its weight in gold.

So if you’re feeling squeezed, we need to stick together. Remember this mantra: take a penny, leave a penny. We are all we’ve got, and we are enough to get through this.

And We’re back at Hogwarts

We’ve started reading Harry Potter with our older two kids.

Seeing our older sons experience Harry Potter and the Sorceror’s Stone for the first time has been magical. Robyn finished the first book with them tonight.

Seeing the story through their reactions has made me see some timeless lesson in new ways. These are the best ones.

The story is powerful because we are part of it. We are dropped into the story as if we are joined to Harry somehow. It’s immersive and builds unquenchable intrigue. We feel like we’re there and desperately want it to be real.

For example - our oldest thinks maybe, just maybe, he will get a letter by owl inviting him to be a first year at Hogwarts. We learn how the events unfold as Harry does. Harry, Ron, and Hermione feel like they actually are our friends and we are part of Gryffindor house. Would the story inspire and resonate across generations if it was told at us, rather than feel like it was happening to us? No! I think this is why Star Wars also feels so timeless (and makes for a great theme park) we feel like part of it.

This is a lesson for any team we are trying to inspire - we have to make them feel like they’re part of it, and they have to also want it to be real.

There are great wizards from every house, and heroes in unlikely places. Sure, since Harry is the narrator, of course we’re going to hate Slytherin when we read it as children. But, we keep telling our sons - Gryffindor is not the only good house. If they are sorted into a house, with an online quiz or figuratively in life, they key is picking the environment that gets the greatness out of them, not just doing what they perceive is the only “good” answer.

Similarly, as readers we believe that Snape is awful and Neville is nice, but a sissy when we first meet them. Great strength and courage and kindness is often hidden, or, it takes the right circumstances for it to show itself. There are more heroes than just Harry, and there are more great houses than only Gryffindor.

There is no one right path. This is a lesson I need to be reminded about my own life and career - especially when I succumb and o comparing myself to my very esteemed colleagues and classmates.

And finally, I had forgotten and certainly didn’t realize the wisdom in Dumbledore’s speech at the end of term feast when I first picked up the book. Yes, it’s so true that it takes great bravery to stand up to our enemies but also, it takes great bravery to stand up to our friends. What a relevant lesson today, in the culture we live in, just as relevant as it was when The Sorcerer’s Stone was first released. How different might our world be if we stood up to our friends when their decisions were not in the right?

What a wonderful gift bringing the tales of Harry Potter back into our lives has been.

Why we all want to retire

Work is dreadful, by design.

It should not be a surprise that most people feel somewhere between indifference and dread about their jobs.

First, there’s power asymmetry by design. That means we should expect to be treated badly or exploited - because when one person is more powerful than another, this is what happens.

Second, that we are loved conditionally is expected. We are rewarded and praised if we achieve the result others want. And if not, we are ostracized or removed.

At work, these are normal things.

If we subject ourselves to power asymmetry and conditional love, shouldn’t we expect to dread it?

Unless our work situation is wildly different from the norm, it’d be crazy not to dread it.

Those “bad people” may surprise us

We don’t have to trust everyone — but we should stay open to being surprised.

I expected Jay to be guarded and callous, and at a minimum indifferent toward me — because that’s what our culture taught me to expect. But he wasn’t. Jay surprised me.

Jay — let’s call him that — has been a source of hope ever since, because when people surprise you, it shows that not everyone you’ve been taught to distrust truly deserves it.

He was on probation for a violent crime and only a few years younger than me. He was also a gunshot victim, attached to a catheter and urine bag because of his injuries. The cane he walked with was leaning against the table next to him.

I spent 20 or 30 minutes breaking bread with Jay nearly 10 years ago at a community event I attended while working as a civilian at the Detroit Police Department.

The first surprise was that he was even open to chatting when I sat down for dinner next to him. He was also so vibrant — hopeful, even. He said he had a child and wanted to find a way to provide for them, no matter what it took.

He had an unforgettable warmth and smile for anyone, let alone someone who had been through so much. Years later, I am still surprised by who he was, compared to who I expected him to be.

Whether we believe strangers are good people or bad people is of great consequence.

This is one of the most deeply embedded beliefs that poisons our culture in America, I think. We collectively believe everyone else — those not like us — must be bad, not to be trusted.

And what happens when we can’t trust those other people? We need weapons and protection from them. We need to lock them up. We need to build walls and ensure those evil people stay away.

And it’s easier to justify treating them with cruelty or exploitation — because hell, they’re bad people anyway.

In my life and travels, I’ve heard enough strangers’ stories to believe the opposite. In addition to Jay, there’s Gerry, whom I met at a bookstore — he moved to Detroit to pursue a dream of reducing shootings, and I still keep in touch with him. Everyone has something about them that is extraordinary, if we’re willing to listen.

I hope, at least, that everyone is open to the possibility that the person in front of them may surprise them — open enough to change their mind about someone they’ve been taught is untrustworthy.

Because when we do, maybe we don’t need all those weapons or walls to feel safe from all those people out there we’re so sure are bad. With an openness to surprise, we can actually work out our differences without simply trying to bully them and exert power until they submit.

I don’t think it’s our obligation to trust everyone. But to be trustworthy and work to be trustworthy? I think that’s the greatest gift we can give our great grandchildren — because a more trustworthy and trusting world requires fewer guns, less fighting, and less anger.

We can’t give up on the hope borne of surprise. We can’t give up on the hope that people we fear might turn out to be good.

Fill The Cup, Brother

In the end, the question isn’t whether the cup is half full or half empty — it’s whether we fill it.

Is the cup half full or half empty?

What a self-absorbed little riddle — as if a glass gives a damn about my optimism.

It’s one of those falsely profound clichés of self-awareness — the kind you toss out after you’ve already asked about the weather.

Because the truth is, the cup isn’t half anything. It’s just not full. All that talk about half full and half empty is just stalling — a way to avoid the work of actually filling it.

If there’s any question worth asking, it’s this: what fills the cup?

There’s the cheap stuff — the elixirs that vanish the second they hit the air: dominance, vanity, hedonism, booze.

Then there’s the good stuff — the richer elixir. Sacrifice. Eye contact. Service. Prayer. Creative expression. Movement. Nature. Reconciliation. These are the grounded things that squeeze juice from the fruits of love, justice, and light.

I often think about that reflection exercise — the one where you imagine yourself on your deathbed. Thinking about who’s there, and what we’d be thinking in that moment, helps clarify what might fill our cups now.

I tell myself this:

Feel the pain and suffering of your last illness. See the faces of your grown sons, your brothers, and your sisters. Feel Robyn squeezing your hand with hers.

In those moments, will waxing poetic about optimism or pessimism be what we want? No. Will we crave one more chance to assert dominance? No.

We’ll be clawing for one more chance at the good stuff. On our deathbeds, we’ll do everything we can to fill our cups a little more — cherishing every drop.

So why, right now, do we pretend those debates are worth having?

No amount of talk will change how much is in the cup or what elixir is in it.

Should we eat well, sleep well, and keep moving? Yes. Write once a week to keep ourselves sane? Sure. Do what we need to do to patch the holes in our own cups? Absolutely.

But damn.

Brother, don’t be fooled by all the people who talk like they’re too busy for their kids, who treat parenting like a chore. Don’t mimic those who drown themselves in work without setting boundaries, then draw an audience to complain about it. Don’t give up, settling for narcissism instead of agency.

Do none of that.

Fill the cup, brother.

No amount of talk will change how much is in the cup or what elixir is in it.

Every moment of every day, fill the cup. That’s what we do.

Real or Not, We Believe In Magic

Santa and Mickey aren’t real—but the magic they bring to life is.

This may be the year our oldest son, Robert, discovers the truth about Santa Claus.

The other day, he told Robyn that he thinks Mickey Mouse is just someone in a mouse costume. “Mickey isn’t real,” he said, with both pride at figuring it out and a touch of sadness for what it meant. And of course, Santa Claus is the next mythology he’s bound to question.

But aren’t Mickey and Santa real—because the magic they represent is real?

There was awe and wonder in the moment our family stood together watching the Fantasmic show and fireworks over Cinderella’s Castle. Robert, in a full measure of his three-year-old earnestness, looked up at us, his eyes gleaming in the dark, and said:

“I am the magic.”

We all felt it—our kids and us, as full-grown adults. That was magic, and it was real.

There is magic on Christmas morning, as there has been every year of my life, because it’s tradition. And when presents appear under the trees of families struggling to pay their bills—gifts from anonymous strangers—what else can we call it but magic?

Mickey Mouse and Santa Claus aren’t real in the same way George Washington or the Grand Canyon are real. They are symbols. They’ve only ever existed as symbols.

But the magic they create is real. The beliefs and ethos they carry are real. Maybe asking if they are real isn’t even the right question.

The better question is: do we believe?

Do we believe in what they represent?

Do we want to be part of the magic they create?

If so, does it really matter whether they are real or imagined?

And isn’t the same true for so many other things that aren’t tangible? For liberalism or capitalism—philosophies that only exist if people believe in them, yet have unlocked freedom and prosperity for billions? What about the fables and legends we pass down through generations, like our grandparents’ sacrifices in war—or even Star Wars? For God and faith traditions? For virtue and character?

Maybe these things are “real” like a rock is real, maybe not. Maybe as symbols they are real, maybe not.

What matters to me is the magic they create. That, if nothing else, is real.

So when my son asks me if Santa is “real,” I think I’ll tell him: Real is not the point. Real or not, I believe in Santa Claus, in Mickey Mouse, and in all the other beautiful, wonderful, magical things that make life meaningful.

And when I tell him that, I hope he realizes that even if it’s not real, it’s okay to believe in magic. And maybe one day, he’ll share the same thing to his own kid.